A century ago, on a crisp fall day, the event that would change Japan’s approach to disaster preparedness occurred deep below the seabed of Sagami Bay. The massive earthquake radiated outward toward the cities of Tokyo and Yokohama, splintering their wooden buildings and sparking dozens of uncontrolled fires. Minutes later, a tsunami swept thousands of people from the peninsulas south of the capital. All in all, some 140,000 people perished in the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake.

The event was devastating, but it wasn’t unusual. As an island beset by earthquakes, fires, floods, nuclear meltdowns, volcanic eruptions, atomic destruction and deadly pandemics, Japan has learned to live with catastrophe. According to a 2013 study, the Tokyo-Yokohama metropolitan region is, by the numbers, the most disaster-prone place in the world.

Accordingly, Japan has spent decades preparing for the worst, and during this time, has developed a resilience to natural disasters that is unparalleled anywhere in the world. Its buildings are virtually earthquake-proof. It has the world’s densest seismometer network and the fastest earthquake warning system. Its tsunami alerts can detect a tidal wave within three minutes of its formation.

Some of Japan’s most unexpected preparations, however, can be found directly beneath the roots of its cherry blossom trees, hidden from view but ready to deploy at a moment’s notice. It’s a surprising innovation that combines two of Japan’s greatest strengths: disaster prevention and urban planning. And, like many things in Japan, it is one of a kind.

The park as a refuge

Japan’s efforts to integrate survival elements into its city planning began after the Great Kanto Earthquake revealed a flaw in its urban design. As destructive as the quake itself had been, the fires, fueled by ruptured gas mains and toppled cook stoves (which, at noontime, many were using to cook lunch) were even more devastating. “Streets, alleyways, bridges, rivers, canals and open spaces became virtually impossible to navigate” as the fires blocked people’s escape, according to one account. The combination of highly flammable wooden architecture and extreme density made the city a tinderbox with little to stop it from burning.

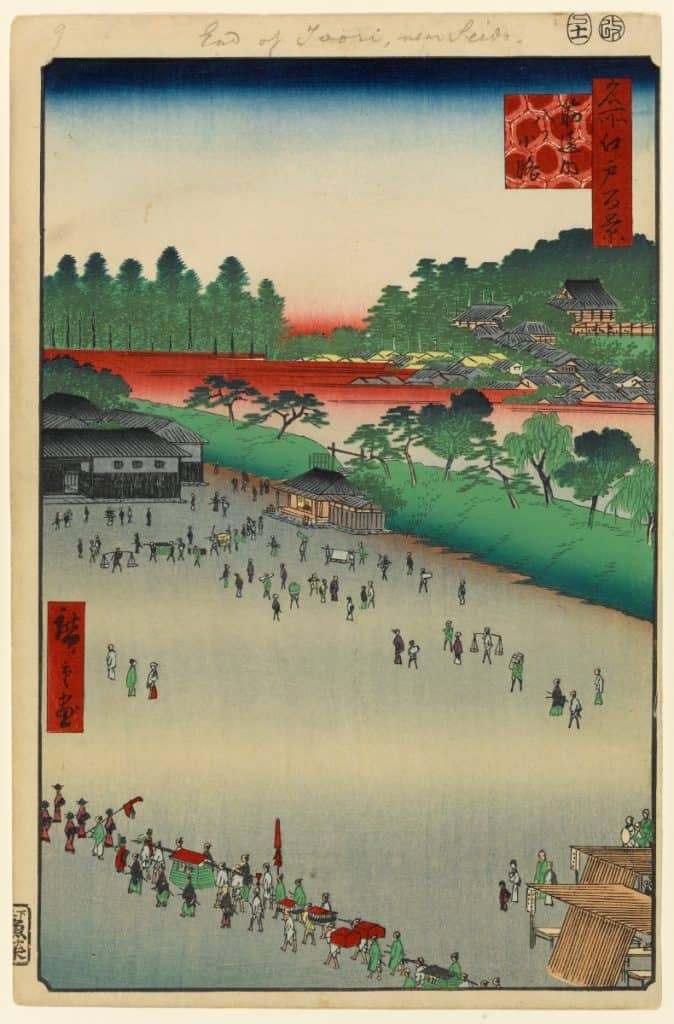

When the time to rebuild arrived, Tokyo’s planners realized the risk of urban fires could no longer be ignored. So they revived an urbanism concept from the Edo era called hiyokechi. These were plazas left unbuilt in crowded parts of the city to prevent fires from spreading and offer people a place to seek refuge during disasters.

Some hiyokechi became public parks, and in a handful of them, Tokyo’s distinct disaster preparedness measures are hidden in plain sight to this day. They are called “disaster parks” — over a dozen of them are scattered across the city. These are spaces that, in an emergency, can be quickly converted into survival camps. Many are idyllic landscapes that, on any given day, attract crowds simply looking for respite. One of these is Hikarigaoka Park, a 150-acre expanse of cherry blossom trees, ponds and tennis courts.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.What you’d never notice about Hikarigaoka Park, however, is that 36 of its benches conceal stoves that can be used to cook food, boil water or provide heat. The park’s 52 manhole lids can be removed to reveal emergency toilets. Its solar-powered lamp posts have electrical outlets for charging phones in a blackout. There are water tanks for fighting fires, and bunkers stocked with days’ worth of non-perishable food.

Introducing the Kamado Bench at a #DisasterPrevention Event at Yoyogi Park. Benches can be used as stoves for cooking in an emergency. #TT pic.twitter.com/NzXt9eb7p6

— Tokyo Gov (@Tokyo_gov) March 14, 2017

Over a dozen of these disaster parks are scattered across the metropolitan region. Their coordinating hub is the Tokyo Rinkai Disaster Prevention Park, a 33-acre green area in the seaside district of Ariake. In addition to space, Rinkai contains a heliport and a large command center. Here, Tokyo’s disaster response teams converge in an emergency to collect information, coordinate aid units and act as a center for medical care.

Rinkai also has a two-story facility in which visitors can learn about disaster preparedness. At its theme park-like “experience center,” visitors begin their journey by entering an elevator. Suddenly, it shudders and goes dark. The doors open to reveal a streetscape badly damaged by an earthquake — collapsed buildings, fallen electrical wires, crushed cars. As they make their way through, visitors are guided through this cataclysmic realm by a tablet that quizzes them along the way. They learn to turn plastic sheeting into drinking cups and fashion garbage bags into rain gear.

It’s a uniquely Japanese experience emblematic of a country accustomed to living with threats. Japanese people are often seen as a nation of rule-followers, but when it comes to disaster, they tend toward communal self-sufficiency, looking to each other — as opposed to the government — for cues on how to react, writes David Pilling in his book Bending Adversity: Japan and the Art of Survival.

“In many ways, they show a pioneering spirit more reminiscent of the rugged American West than the uniformity and dependence on top-down authority sometimes mistakenly associated with Japan,” he writes. Pilling notes that after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami that ravaged Sendai, ordinary residents went ahead and began rebuilding the city themselves.

This mindset is emblematic of a country that views disaster parks as an appropriate crisis countermeasure — an available tool that resourceful citizens can leverage themselves. It also helps to explain Japan’s casual response to the Covid-19 pandemic. As countries around it quickly implemented strict measures of tracking and control, Japan’s government has demonstrated a relatively hands-off approach. Residents have continued to commute to work, visit relatives and attend the country’s cherry blossom festivals. When asked why the city wasn’t discouraging residents from seeing the cherry blossoms, Tokyo’s governor said that to do so “would be like taking hugs away from the Italians.” But, in its struggle to survive, Italy has taken hugs away. Time will tell whether Japan’s approach should have followed suit.