“The right to have access to every building in the city by private motorcar in an age when everyone possesses such a vehicle is the right to destroy the city.” — Lewis Mumford, 1958

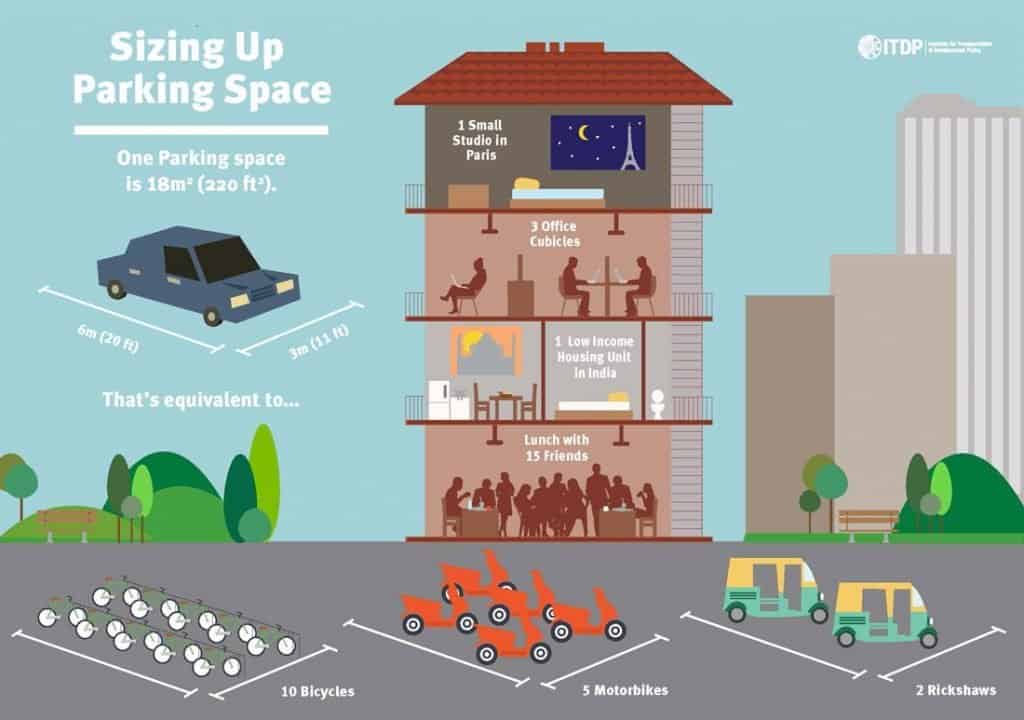

One of the unintended consequences of car-oriented cities is the sprawl created by cars that no one is driving. Parked vehicles take up an enormous amount of urban space. Yet parking is often seen as an inalienable right—both by the public and often in law—a perspective that has given us more congestion, pollution and sprawl, and less space for things like housing and transit.

Mexico City knows a thing or two about this. While the city has made strides in recent decades by developing an enviable bus rapid transit network and pedestrian-friendly streets, the metro area has sprawled uncontrollably. Between 1980 and 2010, the urban population of metro Mexico City doubled while the urban area increased by a factor of six. As a result, today many of the city’s 20 million residents live on the outskirts, enduring grinding commutes of four to six hours round-trip to reach their jobs in the city’s core.

But thanks to a landmark policy reform, things are beginning to change. In February 2017, the former mayor of Mexico City, Miguel Ángel Mancera, announced a plan to tackle the problem of sprawl with a major policy change aimed at reducing the number of parking spaces in the city.

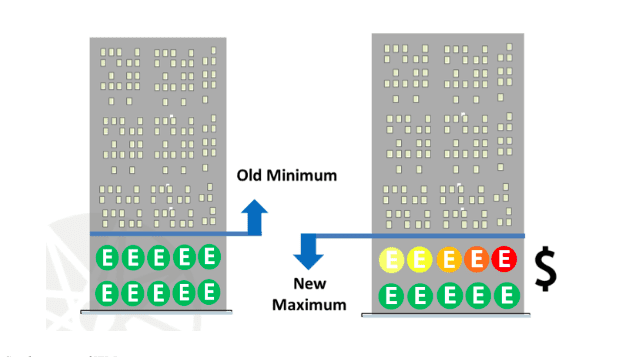

The new policy was announced on July 11, 2017. Called “limitation of parking spaces in the city construction code,” it reoriented the city’s previous approach by 180 degrees. Before, developers were required to include a minimum number of parking spaces in any new development, a vestige of an era when cars were ascendant and planners were fixated on allocating an abundance of space for them. Now, the city has flipped that illogical policy upside down, setting a maximum on the number of parking spaces that can be built in new developments.

Under the new law, a developer is limited to three parking spaces per unit of housing (no matter its size), and can build up to half of the maximum number of spaces allowed without penalty. If he wants to build more than half of the maximum allowed, a fee kicks in for each additional space—and increases exponentially as the number of spaces approaches the absolute max. The revenues raised from those fees is then poured into improvements in public transportation and subsidies for housing, creating a virtuous circle that disincentivizes driving and benefits transit.

It’s a groundbreaking approach to controlling sprawl, and positions Mexico City, the largest city in North America, as a leader in rethinking land use policies and prioritizing public space for people.

Getting it done took work—specifically, a decade-long campaign by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) called “Menos Cajones, Mas Ciudad” (Less Parking, More City). We worked in collaboration with the Ministry of Urban Development and Housing, the Ministry of Mobility and the Real Estate Association, among others.

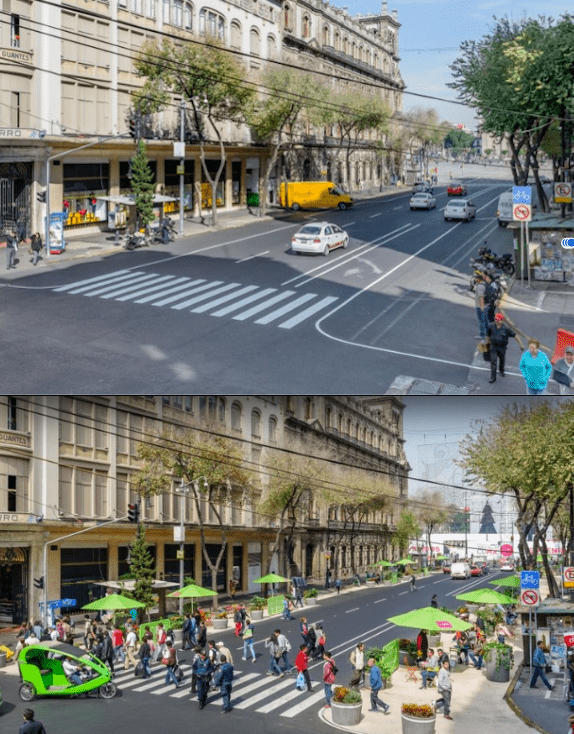

A key element of this campaign was proving to people that smarter parking regulation is worth it. To that end, in 2012 we helped implement Ecoparq, Mexico City’s on-street parking enforcement and pricing program. Before Ecoparq, loosely regulated parking resulted in chaotic streets with illegal parking, cruising, and a perceived scarcity of parking availability.

Neighborhoods that used Ecoparq such as Polanco saw the positive results of regulated parking, and the program has since expanded to nearby areas. Ecoparq helped prove that the city’s parking saturation was, in fact, simply a demand management problem—more free parking was encouraging more needless driving. This was the key that opened the door to the conversation about reforming off-street parking laws.

In 2014, ITDP released Less Parking, More City a study that gathered evidence of the city’s unsustainable parking trends. Incredibly, more space was being built for parking than for housing. In fact, the study found that more than 40 percent of Mexico City’s largest developments actually consist of space for parking, putting parking above any other land use in the city, including housing. The city was using prime, coveted land in the center of the city for parking structures, while people were forced to live on the city’s periphery because of a lack of affordable housing.

In addition, Mexico City’s supply of parking far outstripped demand, in part because of the minimum parking requirements. Developers knew their buildings didn’t necessarily need all that parking, but they were forced to build it. In the vast majority of cases, they would build as little as possible, and in the instances when they did exceed the minimum number of parking spaces, it was often because of constraints with the site. For example, a development requiring a minimum of 90 parking spaces might have three stories for parking, each with a capacity for 40 spaces, making it easier and cheaper for the developer to simply build 120 parking spaces.

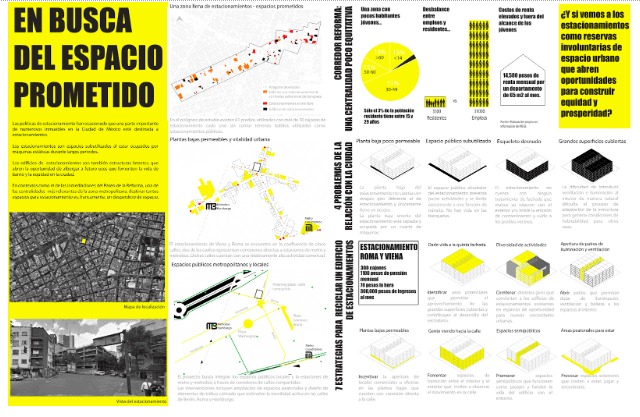

Once this evidence had been collected and best international practices explored, ITDP launched the Less Parking, More City public outreach campaign, bringing together a diverse group of agencies and actors to make policy reform happen. This collaboration made it possible for the message to be developed and broadcast to a wider audience. Interviews were set up with different stakeholders: opinion makers from media sources, real estate developers, city legislators, etc.

The outreach campaign included an open contest to reimagine parking lots for people, an idea from Juan E. Pardinas of the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness. With this contest curated by Ana Alvarez, we received the support of strategic allies coming from private companies, civil society organizations and a multidisciplinary jury of prestigious members: architects, urban planners, economists and public policy experts.

The list of supporters is long. This is what it takes to achieve major policy change. We got buy-in from the National Association of Supermarkets, Convenience and Departments Stores and also from the National Chamber of the Industry of Development and Promotion of Housing. With each of these partners, and with the help of Luis Zamorano from the City Ministry of Urban Development and Housing, we aimed for win-win arrangements. For example, some of them were concerned that the maximum number of parking spaces would be very low, so we designed a policy together that allowed them to still provide parking, just not as a mandatory condition as before.

The Local Legislative Assembly also recognized the need for policy reform, and the support of civil society was incredibly important. CoRe Foro Urbano, Bicitekas, WRI and editorial house Arquine were all key to creating this more powerful, cross-cutting and lasting public policy.

This policy shift is a huge win for Mexico City, placing it in the vanguard of sustainable and equitable urban development. Now it’s possible to build with or without parking depending on the market conditions. As the reform unfolds, ITDP will continue to work with the city and our partners to educate residents and support a shift to transit. We’ll measure the direct impacts with regards to enforcement, traffic reduction and the uses of this newly available space, advocating for affordable housing and improved public spaces. And as always, we will continue to improve the options of sustainable urban mobility, specifically mass transit—the backbone of any truly equitable city. I’m in for this ride.

This story is part of a collection called Pay for What You Get: Stories about paying for the true costs of how we use cities. Read more here.

A similar version of this story appeared on Reasons to be Cheerful on April 4, 2018.