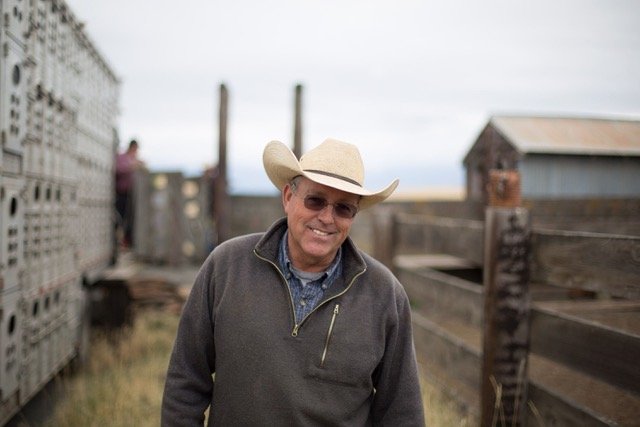

A few years ago, Dan Probert was managing a ranch in southeast Oregon when he learned that the 12,000-acre Lightning Creek Ranch on the nearby Zumwalt Prairie was for sale. After over two decades of managing other people’s ranches, he realized that this was a chance to fulfill a his long-time dream of setting up on his own.

The problem was the cost: a cool $2.6 million.

So Probert started digging around for a financing solution. In his effort, he learned that The Nature Conservancy (TNC), a conservation nonprofit, already owned and managed a parcel in the prairie, and was looking to buy more.

Probert reached out, discussions came together and, within a few months, they struck a deal in which TNC, with the help of funding provided by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, the Climate Trust and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, made a payment to Probert allowing him to buy the ranch. In exchange, he agreed not to till or develop the property in perpetuity, while retaining the right to use the land to raise livestock.

“The financial aspect was appealing, but what we liked the most was that [Lightning Creek] was going to remain a working ranch while also protecting the land for the following generation,” says Probert, 58, who runs the operation along with his wife Suzy.

The contract, called a conservation easement, is a legal agreement that allows landowners to donate or sell the right to develop their land to a nonprofit or government agency, which manages the land for conservation. Under these programs, landowners retain ownership of the land and can continue to use it for activities such as farming, forestry and hunting. Such easements have become increasingly popular as a way to conserve and restore the country’s prairies — or what’s left of them.

Grasslands used to cover large swathes of what later became the US before Europeans homesteading on the continent began plowing them for agricultural fields. Today, only about half of those original prairies survive, and the loss continues at a blistering pace. A 2020 study found that the US lost an average of 1.1 million acres of grasslands — an area larger than the state of Rhode Island — every year from 2008 to 2016.

Yet prairies are vitally important ecosystems that deliver a multitude of services. These grassy biomes provide habitat for numerous wildlife and insect species, many of which are essential for pollination, and are home to hundreds of plants that cleanse water and hold soil firm, preventing erosion. They also sequester a significant amount of carbon. Researchers have found that grassland plow-up in the US puts as much CO2 into the air annually as 31 million cars.

“Prairie grasslands really are a critical ecosystem, but they are one of the most endangered and least protected habitats in the world,” says Tyler Lark, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin who has studied grasslands for the past decade.

Lately, however, there seems to be a growing awareness of the importance and benefits of grasslands. Last year, the US government launched a $1 billion program to help fund projects focused on conservation of land and waters. The Senate also introduced the North American Grasslands Conservation Act, legislation that, proponents argue, would foster grasslands protection by promoting voluntary partnerships between states and private landowners.

The effort underway at Zumwalt Prairie is a prime example.

Stretching 500 square miles between the Wallowa Mountains and Hells Canyon, the Zumwalt is the largest bunchgrass prairie in North America. And like most of the surviving grasslands in the US, this vestige of pre-settlement vegetation is largely in private ownership.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.In the 2000s, TNC bought a total of 33,000 acres in the area and established the Zumwalt Prairie Preserve, the largest private nature sanctuary in the state, with the goal of protecting its rich biodiversity. But TNC’s lands comprise just one-tenth of the prairie, which has been prized grazing land for generations of local ranchers.

With the Probert family’s purchase, Lightning Creek Ranch is the first part of the prairie outside the TNC preserve to be protected. “We all value keeping it in grass,” says Probert. ”That’s the common thread.”

As a conservation-focused cattle operation, the owners of Lightning Creek have committed to holistic management. In particular, they implemented rotational grazing, a grazing strategy that involves frequently rotating livestock to different portions of a pasture. Once a section is grazed, it is then rested for a period to let it grow back for the next grazing.

The practice is an attempt to mimic the way herds of wild herbivores such as bison used to graze the land before fences, explains Jeff Fields, Zumwalt project manager for TNC in Oregon. “To thrive, grasslands need occasional disturbance, such as that provided by fire or grazing,” he says.

As they trample the ground when they feed and look for water, cattle aerate the soil and spread organic matter, improving fertility and stimulating growth. But just like fire, Fields points out, timing and intensity are crucial in order to avoid overgrazing, “which can strip the land of nutrients needed to support grass growth.”

Probert says the agreement with TNC doesn’t dictate how many cattle he can keep in a pasture, or how long he can leave them there. “We have maximum flexibility,” he says. In fact, the grazing plan is built on specific goals. “It’s based on the outcomes we want to see on the landscape — this is what drives us.”

Since 2017, the Probert family has worked with TNC on other habitat improvement projects, including invasive weed removal and riparian plantings along the creek. They also helped the nonprofit organize a number of elk hunts to control the population and keep the animals moving around to prevent browsing on trees that provide habitats for raptors.

TNC routinely assesses Probert’s pastures using a mix of satellite technology and traditional techniques. Over the past five years, says Fields, Lightning Creek’s pastures have constantly scored good results. “In short order, the soil on the ranch is healthier and holds more moisture, grass is more productive, and biodiversity has increased.”

The partnership is paying off financially, as well. Probert says granting development rights to TNC has helped him reduce the land cost to one that is more manageable for his family. The sustainable grazing methods also allow him to use the land more efficiently. “When we started out five years ago my ranch ran 1,000 head. Now we’re running 1,200 head on the same land area,” Probert says. Finally, keeping the ranch’s carbon-rich soil undisturbed is helping the Proberts find a new source of income in the form of carbon credit sales.

Looking back, Fields recalls when the local ranching community was wary of TNC’s involvement with the Zumwalt. “Cattlemen and conservationists haven’t always been natural allies when it comes to managing grasslands — and for a reason,” he says with a smile.

But over time TNC managed to demonstrate that the goals of livestock producers and conservationists can coexist. The partnership with Probert, Field argues, is “a living document that both ranchers and the prairie can prosper if there’s a common purpose.”

Currently, conservation easements protect more than 30 million acres of private land across the US — about the size of Louisiana – a significant increase from the approximately 500,000 acres recorded in 1990.

“Conservation easements have been shown to be an effective way to protect large areas of private land as they can be implemented at different scales, from small, locally-held conservation easements to larger, regionally or nationwide programs,” says Fields.

TNC’s ecologist acknowledges there are barriers to greater uptake of easements, with hurdles ranging from limited financial and staffing resources by holding entities or land trusts to purchase easements to a lack of awareness from landowners about the benefits they can provide, as well as concerns regarding perpetual nature of most conservation easement agreements.

Despite these challenges, he says, “they offer important opportunities that must not be squandered if grasslands are actually to be saved.”