When Anna Heringer invited her architecture students to an excursion into the Austrian Alps, she waited until they had reached a high plateau in the mountains before she revealed a surprise: She hadn’t booked a hotel for the group. Building a shelter for the cold October night was the purpose of the trip.

“Immediately, the egos shriveled,” Heringer remembers. “Groups formed to distribute the tasks, and the students forgot their classroom competition.” The excursion happened during the European refugee crisis of 2015, and Heringer had assumed at least half of her students at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich would want to design emergency housing. To her surprise, “they all wanted to design prestige projects, business centers and the like.” She shakes her head. Thus the trip to the mountains. “I wanted to bring them back to the essentials,” she says with a smile. “When you design for prestige, you choose a place where the building can be viewed from the best angle. But when you’re exposed to wind and weather, you choose a place that protects you. From time to time, you have to come back to what matters.“

This anecdote perfectly illustrates Heringer’s building philosophy. She had experience building forts in the forest because she had grown up as a Girl Scout in the Bavarian countryside. To her, sustainable, ethical construction means relying on what nature willingly offers as construction material. And it means focusing on the essential benefits for a building’s inhabitants instead of on the builder’s ego.

Heringer is simultaneously an internationally revered pioneer of sustainable construction and an outsider; a trailblazer who combines traditional clay buildings with innovative technology and yet she never tires of emphasizing that she is following in the footsteps of the most ancient builders. After all, clay cities have lasted for centuries in ancient Europe, Asia and Africa. One-third of the world population lives in clay buildings but most architects in the West disregard it as dirt.

Her first building constructed by hand from clay, bamboo and local fabric, the METI school in Bangladesh, won the renowned Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2007. She has won the Global Award for Sustainable Architecture, the Obel Award, for the sustainable Anandaloy therapy center in Bangladesh in 2020, and the New European Bauhaus prize for an Ayurvedic therapy center, to name a few. Since 2010, she has held the UNESCO chair for Earthen Architecture, Building Cultures and Sustainable Development. She has taught at Harvard, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich and other prestigious institutes.

The 45-year-old architect just returned from Ghana where she is constructing an education campus from local red clay for the Catholic Church, which will also serve as a training center for local craftspeople. Since Pope Francis encouraged his followers to adhere to sustainable development, the campus is a showcase project for sustainable and social progress. “If I had built the construction with cement, few women would have been employed on the site, but with clay as the main building material, the project becomes a catalyst for local development,” Heringer says via Zoom from her office in her hometown of Laufen near the German-Austrian border.

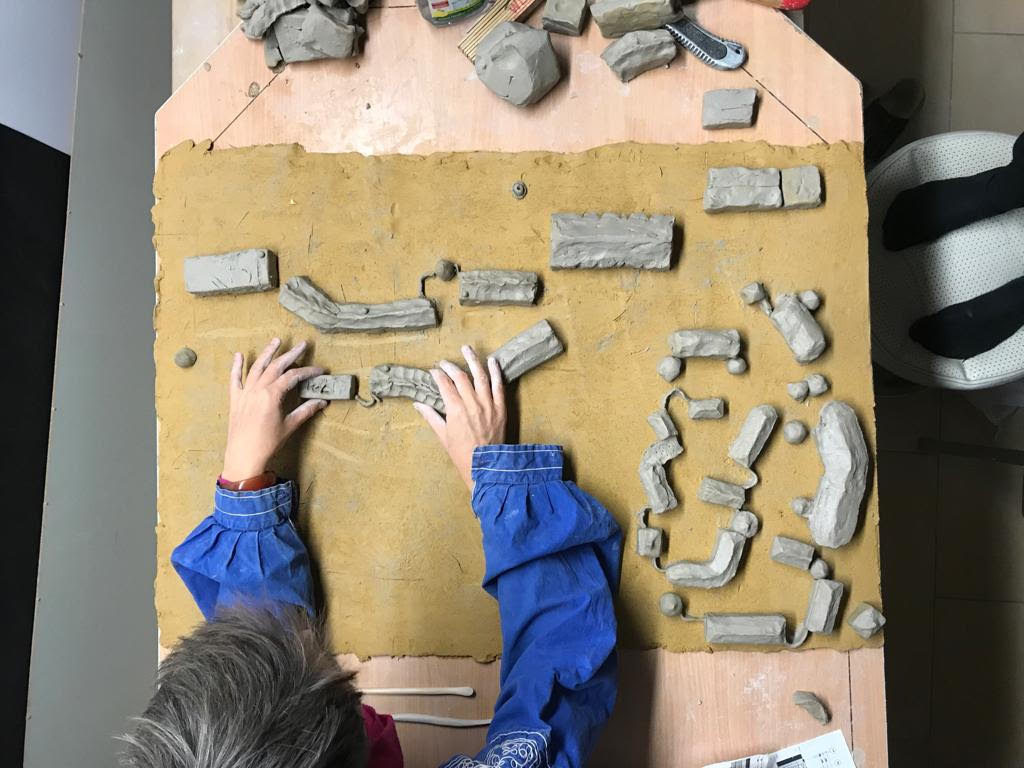

Without makeup, her blue eyes beneath a brunette pixie cut flash with humor and intensity. She holds her hands up to the video camera, noting with satisfaction that the clay from the morning’s creative sessions is still stuck under her fingernails. Heringer doesn’t draw her designs on paper or a screen. She manifests her ideas in clay. First, she researches all the parameters of a project. But then, in a process she calls claystorming, she tries “to become very still, to empty myself. We all know that the best decisions come from the gut.” She starts modeling her ideas with clay “until the fingers take over, very intuitively, until it feels right. With clay, you immediately see if it works. You’re all in the details and yet you still see the whole picture.”

This method results in buildings one can only describe as sensual; vibrant, earthy and colorful, they speak to all senses. In a two-story primary school in Bangladesh, she built caves together with the students for them to use as rooms to study and read. In the cathedral of Worms, Germany, she invited the church community to foot stomp the earthen altar. And during her guest tenure at Harvard, she and her students constructed clay structures in front of the university’s gray facade. “It was fantastic to see many passersby spontaneously caress the material,” she says. “Normally, we don’t feel like touching buildings, but clay is so sensual, it simply attracts people.” She laughs because building with clay had never been taught at Harvard before. “I’m the woman who brought the dirt to Harvard.”

She sees what we have under our feet as the best building material. We forget, she says, that mankind has had the most natural building materials in abundance since the beginning of time. “Building with earth is the most beautiful and also the healthiest,” she says. “I want to show people that this material isn’t just the dirt under our feet but really precious construction material with which we can build very creatively and specifically.” Most architects do the opposite, she laments. “We excavate foundation pits and then pay to dump the earth in landfills. Sustainability for most people means to install solar panels on the roof, but hardly anybody questions what’s below the roof.”

Cement is one of the biggest climate killers on earth. Emitting 2.8 million tons of CO2 worldwide per year, the cement industry is responsible for nearly eight percent of worldwide emissions. By contrast, a crack in clay is easily repaired and if a building is no longer needed, the clay can simply be returned to earth, without toxic waste. Heringer, too, might occasionally choose cement or stone as the foundation for a building. But, she says, “I would like to see the true cost of cement built into its price, including its environmental cost. How well can a material be recycled? How much energy do I need to spend to reuse it?” That cement should therefore cost at least double what it costs now is an argument she has repeatedly stated at international architecture and building conferences. “I might as well have thrown a bomb into the meeting,” she says, describing the stoney reactions at a conference organized by Holcim, one of the biggest cement distributors in the world. “As a woman, it’s already not easy in the construction world. And yet, we architects have to speak up for the truth.”

‘Include the planet in our plans’

Shortly before Heringer graduated from the University Linz in Austria, she had an existential crisis.

“Will I build carports and calculate the width of socket boards for the rest of my life?” she mimics the despair she felt as a burgeoning builder. Then she attended a workshop with Martin Rauch, a well-known Austrian ceramic artist and clay construction expert. “As soon as I had my hands in the clay, I knew, this is it. This is my element.”

What Heringer wants to achieve through architecture is nothing less than “making the world a better place.” This is the reason she chose this profession, these sustainable materials and why she uses her trade as a lever for social justice. The school in Bangladesh, for instance, cost $35,000 to build, and the bulk of the money went to local craftsmen and women who stomped the clay with their water buffalo, harvested the bamboo for the roof and weaved the fabrics. “I want the funds to invest in the crafts, to benefit the people, and not some company or global conglomerate.” And of course, she adds, “not harm the planet but stay in harmony with nature.” She raves about the beauty of the soil that varies in color and texture from soft and sand-colored in Bangladesh to gray in Boston and bright red in Ghana. “It is such a beautiful material, a fascinating universe with many nuances where one is not limited. Form follows love.”

It is no coincidence, though, that you find most of her buildings in Asia and Africa, and only a handful in Europe. In her hometown of Laufen, she built an earthen wall into her home. In the small Bavarian town of Rosenheim, she is currently constructing an Ayurvedic retreat center from clay and untreated local wicker. And in Traunstein, she just got the go-ahead to build a sustainable school building on a Catholic campus though she lost the battle to build the entire campus out of clay.

“In the global South, the most sustainable solution is usually also the cheapest,” Heringer states. “But in Europe, it’s the most expensive. You really only need the dirt and the labor, but manpower is hardly affordable here. Such materials that are healthy for the planet and for society because they create jobs are punished here in Europe whereas others are subsidized. I’m really angry about this.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.For every earthen construction in Europe or the US, she needs to apply for a special building permit. “In the global South, we are guided by intuition and common sense,” she says, whereas in Europe and the US, “you always end up violating some rule or norms. Construction here has become so counterintuitive, so far removed from common sense and trust.” Construction decisions in the Western world are ruled by fear, she has found, “and fear is always a bad adviser.” Construction companies and insurers want to safeguard through “normed construction materials and parts,” Heringer complains. “This makes innovation very difficult.” She’d love to question every construction rule and every norm. “Cui bono? Who profits?” she asks and answers, “Not the planet. We have to include the planet in our plans, because the construction business completely disregards that we are harming the health of the entire planet.”

Sure, she says, to build with cement is simpler. Soil requires the flexibility to take into account the local climate, the properties of the earth, the local culture — but this is exactly what interests her.

That she is as much artist as architect is visible, literally. When she started visiting Bangladesh, she noticed that nearly all women were trained as tailors, “almost all of them to produce fast fashion in factories under inhumane conditions,” Heringer says. She decided to turn things around. Together with a collective of local women she started a fashion label called Dipdii Textiles that gives used fabric new life as artful unique second-hand pieces. She is wearing a purple shirt with black sleeves from her own collection, sporting her motto in bold gold letters across her torso: “Sustainability = beauty.”