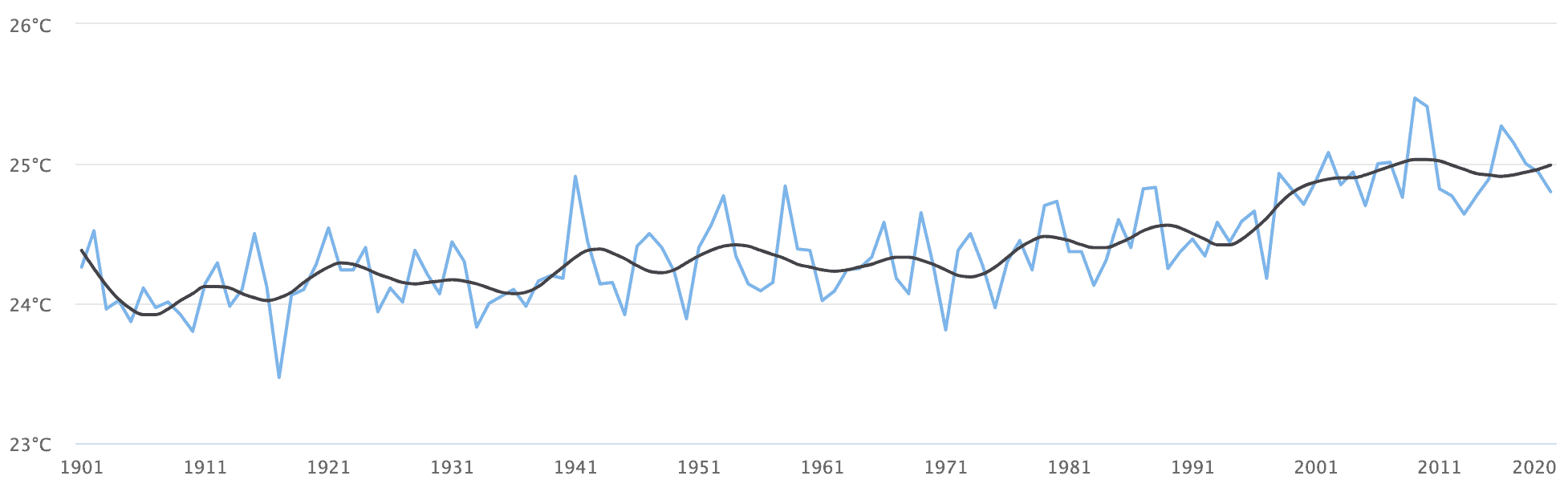

During the scorching midday heat in Behrampura, a slum in the Indian city of Ahmedabad, it can be difficult to breathe, let alone get any work done. Throughout the summer, peak daytime temperatures often exceed 38C (100F). Crowded and cramped housing, a lack of ventilation and the prevalence of cheap, heat-trapping materials such as metal roofs magnify that heat to even more unbearable levels.

“The heat has been going up and up,” says Dilshadbanu Mohammed Jhilani Shaikh, a mother of four living in a shack in Behrampura. “It gets so bad that you just can’t do anything, not even move. You’re so drained of energy.”

On May 19, 2016, Ahmedabad recorded a maximum temperature of 48.4C (119F), its hottest day in a century. That year, Shaikh decided to take action against the heat. She invested 120,000 rupees (USD$1,584) — a significant sum which she borrowed from a friend — in a cool-roof technology module, installing it with the support of Mahila Housing SEWA Trust (MHST), an Indian nonprofit that works with collectives of grassroots women in the informal sector to improve their housing, living and working environments.

The roofs can help prevent heat-related deaths, a major problem in places like India — during that 2016 heatwave, dozens of deaths were reported by the city’s hospitals. But they can also combat a less visible, more pernicious effect: the slow-burn impact of extreme heat that leaves people tired, sick and sleepless, making it harder for them to study or work. The International Labor Organization projects that India will lose the equivalent of 34 million full-time jobs in 2030 due to heat stress alone.

Tasked with domestic chores and often earning their income from home, women living in informal settlements are particularly susceptible to this type of heat-related stress. A study conducted by MHST found that increased indoor temperatures severely affect women home-based workers, with their productivity falling by up to 50 percent in summer, reducing their income. But since informal housing is rarely subject to planning regulations and conventional air conditioning is expensive, systemic and scalable solutions can be hard to implement.

Lower temps, higher earnings

For Shaikh, who handmakes kites to sell during Ahmedabad’s famed annual festival, having a cooler place to work at home is essential. (Her husband, an electrician, is out of the house most of the day.) But since the new roof was installed — a modular unit made from packaging and agricultural waste — daily temperatures in the house have on average been 4C to 5C cooler. That means her potential workday has been extended by a couple of hours, increasing the number of kites she makes. “My quality of life is better,” she says. “But it’s also much better economically. That investment has already earned itself back.”

The roof has sheltered Shaikh’s family in other ways, too. Climate change has brought not only hotter temperatures, but also more intense monsoons during the rainy season. Before, that meant Shaikh’s kites, which are stored at her home, could be damaged if the roof was breached. “I had a constant fear that the water would drop,” she says. Now, with the reinforcements, there’s no longer any leakage during heavy rains.

Other women surveyed by MHST have reported saving money on electricity bills through reduced use of fans, being able to continue working during the peak heat hours of 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. and that their children are able to study at home with better concentration.

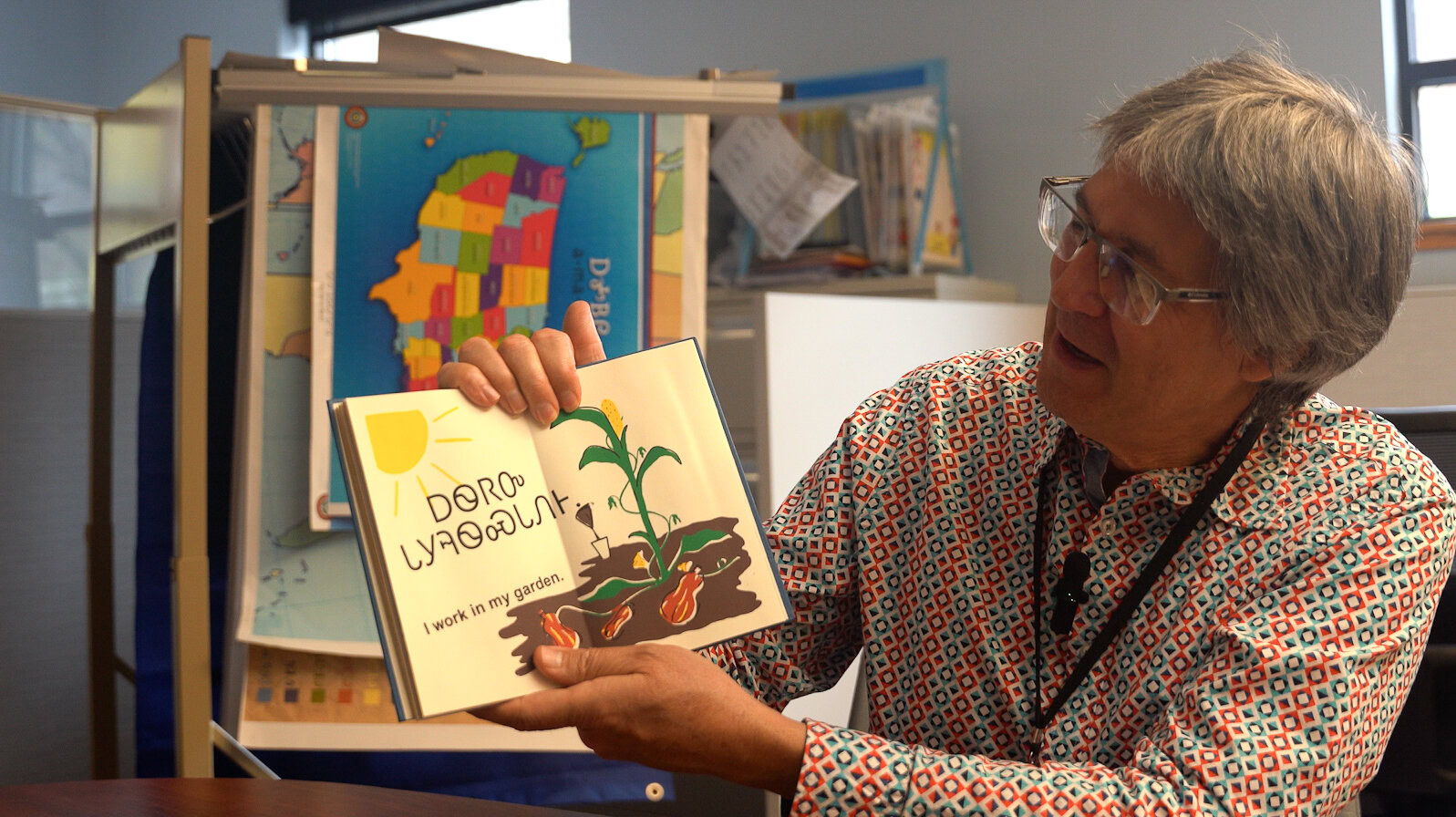

MHST is working in seven cities across India — including Rajasthan, New Delhi and Jaipur — to help women like Shaikh tackle heat stress in their homes. More than 27,000 households across 1,066 slum settlements have been supported in installing sustainable cooling technologies. Among the suite of technologies are modular roofs like Shaikh’s, which are easy to install, construct and replace; solar reflective white paint, which effectively reduces heat absorption (and is also being used on the streets of Los Angeles); and resin-coated bamboo mats that form strong, lightweight, weather-resistant panels.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.“Most people use tarpaulin, metal sheets in their houses,” says Pranita Sinha of MHST. “There’s a lack of ventilation. It’s a tough situation. But these tools help cool them right down, in ways that fit with their living environment.”

The nonprofit has taken an “holistic,” gender-sensitive approach, consulting women from affected communities, as well as local government officials, scientists, engineers and architects. “We are a women-based organization,” adds Sinha. “Women living in informal settlements are often overlooked. We want to change that and prioritize them. But we have to build trust and consult them. When they trust you, they give you permission to do anything.”

With growing health risks from rising temperatures, the lack of essential indoor cooling is becoming a deadly threat. Almost 500,000 people die each year due to extreme heat, according to a study published in July in The Lancet. A separate study published in 2019 estimated that 1.8 to 4.1 billion people, mostly in India, Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, are vulnerable to heat stress and lack access to technology to cool living spaces.

“It’s a very serious issue in India,” says Narasimha Rao, co-author of the study and associate professor of energy systems at Yale University. “A lot of these people live in conditions that don’t protect them from heat. They live in cities where there’s an urban heating effect. These are the worst possible conditions. Every day people are dying.”

Rao believes MHST’s focus on improving the informal housing structures could have a powerful and immediate impact. “It’s most important because the roof is usually of the poorest quality,” he says. “These are extremely important in the short term, because you don’t have to move them from their homes.”

However, he argues that in the coming decades residential buildings in India need to be completely upgraded. “If we’re thinking about the longer term, we have to create better housing structures,” he says. “Origin of services such as sanitation must be improved, and overcrowding, especially in urban areas, must be reduced.”

In the meantime, MHST is trying to broaden its reach and make access to the tech more equitable. Some women can’t afford to invest in these technologies, according to Sinha, and so the nonprofit is developing a project on the world’s first “heat insurance,” which could financially secure the livelihoods of women suffering heat stress. “Good health and independence is the least that they deserve,” she says.