The Zero Waste Center in Kamikatsu, Japan, looks like a peculiar kind of flea market: everything from metal ring pulls to plastic bottle lids, mirrors and thermometers are neatly stored in a row of yellow baskets.

The bric-a-brac of objects, far from being a disordered mess, have been carefully collected, sorted and deposited into 45 individual types of waste disposal containers by the town’s residents.

“Sorting waste into 45 different categories is much more difficult than you might imagine,”says Hiroshi Nakamura, the architect who designed and constructed the pioneering space, “but they are willing to do it.”

Built on the site of a former incinerator, the center has become the centerpiece of an ambitious goal: Kamikatsu’s effort to reuse or recycle everything it produces. In doing so, the town of less than 2,000 people, set on the Japanese island of Shikoku, has become a world-leading example of how a community can eliminate waste.

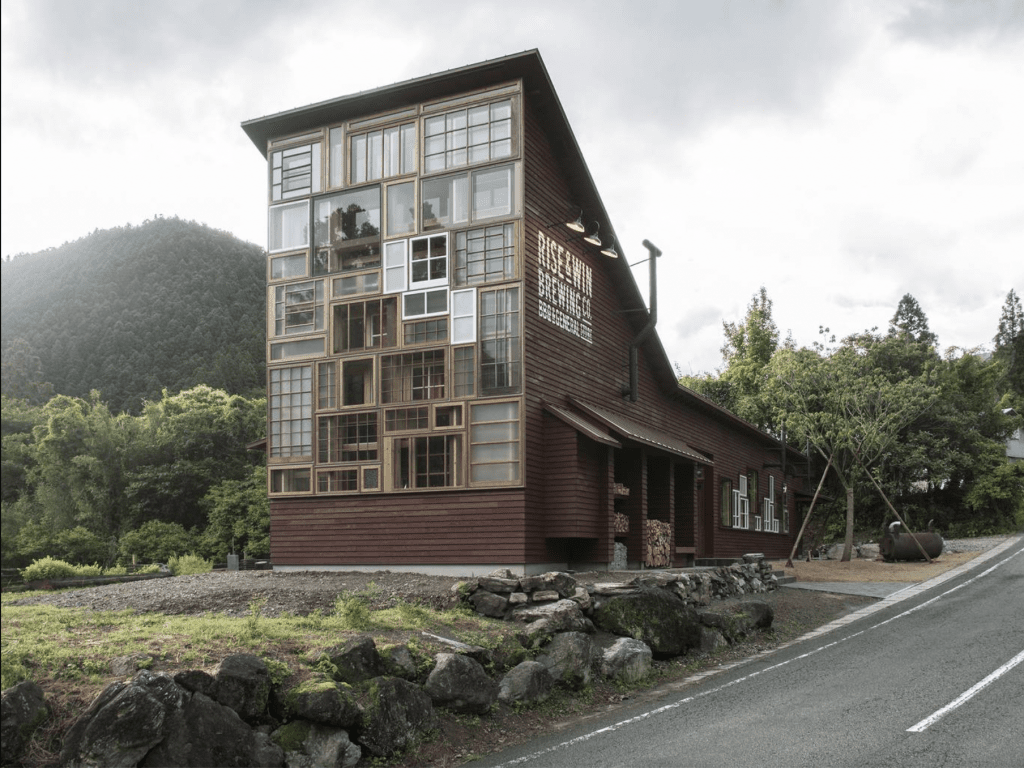

For starters, to earn “zero waste accreditation,” all of Kamikatsu’s businesses must adhere to a strict sustainability ethos that includes training employees on reducing waste and setting measurable goals. The Kuru-kuru store (a Japanese phrase meaning “to go round and round”) provides free second-hand items such as kitchen appliances and tableware, and sells old kimonos, bags and toys upcycled by local artisans. A brewery produces craft beer using yuko citrus peel provided by local farmers, and in turn receive spent grain from the brewery for compost. Cafe Polestar only serves organic local produce and offers discounts to customers who bring their own coffee cups. Hotel Why, which was built using local cedar wood as well as discarded doors and windows, welcomes tourists to experience the town’s zero-waste philosophy. Even the signs in the Zero Waste Center have been crafted from recycled materials.

“We wanted to create an architecture that would be in tune with their behavior and sensibility, always thinking and acting in ways that would allow them to reuse the waste instead of throwing it away,” says architect Nakamura, who also used spare mortar and ceramic pieces from flooring to make plastering material.

‘Turn garbage into a resource’

Kamikatsu’s target to eliminate waste without resorting to incinerators or landfills was set in 2003, when it launched the nonprofit Zero Waste Academy and became the first municipality in Japan to make a “Zero Waste” declaration. While the town has so far fallen short of that lofty goal, initially set for 2020, Kamikatsu recycled 81 percent of all its waste in 2020, according to Ministry of the Environment data, up from 58.6 percent in 2008, and much greater than Japan’s national average of 20 percent.

“It’s about how we can transform right now to have a sustainable life in the future,” says Akira Sakano, founder and director for Zero Waste Japan and former chair of Kamikatsu’s Zero Waste Academy. “We thought of developing Kamikatsu as a model and experiment for others to learn from and follow.”

Only very few kinds of waste are now incinerated — such as PVC and disposable diapers -- but even that is being addressed. Since 2017, Kamikatsu has been giving reusable “cloth diaper starter kits” to households with infants up to the age of one.

As a result, Kamikatsu has cut its spending on incineration by a third, and now brings in up to three million yen (around US$21,000) annually through selling recycled materials like paper or metals. Those earnings cover a very healthy proportion of the six million yen that goes towards waste management each year.

“I think Kamikatsu is a very special case,” says Misuzu Asari, associate professor at Kyoto University’s Graduate School of Global Environmental Studies. “Although the population is small, they were blessed with enthusiastic human resources and were able to effectively receive subsidies from the national government. It shows that if you do it thoroughly, you can ultimately turn garbage into a resource.”

The roots of Kamikatsu’s reuse revolution go back decades. During Japan’s postwar economic boom, the expansion of mass industry created huge amounts of waste, which increased from 6.2 million tons in 1955 to 43.9 million tons in 1980. In response, municipalities across Japan, including Kamikatsu, began to build incinerators to dispose of it all. But over time, concern grew about the pollution being created. “Kamikatsu’s transformation started because it couldn’t incinerate or send things to landfill anymore,” says Sakano. “There had to be a shift.”

That shift took years: In 1997, the town began recycling in nine different categories, and the next year that increased to 22. By 2001, Kamikatsu shut down its large incinerators and began recycling in 35 categories. It reached the current 45 categories in 2016, and the construction of the Zero Waste Center was completed in 2020.

Given that door-to-door collection would be costly -- Kamikatsu’s 55 hamlets are spread across a wide area dominated by forested mountains -- the town decided to require residents to drop off their waste at the center. Those who can’t make the trip, such as elderly residents, can organize pickups.

Initially, the implementation was met with resistance. For some residents, it was a struggle to prepare and sort trash: a plastic water bottle must be washed and stripped of its label and lid; glass must be separated by color; everything from thermometers to chopsticks and printer cartridges must be sorted. Yet over time, they were won over, in part thanks to the fact they are awarded points for recycling that can be exchanged for eco-friendly products. “It was tough because it changed their day-to-day duties,” says Sakano. “But people got used to it.”

Beyond promoting recycling, the program also encourages behavior changes. The town is working with local manufacturers to help reduce waste and advises residents to either avoid using single-use items, or, if necessary, buy products that can be disposed of easily. The sheer effort required to deal with trash, meanwhile, is seen as a deterrent for excessive consumption.

Customized recycling

Since 2020, Zero Waste Japan has focused on spreading eco-friendly policies to local governments across the country. Other Japanese towns such as Minamata in Kumamoto prefecture and Ikaruga in Nara prefecture are already on board.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Now Sakano is working in Obuse, a town in northwest Japan, helping the municipality to implement policies to reduce waste. For example, agriculture is a significant part of the local economy and through cultivating apples, chestnuts and pears, sometimes trees must be cut. While previously they were burned, the town is trialing the use of small-scale machines to create biochar, a soil enhancer that sequesters a high amount of carbon. “We try to customize the policies to each location,” she says.

According to Sakano, Zero Waste Japan, whose work is funded either directly by municipalities and businesses or through environmental partners, is necessary to scale up from Kamikatsu to all of Japan’s 1,700 municipalities. “The challenges in each place will be different,” she says. “I can’t go into every single one. But how to build the policy is the same: How can we reduce waste and circulate resources locally?”

These efforts overlap with the traditional Japanese concept of “mottainai,” which reprimands wastefulness and espouses respect for the world’s finite resources -- an ethos that has itself been upcycled for a modern era.

“We aim to spread a lifestyle that does not burden the global environment and build a sustainable society by empowering the circular economy,” says Akira Yamaguchi of the Mottainai Campaign, a project launched in 2005 promoting the philosophy as well as holding flea markets, symposiums and cleaning tours of Mount Fuji.

Professor Misuzu Asari says that nationwide progress has been made as recycling laws for individual products have been established, thermal recycling technology advances and waste sorting improves.

But there’s a long way to go. Japan, known for its hygiene-oriented culture of packaging, is the second highest packaging waste producer in the world, with its citizens using as many as 450 plastic shopping bags each year. Globally, plastic waste generation more than doubled between 2000 and 2019 to 353 million tons.

“Nowadays, there are still many things that are excessive, useless and disposable,” says Asari. “We need to change our mindset to reduce them. We must now steer toward the realization of a sustainable circular economy.”