This story is part of The New Climate Economy, a series about how the Inflation Reduction Act is accelerating investments in climate action. It is produced in partnership with Nexus Media News.

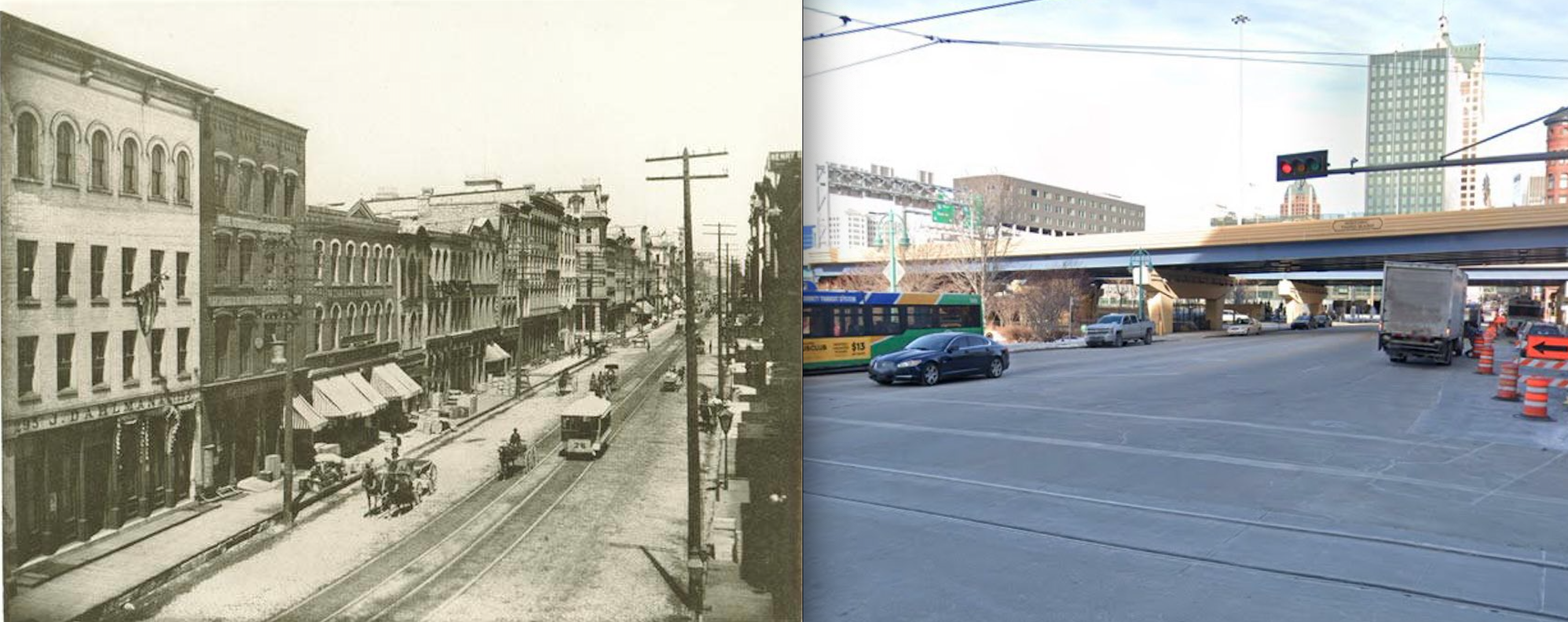

In 1995, Peter Park, then a professor at the School of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, began working with his students to make a case for tearing down a freeway. Their idea was tantalizing: replace a section of I-794, an elevated highway that ran through downtown Milwaukee, with a pedestrian-friendly boulevard. In doing so, the reclaimed space that would connect the city’s trendy Third Ward, laced with boutiques, patio dining and art studios, with its downtown, adding dozens of developable acres of land right smack in the city center.

“Save your money,” Park recalls telling a Milwaukee Journal business reporter at the time as they discussed impending repairs on the controversial section of the highway. “Imagine it’s not there right now.”

Three decades later, I-794 still stands, but calls for its removal have grown in volume. Leaders of Rethink 794, an initiative organized by the environmental advocacy group 1000 Friends of Wisconsin, believe that beneath that freeway sits 32.5 acres of endless possibilities — a $1.5 billion goldmine that could increase the city’s tax base, provide housing, enhance connections between parks and trails, and reduce emissions.

It’s easy to see why organizers of the effort have such high aspirations for the area, when you consider that just a mile or so north, the teardown of another freeway, the Park East, is a shining example of what can happen when public officials decide that sometimes less is more, and slower is better.

The teardown of Milwaukee’s Park East freeway, which began in 2002, allowed Park, who was by then the city’s Planning Director, to remap the area, reconnecting it with the new and existing street grid system. Nationally, the Park East removal became a cause célèbre among urbanists — a daring landmark project that helped propel an era of urban highway removal nationwide.

The Park East project created an opportunity for cities to think more strategically about how highways serve a given area and whether it still aligns with current needs, explained Ruth Steiner, director of the Center for Built Environment at the University of Florida.

“Rebuilding or repairing what’s there may not be the optimal solution,” she said, adding that many historic freeway projects have become obsolete or are in need of major overhauls.

The removal of the Park East freeway was made possible by an influx of federal money. Now, a similar wave of infrastructure funding is about to flow into cities once again, as billions of dollars from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) transform major projects from pie-in-the-sky aspirations to shovel-ready realities. In Milwaukee, the removal of I-794 — the very idea that Park and his gang of novice architects introduced three decades ago — suddenly feels within reach.

It’s hard to overstate the transformative effect of the Park East teardown, completed 20 years ago. It opened up 24 acres of prime real estate beneath and around the former highway, much of which was being used for parking. Since the teardown, the area has seen increased property values, created more space for pedestrians and recreation, and generated over $1 billion in private investment. Moreover, its rebirth as a lower-capacity boulevard has decreased emissions from the thousands of vehicles that once passed overhead daily.

Surrounding neighborhoods have also seen investment. To its north, a derelict area that for more than 100 years had churned out cans of Pabst Blue Ribbon has been revitalized as the Brewery District. A swathe of new mixed-use developments, parks and co-working spaces have sprouted there and in other surrounding neighborhoods, among them the Park East Lofts. Two blocks east is the striking headquarters of the Fortune 500 staffing company ManpowerGroup Inc., a 292,000 square foot building situated along a bend of the Milwaukee River.

Undoubtedly, the most recognized of the Park East redevelopment projects was the construction of the Fiserv Forum, home court of the Milwaukee Bucks, and the adjoining Deer District, a mix of indoor and outdoor entertainment and community spaces.

Public funding of the Bucks arena did net its criticism, most prominently from the group Common Ground, a nonpartisan group of community organizers. They argued that the funds used to build Fiserv should instead be invested in Milwaukee County athletic facilities and playgrounds and to fix blighted homes. Opposition cooled eventually, as minority-owned businesses and workers of color were hired to construct the project, and public events held at the Deer District became a unifier in a city known for its entrenched segregation. Overall, the highway removal project and subsequent development has been viewed by the community and public officials as a major success that could be replicated elsewhere in the city — for instance, around I-794.

“One-hundred percent we looked at Park East and what happened there as an example of what could happen again,” says Gregg May, transportation policy director at 1000 Friends and leader of the Rethink 794 initiative. “They said it would ruin traffic flow, but none of that really happened and people now see the benefits of having it removed.”

The Park East teardown is part of a wave of freeway removals that have spanned from San Francisco to Boston in an attempt to reverse engineer an era of car-centric urban planning. According to Park, the U.S. Interstate Highway System, begun in 1956, was never meant to cut through dense urban neighborhoods. Nevertheless, public officials became enamored with the idea of building highways to quickly move people between cities and suburbs. In the process, neighborhoods across America, often communities of color with the least voice and political power, were destroyed, while others were burdened by physical and social ills exacerbated by highway construction, Park says.

“To me it’s such an un-American idea to use taxpayer money to devalue real estate, which is what these highway systems did,” Park says, describing it as an ongoing equity issue.

Milwaukee was no different. In the 1960s the Brew City laid plans to encircle downtown with a series of freeways. Construction on the Park East, a major component of that plan, began in the early ‘70s. It erased landmarks and homes, and cut off sections of the city from downtown, according to John Gurda, a well-known Milwaukee historian.

“It screwed up those neighborhoods,” Gurda says. The city continued to buy properties and clear land to move construction along the lakefront to the south suburbs, before pushback compelled Mayor Henry Maier to veto federal highway funds for the project, stopping it in its tracks. The incomplete result, Gurda says, “became a pretty quiet backdoor entrance and offramp to downtown.” For several years it also lent the Hoan Bridge, which was never connected to the Park East on the north end, the nickname “Bridge to Nowhere.” The iconic bridge was even featured in the classic 1980 film The Blues Brothers, during a chase scene that ends when police almost crash off of the edge of the half-finished bridge.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Many other neighborhoods in Milwaukee, including historic Bronzeville, known as the heart of the city’s Black community, met worse fates. Known for its bars, shops and restaurants, Bronzeville was razed to build parts of the I-94 and I-43 freeways.

Clayborn Benson, founder and executive director of the Wisconsin Black Historical Society/Museum, said that while many of the houses and buildings in Bronzeville were aged and dilapidated, their destruction led to mass displacement and the loss of many homes and businesses, owned by both Blacks and whites.

“Those homes could have been repaired by the city or state, but instead it became more important to move people smoothly from their homes to downtown,” he said. “That was the ultimate goal.”

Its ripple effect is still felt today, he said. While many displaced Black residents moved to newer housing stock in cleaner neighborhoods, they were forced to buy homes at higher prices. Some couldn’t afford to. Meanwhile, white residents in the area continued to move out to the suburbs the new freeways were designed to serve, leading Milwaukee to become the hyper-segregated metropolis it is today.

“Eventually, those neighborhoods became economically deprived,” he said. “You can still see that today, just like you can see economic development in certain areas of the city and not others.”

In addition to the many neighborhoods that were destroyed so that highways could run through them, there were also large residential sections of the city razed for highway projects that never came to fruition, evident by the many vacant lots on the city’s primarily Black North Side.

For the residents whose homes were spared but now bordered highways, their reward was an increased exposure to pollutants, higher asthma rates and other safety concerns.

Eventually, the Hoan Bridge was connected to I-794, while the Park East remained a stain on the city until John Norquist, who replaced Maier as mayor in 1988, pushed to have it removed. That process involved adopting a downtown plan that called for the removal of the Park East Freeway and replacing it with a mixed-use district,, says Park. A convergence of official support and federal funding helped the teardown process start in 2002.

Twenty years later, Steve Morales, a partner at Rinka Architects who helped to develop the Deer District, says the Park East teardown opened up possibilities that are still coming to fruition.

“There’s really still more to do, but we have already made some really great possibilities come true,” he says.

His firm’s plan for the Deer District, which was supported heavily by the City of Milwaukee and the Milwaukee Bucks, was for the space to bring together residents from all over the city and turn the plaza, in particular, into the city’s living room. Much of this vision has been realized: today, the space serves host to fitness classes, a marketplace, and small fairs and festivals.

“We all envisioned the Deer District as a way to give people from all walks of life and from different communities a place to call their own,” Morales says.

While the teardown of the Park East freeway was supported by local and state funds, its main investment came through an influx of federal money. Over the last several decades, a series of legislative acts and initiatives — the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA), the Bipartisan Instructure Law, the Reconnecting Communities Pilot and the Infrastructure for Rebuilding America Program — have provided local entities more power to design, and in some cases remove, highways and other roadways.

But all of these funding sources are dwarfed by the federal government’s latest initiative to address inequities and meet President Biden’s climate goals, the Inflation Reduction Act. The IRA earmarks a whopping $3 billion for improving roads and “removing, replacing, or retrofitting highways and freeways to improve connectivity in communities” through Neighborhood Access and Equity Grants. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law also set aside $1 billion for the US Department of Transportation’s Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program.

Park sees the IRA, and other available federal funds, as an opportunity for cities, including Milwaukee, to move further away from a polluting and costly highway system that burdens local, state and federal systems, towards a healthier and more economically sustainable approach.

“It’s the difference between spending public money on things that cost more to maintain in the future and realizing that those things are not necessary anymore,” said Park, who advocates for the removal of highways across America. “We need to think about the long-term benefits rather than the short-term inconvenience of traffic congestion.”

Ruth Steiner, a Wisconsin native who said the Park East freeway helped spur her interest in urban planning, said that the infrastructure funding has given cities more opportunities to align transportation with the needs of residents and neighborhoods.

“Are [the freeways] dividing people or can it be redesigned to slow down traffic to allow people to have access to places where they want to go?” she said. “Transportation facilities are necessary, but how do you fit the great roadways into the other activities they are engaging in the city.”

1000 Friends of Wisconsin and Rethink I-794 teamed recently with local architects Taylor Korslin and Xu Zhang to produce renderings of what both Clybourn Avenue — the section of boulevard that would be extended into the area blocked by I-794 — and the lakefront could look like without the freeway.

“There’d be more room for walking and biking and it would strengthen the tax base in Milwaukee,” Gregg May says.

The group’s next goal is to convince city officials to conduct a boulevard study that measures the impact that a teardown could have.

If history is any lesson, a removal of that section of freeway, if it happens, could take years. Currently, the plan is to rebuild I-794 at a cost of $300 million, May says. Meanwhile, plans for another highway project west of that interstate have been announced. A 3.5-mile section of East-West freeway in Milwaukee will be widened from six to eight lanes, easing traffic flow and improving safety, according to transportation officials. That plan has met pushback, however, including from 1000 Friends, who have advocated for the expansion to be scrapped in favor of more pedestrian, transit and biking features and reduced emissions.

As those battles play out, another freeway deconstruction project in Milwaukee is also in the works. Donna Martin-Brown, director of the Milwaukee County Department of Transportation, says local and state officials have applied for funds to remove the I-75 interchange, also a remnant of the city’s plan to encircle Milwaukee with highways. The funds they’re seeking were made available through Build Back Better legislation. Like Park East, that freeway was met with opposition and never completed, but also cut off and negatively impacted several neighborhoods.

“It took out a lot of businesses and homes and caused connectivity issues between the city and county,” Martin-Brown says.

Park has since moved on from Milwaukee. He became Denver’s City Planner before transitioning into his current role as adjunct professor at the University of Colorado, while working to update the city codes in places like Austin, Texas, and Sula, Montana. To Park, urban highways are a failed public experiment.

“There’s not a neighborhood that got improved or better when a freeway went through it,” he said. “Every single time that we take a freeway out of the city, whether in Seoul, Korea or the West Side Highway in New York or Park East in Milwaukee, things get better and the world didn’t end.”