Four generations strong, the Mahlase family has welcomed many babies into the world. And while each new arrival has been an occasion for joy, one major factor has differentiated them: some of the births officially happened, and some, as far as the government knows, did not.

This disparity reflects a changing South Africa. Early on, some black South Africans didn’t register their children’s births because the bureaucratic process seemed irrelevant to their lives. Later, during Apartheid, this same bureaucracy became all too relevant — common civil records were used by the regime to codify discrimination. Flying under the radar became a survival tactic.

But since Apartheid ended, South Africa has done something remarkable. It has achieved near-universal birth registration, and has transformed the lives of millions in the process. Getting 95 percent of its citizens registered was no small feat in a country where birth records were once used as a tool to oppress an entire race. How they did it is a story worth telling.

One family, many experiences

Gogo Mahlase never considered registering the births of her children. She gave birth at home in the 1960s with the assistance of midwives, a common experience for black women at the time. Gogo had little interaction with the government; to her, civic processes like birth registration were a distant abstraction. When her children tried to acquire identity documents later in life, the only reason Gogo knew their birth dates was because her Catholic parish still had their baptism records.

Fast forward to the 1990s. Gogo’s son, Justice Mahlase, had a very different experience than his mother, and in fact, saw the registration process change across the years of his three children’s births. By the time he had his first child it was standard practice to give birth in a medical setting. His first was born in a rural clinic in 1990, where access to social services was limited. Mr. Mahlase had to make a real effort to register the child’s birth with the relevant officials.

When it came to his second, third and fourth children — born in hospitals in 1992, 1997 and 2005 — Justice found the registration process becoming easier with each birth. Likewise, when one of those four children was ready to give birth themselves a couple decades later, she did it right there at the hospital — the process was almost automatic. In stark contrast to her grandmother Gogo, Ms. Mahlase had no apprehension whatsoever about registering her newborn’s arrival into the world.

The changes experienced by the Mahlase family didn’t happen in a vacuum. They were a result of careful planning and strategic persuasion by the newly democratic South African government.

A scandal of invisibility

In 1994, the first democratically elected South African administration faced a significant challenge: only about one in four newborn babies were being registered at birth.

This was not surprising, given that the majority of South African citizens were still processing the social, spatial and economic injustices wrought by the Apartheid government, which for decades had used registration and identification processes to discriminate against citizens on the basis of race.

During those dark years, identity documents had been used to limit access to schools, parks, health facilities and even certain areas of the city. This embedded in black citizens a deep mistrust of government processes, particularly the country’s civil registration and vital statistic (CRVS) systems. In these systems, citizens were organized by race, with blacks at the bottom of a hierarchy built on bigotry. For some black parents, not registering the birth of their children was one way to shield them from this structure.

This impulse, while entirely understandable, had consequences for the children who were left unregistered, as well as for the functioning of South African society as a whole.

On a national level, data about the population’s characteristics — everything from age ranges to income levels — was chronically inaccurate, making effective provision of public services more difficult. And because blacks faced the most discriminatory policies, they were the least likely to register their children, and therefore the most severely undercounted when it came to allocating public resources. (This problem was exacerbated by the fact that census counters in black areas were often less rigorous than in others, since it was in the Apartheid government’s interest to undercount the black population.)

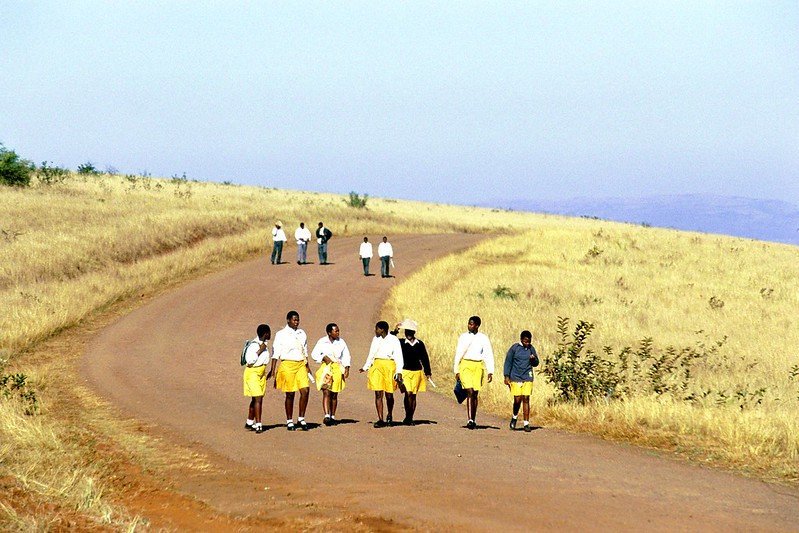

But more importantly, on an individual level, all those unregistered children missed out on a host of associated benefits and basic rights that are unlocked by birth registration. A birth certificate is a child’s first step toward acquiring citizenship and identity documents. In South Africa, no birth certificate can mean no access to social services such as schooling, grants and employment opportunities. It can also hinder access to health care, make getting a passport impossible and leave people vulnerable to exploitation and human trafficking.” This is why unregistered births are sometimes described as a “scandal of invisibility.”

With democracy, an opportunity

The end of Apartheid offered South Africa an opportunity to fix this. For decades, it had been a significant burden and risk to be registered as a non-white person. But after 1994, with the election of President Nelson Mandela, birth registration became not only an option, but a chance for millions to gain access to services and rights they had long been denied.

Still, getting parents to do it was a challenge. Once in power, the newly formed government had to work hard to change public perceptions of what birth registration meant. They realized it was critical to frame registration as a way to include rather than exclude — a step towards full citizenry, rather than toward systemic disadvantage, inequality and psychological trauma.

Part of changing these perceptions involved removing as many barriers to registration as possible. The government’s “basket of interventions” included four major efforts: increasing accessibility to registration, improving awareness of the importance of registering births, making registration easier and providing financial incentives when necessary.

Increasing access

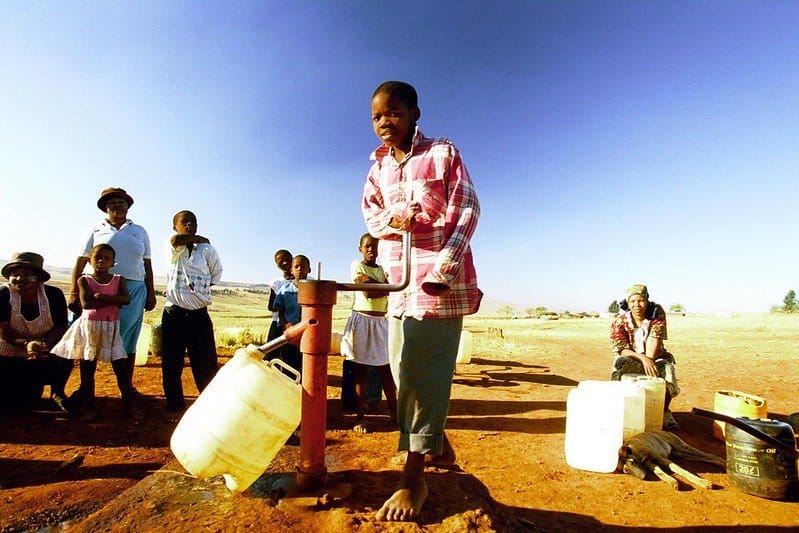

A big part of increasing birth registration was to get more women to give birth in health care facilities, or, at the very least, to bring their children to clinics when they got sick. To achieve this, in 1994 all user fees in health care facilities were eliminated for pregnant women and children under five. As a result, the number of babies born in institutional settings shot up, from 78 percent in the early 1990s to 95 percent in 2008.

Contributing to this was a major push to build more health care facilities, particularly in rural areas — over the course of the Mandela administration, some 1,300 new clinics were opened. For those who still couldn’t get to such facilities, the government dispatched mobile units to far-flung areas. These units offered other social services like financial assistance applications to entice people in.

Reducing Complexity

Prior to the reforms, many medical facilities couldn’t register babies on site. New parents had to travel to a separate government building, adding time and transportation costs. So, beginning in 1996, an initiative was launched to integrate registration points into health care facilities nationwide. Health professionals were trained in how to help new mothers fill out the forms. And antenatal and neonatal programs were used to demystify the process. Later, when internet access became more widespread in the early 2000s, online registration was made available in 400 health facilities across the country.

Raising Awareness

In part because so many black parents had only ever known birth registration to be a risk, many were unaware that, in most societies, it comes with many benefits. So a series of national campaigns and grassroots initiatives were launched to promote the perks of registration. These efforts were decentralized to conform to local contexts. For instance, the Villages and Townships Vital Registration Network distributed a bimonthly newsletter detailing the unique experiences of local areas.

Financial Incentives

In 1998, South Africa implemented the Child Support Grant, which expanded financial subsidies to black parents who had been denied them during Apartheid. To be eligible, parents had to produce their child’s birth certificate. This created a major incentive for parents to register their children’s births. And because the grant is offered specifically to low-income families — the ones who are often hardest to reach — those were the families whose birth registrations rose the most.

The effect was immediate. In the five years after the grant was introduced in 1998, the number of annual birth registrations increased by 400,000. Interestingly, right after the grant was introduced in 1998, late registrations surged in particular, a sign that parents who already had babies were returning to register them so they would be eligible for the grant.

A work in progress

South Africa’s first democratic elections were a watershed. Many citizens exercising their right to vote during this historic moment were, for the first time, engaging with the government in a meaningful way. This helped to change perceptions around bureaucracy and alleviate mistrust of civic processes. Instead of being a source of discrimination and pain, the same government services were now viewed differently — in the words of one researcher, “transform[ing] the idea of registration from one of surveillance to inclusive citizenship.”

The result? A country in which fewer than one in four babies was registered in 1991 achieved a functionally universal birth registration rate of 95 percent by 2012.

South Africa’s success with birth registrations shows how its citizens have been reactivated post-Apartheid. Still, there is room for improvement, particularly in the births of undocumented children. “There is a real need to improve birth registration practices at ground-level where the officials from the Department of Home Affairs often require a rigid application of the requirements in the Birth and Death Registration Act,” says Cecile Van Schalkwyk of the Legal Resources Centre. “They will often insist on documentation to which parents, guardians or caregivers do not have access. If they are unable to provide the required documents, the births are simply not registered.”

In situations where children have been abandoned, unmarried fathers are caring for children, a child is born at home without hospital documents or where undocumented migrants or refugees give birth within South African borders, the stringent requirements of the Birth and Death Registration Act prevent births from being registered. This affects thousands of children.

Consequently, Charlotte Manicom of the Scalabrini Centre advocates “for the birth registration of all those born within South Africa’s borders, regardless of nationality.” This is to ensure that all in South Africa can benefit from the country’s technological advances in birth registration.

While there is still much room for improvement, the country has already done the long walk with just over one million births registered in 2018. For families like the Mahlases, the changes have transformed the lives of a generation, and will continue to hold benefits for generations to come.