When Karen Byskov Lindberg bought a house in Oslo in 2018, she set about a refurbishment that would drastically transform her energy consumption.

After removing the house’s old oil boiler system, she installed improved wall insulation, new window fittings, an air recovery system and, importantly, a heat pump. As a result, she says the structure’s average energy use has dropped from 35,000 kilowatt hours (kWh) per year to just 8,500 kWh – less than a quarter of what it was before.

“The energy use is extremely low,” says Lindberg, who is a 43-year-old university professor in the Norwegian capital. “It’s economically beneficial but also it reduces CO2 emissions.”

Like Lindberg, millions in Norway and across Europe are increasingly turning to heat pumps as a hyper-efficient, eco-friendly way to warm their homes. According to data from the European Heat Pump Association (EHPA), nearly 15 million households in Europe had heat pumps in 2020, up 7.4 percent from the year before.

But Norway is by far the leader of the pack. With 1.4 million units, it has 604 heat pumps installed for every 1,000 households. The next closest are Sweden with 427 per 1,000 and Finland with 408 per 1,000.

Heat pumps began appearing in Norway after the oil crisis of the 1970s, according to Rolf Iver Mytting Hagemoen, secretary general of the Norwegian Heat Pump Association, when a government-funded program to encourage their use was established. Yet for years they remained relatively niche, he says, with less than 10,000 heat pumps installed by 2005.

But Norway’s embrace of heat pumps eventually arrived, fueled by government subsidies, high fossil fuel taxes, low electricity rates and restrictions on oil boilers (which have been banned since 2020). “There was initially slow growth in heat pumps in households since 2000,” says Hagemoen. “But Norway was an early mover in the market. It’s now the leading country in Europe.”

While heat pumps are yet to become widespread globally, Hagemoen says they offer several benefits compared with traditional heating. Low maintenance and cheap to run, they work as both a heating and cooling system, and have a very efficient conversion rate of energy to heat. They’re also light on emissions if the electricity used is renewable. “If you want to be independent of gas, you need other solutions,” says Hagemoen. “And when it comes to electricity, heat pumps are hard to beat.”

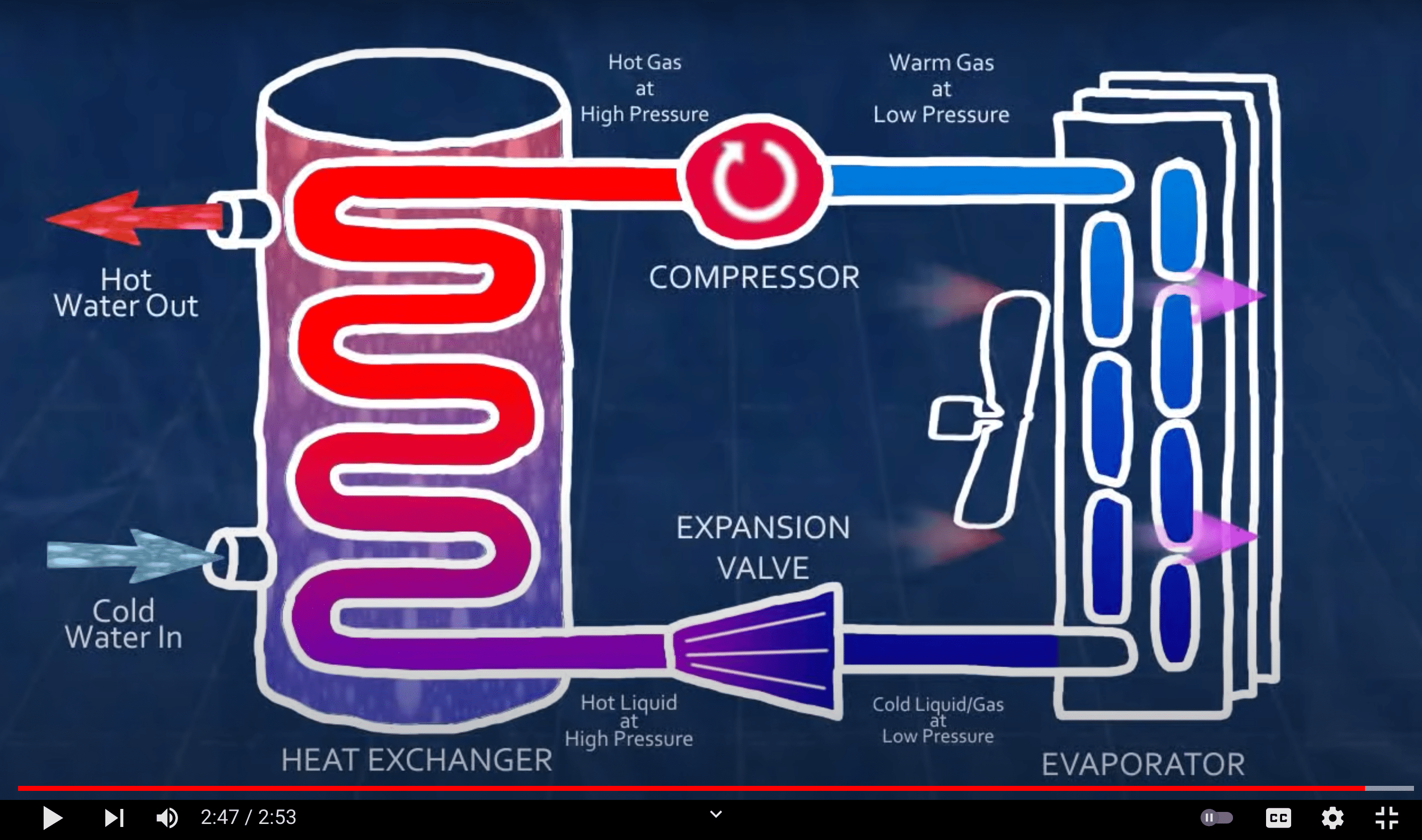

Heat pumps, which can operate at external temperatures of -25C (-13F) and provide hot water at 65C (149F), come in several forms. The most common is the air-to-air pump, which looks similar to an air conditioning unit. It sucks in air and distributes it over a system of tubes filled with a refrigerant liquid, which warms and turns into a gas. The pump compresses the gas back into a liquid to release the stored heat, which is spread through radiators or underfloor heating, working like a refrigerator in reverse.

Nick Eyre, professor of energy and climate policy at the University of Oxford and director of the Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions, says that heat pumps are one of the most effective options to decarbonize heating systems.

“Hydrogen is an option, but it’s some way off [from large-scale use],” he says. “In some countries, such as in Scandinavia, there’s biomass. But when it comes to electricity-powered energy, the heat pump is much more efficient.”

In most developed countries with temperate climates, about 30 to 40 percent of household energy consumption is used for heating, according to Eyre. “It’s a serious problem and it does need to be solved,” he says.

One issue, however, is that in some countries demand for energy is “strongly winter-peaked.” That can mean huge seasonal strains on the network. “In a climate like the UK, we basically use very little space heating for six months of the year,” he says. “In the other six months, there’s a big variation.”

Four times as much energy can be used at peak times when compared to a normal day –0 far more than current infrastructure would allow for. “The amount of electricity capacity and stations you would need would be very large, implausibly large,” he says. “That’s a conundrum for decarbonizing heating. That’s the long-term challenge, the generating capacity and the wires in the ground.”

Another obstacle is the upfront cost. According to Hagemoen, while air-to-air systems are the cheapest option at around €1,500 to €3,000 (USD $1,700 to $3,400), air to water heat pumps can cost up to €15,000, and geothermal systems, the most efficient, can cost over €25,000. At the same time, gas boilers remain very cheap in many European countries. “Most people are more interested in the investment costs,” he says. “So for the moment you need subsidy schemes and building regulations for people to choose heat pumps.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.But Lindberg says that while her initial investment of 2.3 million krone ($250,000) for the complete refurbishment is expensive, it will pay for itself in the long term, while being much better for the environment. “The reason people don’t invest in geothermal heating is because it’s expensive,” she says. “But the gains you make are through the lifetime of the investment. The house will stand for the next 60 years.”

As it stands, only six percent of Europe’s 244 million residential buildings have heat pumps installed, according to the EHPA. While the European Commission aims to phase out fossil fuels in heating and cooling by 2040, that means 40 percent of residential and 65 percent of commercial buildings will need to be heated with electricity by 2030. To achieve those goals, the EHPA estimates the number of heat pumps in use will need to increase to 50 million.

Meanwhile, technological advances could see heat pump use expand beyond households and into industry. Norway is developing a heat pump that can produce temperatures of up to 180C (356F), and according to research by Sintef Energy Research, the Norwegian University of Science & Technology, and industrial partner ToCircle, the technology could allow a fifth of all European industry to cut its energy use by 70 percent.

“As the technology gets more popular across Europe it will get cheaper and cheaper, just like solar panels have,” says Hagemoen. “It is the technology of the future.”