Charles Hervé-Gruyer’s most important tool looks like a wide fork crossed with a huge pasta machine on wheels. With his foot he presses the long row of tines into the ground. Pulling the tool towards him, the tines emerge. The rich scent of fertile earth fills the air. “Worms, woodlice, beetles, microorganisms,” says Hervé-Gruyer. “The whole diversity of nature remains undisturbed.”

With rudimentary tools and minimal labor, the Bec Hellouin farm in French Normandy is a vision of what farming could become — not an advanced, high-tech endeavor, but instead, one that draws on techniques used in the past to feed fast-growing cities before large-scale industrial farming existed.

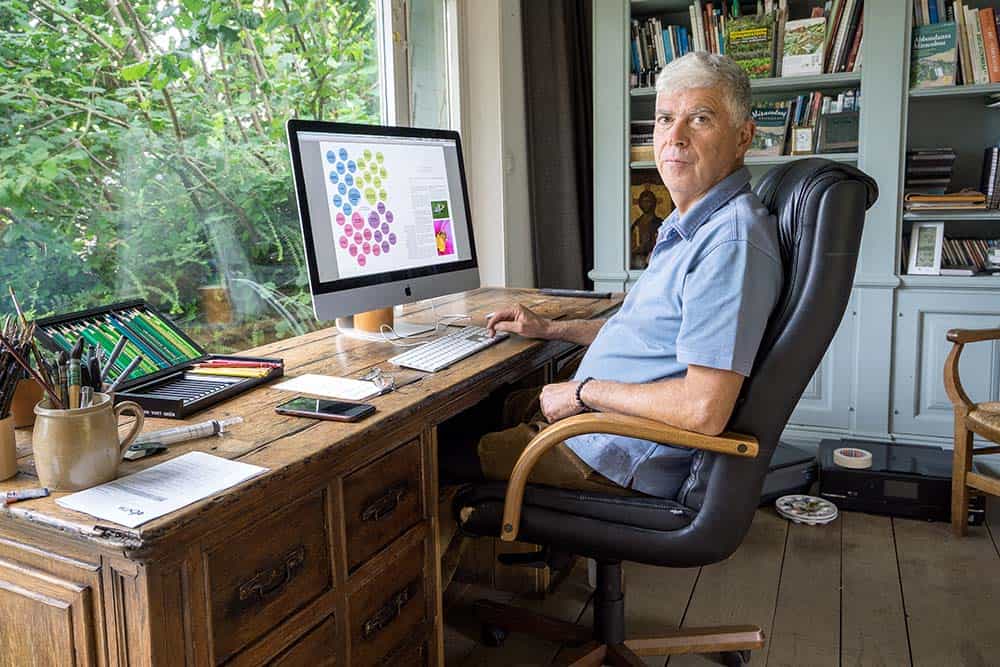

Just four people — Charles, his wife Perrine and two employed gardeners — work the beds at Bec Hellouin. They work exclusively by hand, yet the farm produces yields that have stunned agricultural researchers. “Critics often say we want to go back to the Stone Age,” says Charles, “but this is about the future.” Indeed, Bec Hellouin seeks to answer one of the most pressing questions facing mankind: How can we feed the world without clearing more forests in an era of climate change?

The first thing you notice upon arriving at Bec Hellouin is the sheer density of crops. Pumpkin plants meander over beds where zucchini are in bloom. Turnips, cabbage, leek, chard and artichokes sprout from the earth. Beans tendril up maize plants into the blue sky, over which a fresh wind drives black and white clouds. And where nothing grows at the moment, mulch and rotting plants nourish the beds. Bec Hellouin’s cultivation area is hardly bigger than a soccer field. Nevertheless, Charles and Perrine provide organic vegetables for about one hundred people year round.

There is no tractor or plow in this place of constant growth. The farmers do not use fossil fuels, nor artificial fertilizers and pesticides. The manual work saves costs and reduces their carbon footprint. But there is also another reason. A tractor designed for modern farming could not plant more than three rows of carrots on the barely one-meter-wide strips utilized by this farm. At Bec Hellouin, four times that density of crops is grown in that amount of soil. “We cultivate radishes, carrots, lettuce and cabbage in 12 rows on this space,” says Charles.

How can so many vegetables thrive on such a small amount of land? The trick is in finding ways for the crops to complement each other. Radishes grow quickly and provide shade for the carrots, which need a cool and humid microclimate. When they have harvested the radishes and lettuce after six to seven weeks, the gardeners fill the same space with cabbage. And because the bed is densely overgrown, moisture and humus are retained, preventing unwanted plants from finding purchase in the soil.

The farm’s sensational yields have attracted the attention of scientists from France’s National Institute of Agricultural Research, who meticulously counted and weighed the harvests on Bec Hellouin for four years. “At first they did not want to believe the result,” says Charles with a smile. Based on the prices for vegetables from organic farming in Normandy, the Bec Hellouin yield was worth 55 euros per year per square meter, many times more than what conventional farms earn.

Even the extremely dry summers of the last three years have been well managed by the farm. The soil, the diverse root network and the dense vegetation make the ground like a giant sponge that stores moisture. In addition, the soil extracts carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Basically the farm works according to the principles of permaculture. The land is used permanently, and the plants thrive in a cycle of full interactions oriented towards nature. They use sunlight at different altitudes, give or consume nutrients and prepare the soil for each other with their roots.

“But permaculture is just one framework that we are expanding in many ways,” Perrine explains in the farm’s greenhouse. Behind her, tomatoes, basil, peppers, figs, cucumbers, lavender, Chinese cabbage, spinach and eggplants grow. Again and again, she disappears into the green thicket, cuts off ripe fruits, pulls out withered leaves and reappears. Even bananas and citrus fruits thrive in the usually unheated greenhouse. This is made possible by raised beds, in which compost, leaves, branches and dung ferment, creating heat. The inhabitants of a small henhouse in the greenhouse contribute even more heat, as well as scrape and fertilize the soil.

Perrine and Charles learned many of these farming tricks from books written by Parisian market gardeners in the 19th century. “They were able to feed the urban population by growing in a very confined space,” says Perrine. Other influences are the forest farmers of Amazonia, Asian research on efficient microorganisms and the bio-intensive agriculture practiced by the American farmer Eliot Coleman.

Other farms around the world follow these methods, too. There are associations for education and networking, such as the Australian-American Permaculture Institute. The U.S. Department of Agriculture provides guidance and further literature. But perhaps nowhere have these ideas been implemented and examined in such intensive practical application in cooperation with renowned scientists as at Bec Hellouin farm.

When Perrine and Charles bought the land 14 years ago, it could only be used as pasture because of its thin layer of humus. Predominantly using biomass from their own farm, they created the most nutrient-rich soils in the region — a fact proven by a study conducted by universities in France and Belgium. Due to the attention they’ve received from the scientific community, for the time being the couple has stopped producing for consumers to devote themselves to deeper research of their methods full-time.

This research is unfolding in real time. On the 12-acre farm, a forest garden of fruit and nut trees is growing, with small clearings for vegetables and old varieties of grain. The forest stabilizes the microclimate and protects the farm from extreme weather events. And it provides fruit, herbs and nuts. “We want to record yields for several years,” says Charles. First detailed figures will be included in Bec Hellouin’s next annual report. He reveals that they have been able to earn an average of 44 euros per working hour in the forest garden.

The couple cultivates these grains with the help of draft animals. Here, too, they want to prove that worthwhile yields can be attained without motorized machinery. This is not just for novelty’s sake — the majority of people in low-income countries rely on small farms, which they work mainly by hand. Charles is certain: “These farmers feed the world,” he says, “and so they must in the future.”