“This is about everyone,” says Hugh Somerleyton, still breathing heavily after tending to a band of horses on his farm in East Anglia, England’s far easterly region. “Rewilding should be a populist movement. It’s important that ordinary citizens feel like they are making real, tangible change.”

The 49-year-old conservationist, along with friends and fellow farmers Argus Hardy and Olly Birkbeck, are spearheading an ambitious effort to change the nature of rewilding. Built on the concept that natural areas will thrive if humans simply step back and let them heal, rewilding has caught on in places urban and rural, transforming everything from pocket-sized city parks to sprawling industrial farms.

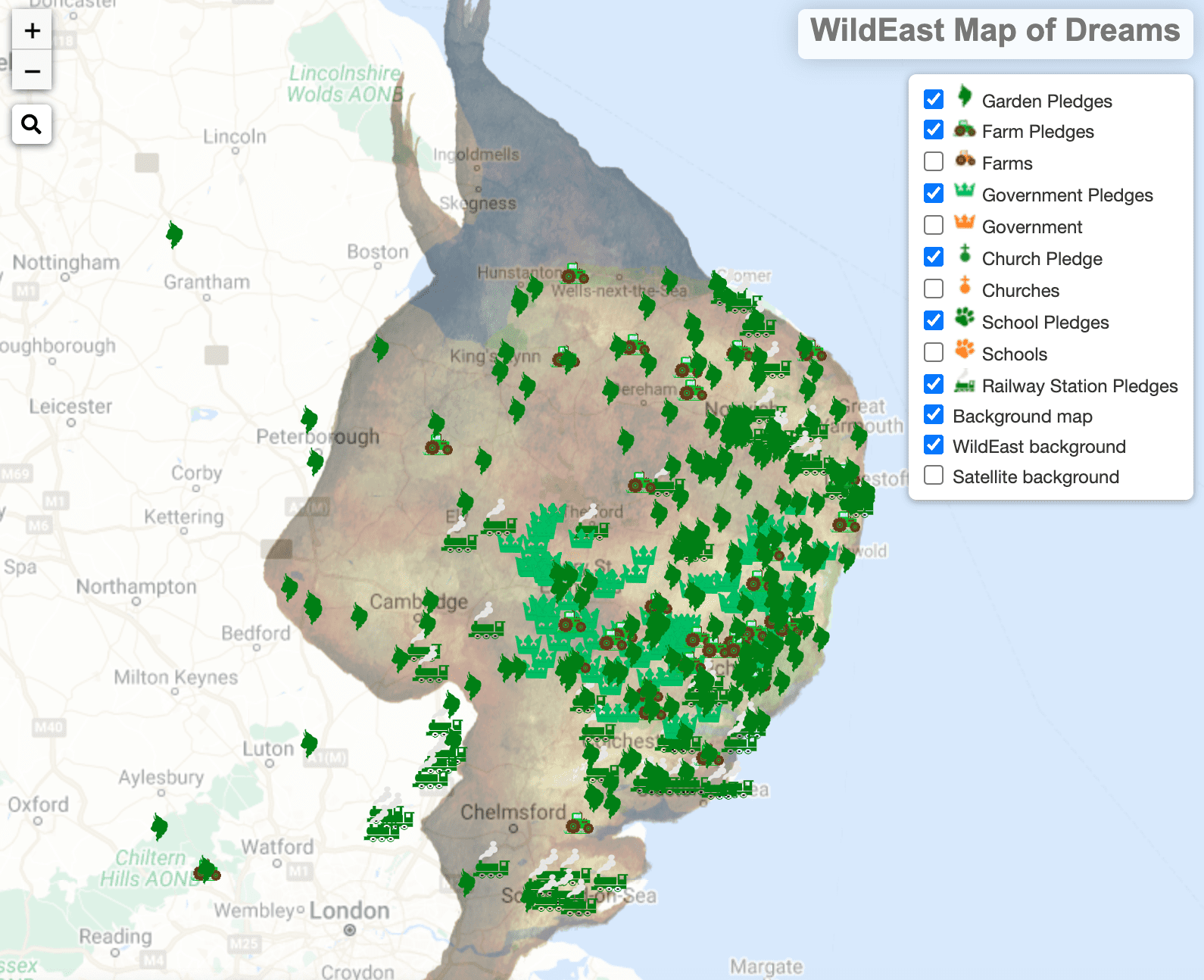

Somerleyton and his friends’ rewilding scheme is particularly ambitious. Known as WildEast, the radical project aims to give back some 250,000 hectares of East Anglia — one fifth of the entire region’s landmass — to wildlife over the next 50 years. The goal is to restore biodiversity in one of Europe’s most heavily-farmed regions by creating one of the world’s largest restored nature reserves.

Achieving this will require the buy-in of thousands of people of all walks of life across a far-reaching swathe of countryside — perhaps the project’s biggest challenge, and it’s greatest potential for transformative success. “We’re trying to democratize nature,” says Somerleyton, the son of a farmer, “and the preservation of it.”

From churches to train stations

WildEast was inspired by other rewilding experiments that came before it, such as the UK’s Knepp Estate, the Oostvaardersplassen reserve in the Netherlands and Spain’s Cantabrian mountains. Across the project area’s vast expanse, the trio plan to restore the region’s soil fertility through regenerative farming, and reintroduce species such as lynx, bison, pelicans and beavers. To the naked eye, the need for such restoration might not be obvious. But according to Somerleyton, while East Anglia, one of Europe’s most heavily farmed regions, is “visually beautiful, much of it is ecologically inert.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.East Anglia’s loss of biodiversity is emblematic of a nationwide problem. A landmark report published in 2019 by the British wildlife charity RSPB found that 41 percent of UK species have declined since the 1970s. It’s a similar picture across the globe, and last September, the UN revealed that none of the 20 global biodiversity targets agreed to by almost 200 nations in Japan in 2010 had been met.

“Britain is becoming incredibly nature-depleted,” says Richard Bunting, a spokesperson for the nonprofit organization Rewilding Britain. “We’re being outpaced by a biodiversity crisis. Large scale nature recovery and rewilding projects are hugely important to try and turn this around.”

But beside the impressive headline targets, experts say that what sets apart WildEast from other rewilding schemes is its focus on building a grassroots movement to achieve them, encouraging everyone from farmers to home gardeners and churches to private businesses across East Anglia to pledge one-fifth of their land to wildlife and help create a more ecologically-rich nation.

WildEast is also working with schools in collaboration with the charity Papillon Project to educate children about the natural world and the importance of biodiversity and sustainable farming, while also launching an accreditation system that provides labels recognizing the produce of farmers who sign up to the scheme.

According to Rewilding Britain’s Bunting, this people-led approach is helping to invigorate change like never before. “The empowerment and engagement aspect makes WildEast quite unusual,” he says. “It’s pioneering something quite special and allows people all across the community to get involved.”

A year on from WildEast’s launch, the project is showing green shoots of progress. A website known as the “Map of Dreams” that tracks rewilding efforts around the region indicates that the scheme has already met its target of recording 1,000 rewilding pledges by the end of 2021.

Somerleyton is leading by example in committing 1,000 acres of his 5,000-acre estate to rewilding, giving back grassland, heathland and wooded pasture to now be grazed by free-roaming Dartmoor ponies, rare-breed cows, large black pigs and water buffalo.

Many others across the region have begun to follow suit. One woman who inherited 100 acres of farmland is selling the farmhouse to pay for the land to be returned to the wild. A transport operator has pledged 56 railway station gardens to nature. And a vicar at the All Saints Chedgrave Church in Suffolk, who has pledged 20 percent of the church’s gardens to rewilding, has also installed bird boxes and insect houses, planted wildlife plugs and ceased mowing certain parts of the land.

“It sits with our aspirations environmentally,” says Reverend Alison Ball. “We have to take care of the earth responsibly. But WildEast also legitimizes what we’re doing in our churchyard — we’re not just one little church on its own. I think it’s absolutely fabulous, and the way that they are creatively trying to engage people with it.”

Ball says the impact is already visible: a recent flowering plant survey has revealed several more species than there were last year, with the gardens now teaming with flowers, long grasses and butterflies.

But it has not all been steady growth for WildEast. For one, Somerleyton admits that building a sustainable funding model has until now proven tricky. “It’s early days and we’re not well financed,” he says.

The three founders have so far each invested around £50,000 (USD$70,000) of their own money, in addition to around £15,000 of donations from the public. For the project to be successful, he says other income streams such as national and regional funding grants, corporate investment and crowdfunding must be established.

Another key challenge is gaining the support of farmers, some of whom see the rewilding movement as a threat to their livelihoods — if land is rewilded, they believe it cannot be farmed. “But the reality is that we have enough unused land in Britain to produce enough food and still achieve our rewilding goals,” says Somerleyton.

Nonetheless, signs are that their message is gradually filtering through. He points out that around 70 of the 1,000 pledges received by WildEast have been made by farmers.

“It will take us time and effort to convince them,” he says. “But a year ago we didn’t expect all of these individuals, institutions and companies to be on board. We didn’t expect all of this momentum. We feel like the wizard from The Wizard of Oz. Anything is possible if we work together.”