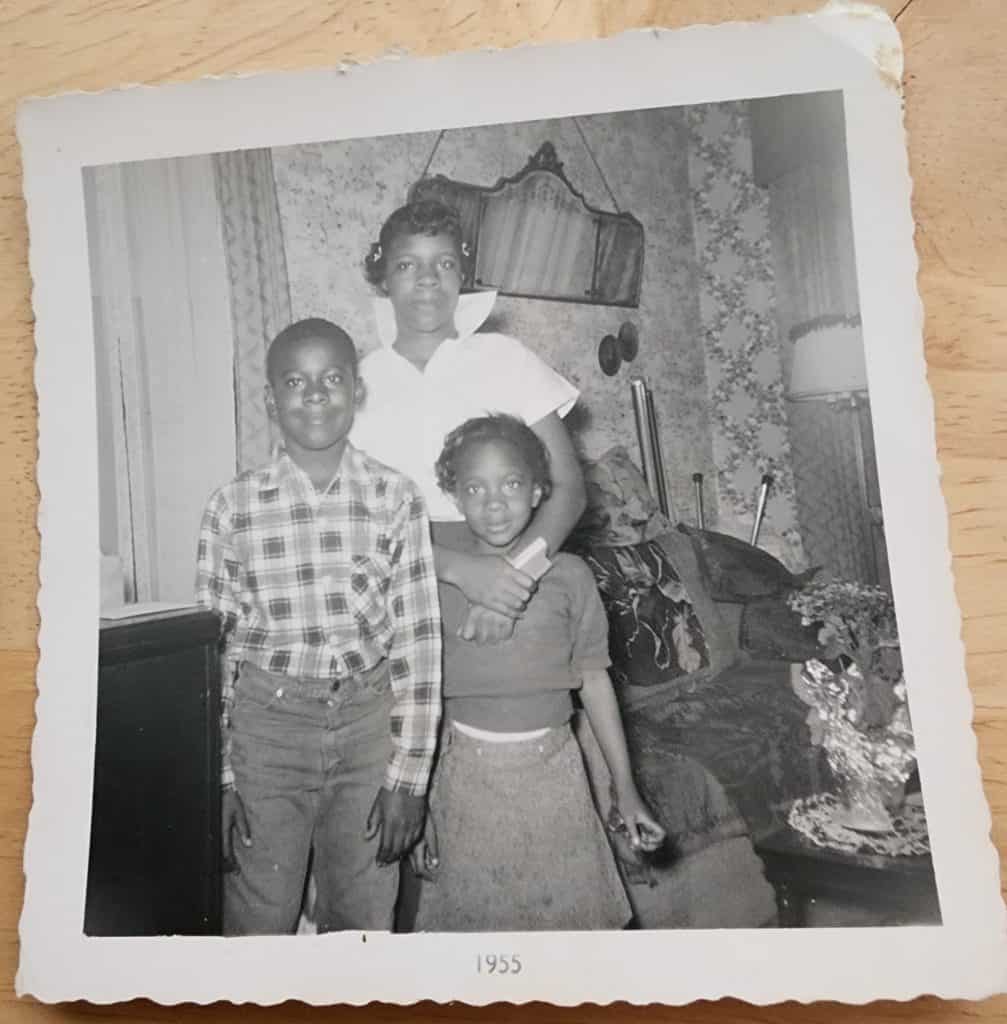

For most of her childhood, Ramona Burton didn’t notice other people treating her differently. Born in the city of Evanston, Illinois, the 73-year-old was raised by hard-working, loving parents: her mother was a primary school teacher; her father, among several jobs, was an employee at the Oscar Mayer meat company.

But as Burton grew up, she began to connect the dots. One time, she remembers, the family ordered a meal at a restaurant but they were told they could only have take out, not eat the food inside. Then, as a high school student, she was suspended for a day or two just for running down the hall too quickly, something that never happened to white students. Later on, she found out that she and her siblings had to be delivered in a Chicago hospital — Black babies weren’t allowed to be born in Evanston’s. “I realized there was a different set of rules for caucasians and for Blacks,” she says.

That prejudice against the Black community was deeply entrenched across the country as Burton grew up. Some say that while aspects of equality have improved and discrimination has reduced, much of it remains. But in a pioneering effort to begin the healing process for decades of racial injustice, last year Evanston became the first city in the US to offer Black residents reparations.

“We hope this will lay the tracks and foundations for a better future,” says Peter Braithwaite, 2nd Ward Councilmember and Chair of the City’s Reparations Committee. “But there’s a long way to go. This process will take generations.”

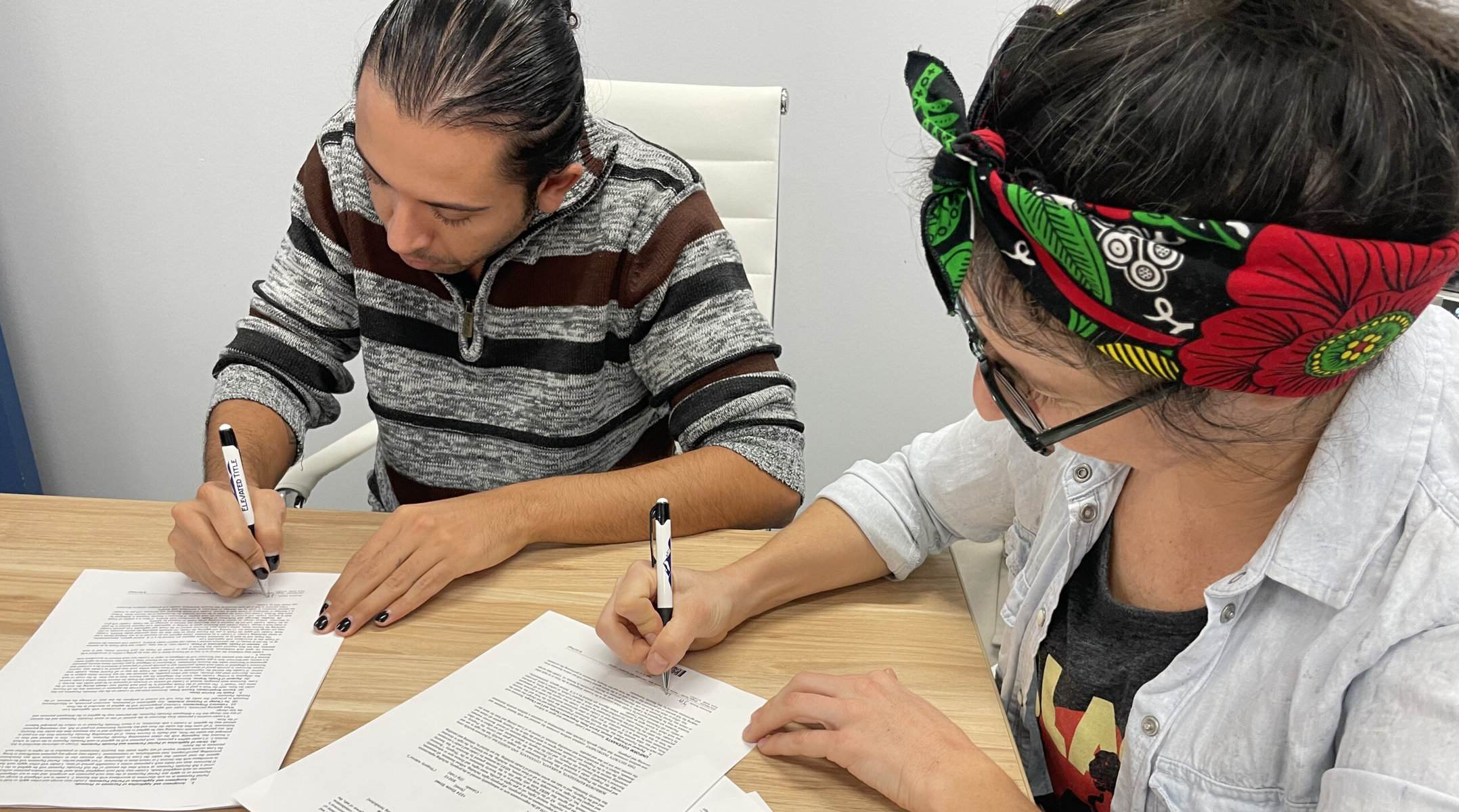

Under the “Restorative Housing Program,” the first of the reparations initiatives, Evanston City Council has given an initial 16 qualifying Black households $25,000 for home repairs, down payments or mortgage payments. In order to qualify, residents must either have lived in — or be a direct descendant of a Black person who lived in — Evanston between 1919 to 1969 and suffered a form of discrimination related to housing because of city ordinances, policies or practices.

Research commissioned by the City of Evanston, which formed the groundwork for the reparations policy, uncovered city-mandated housing discrimination during that period. This included arbitrarily denying Black communities loans in a practice known as redlining, demolishing Black homes through commercial rezoning, and divesting from Black communities by closing the only school and hospital. These actions “led to the decline of socioeconomic status and hindered the ability to acquire wealth for Evanston’s Black community,” the researchers found.

The relics of those discriminatory policies are stark: Since the 1960s, unemployment in the city’s Black community has risen from five to 15 percent even while the citywide average has held steady below eight percent. Median income in the 5th ward, a Black neighborhood, ranges from $45,000 to $55,000, while the median in Evanston is between $60,000 and $110,000. The ward also has the lowest property values in the city, no public school, and is the only ward with areas classified as food deserts.

In response to those findings, the city identified four areas in which its local reparations could be focused: housing, education, economic development and mental health support related to the traumas of discrimination.

The first to be addressed is housing. The city is funding the scheme through a three percent tax on the sale of recreational marijuana from a local dispensary, as well as through private donations from individuals and companies. The goal is to “revitalize, preserve and stabilize” homes; increase homeownership and build wealth; build intergenerational equity; and improve the retention rate of homeowners.

Cornell William Brooks, professor of the Practice of Public Leadership and Social Justice at the Harvard Kennedy School and a reparations advocate, believes the policy has the potential to be a landmark moment in US history.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.“It is a first step, but it is an extraordinarily commendable first step,” he says. “The first government reparation check was not issued by Washington DC. The cradle of the confederacy, Richmond, Virginia, didn’t do it. Charleston, South Carolina, where the Civil War began, didn’t do it. What this midsize city in Illinois is doing, attempting to repair the harm born of slavery, is not just noteworthy, but historic.”

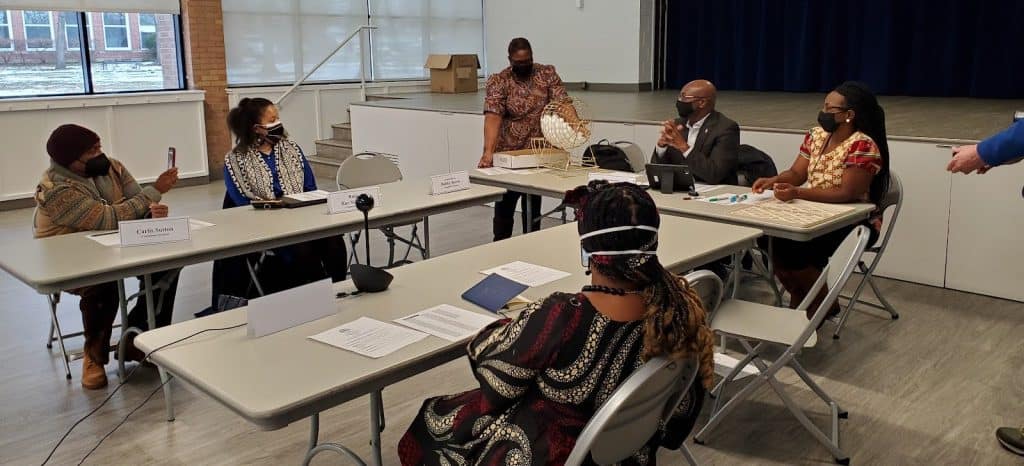

The development of Evanston’s reparations dates back years and is rooted in community engagement. The Equity and Empowerment Commission held two meetings in July 2019 to discuss practical solutions for reparations with community members. Then, in November 2019, the council adopted Resolution 126-R-19, establishing the Reparations Fund and the Reparations Subcommittee. Following that, the subcommittee hosted three town halls to educate and inform the community on reparations at the local and federal level, plus 15 public meetings to discuss the Restorative Housing Program. “It helped us not only improve the program, but, I believe, contribute to the national discussion,” says Braithwaite.

While pioneering, Evanston’s scheme forms part of a wider national movement for reparations. Amherst, Massachusetts; Asheville, North Carolina; and Iowa City, Iowa, are among the places to have stated an interest in launching their own initiatives. And at the federal level, legislation has been introduced to create a commission to study and develop reparations proposals for Black Americans. Yet the issue is divisive: An opinion poll released in 2020 found that 80 percent of Black Americans believed the federal government should compensate the descendants of enslaved people, while only 21 percent of white respondents agreed.

According to data from 2019, the median white household held $188,200 in wealth — 7.8 times that of the typical Black household. Experts say that gap, which adds up to $14 trillion according to some estimates, can be linked to centuries of slavery, mass incarceration, discriminatory housing and finance policies.

“We’re talking about not billions but trillions of a wealth gap,” says Professor Brooks. “These inequities, perpetuated inequalities, are felt in your pocket book and in your DNA — in other words, people have less money, less worth and less life.”

That’s why Brooks believes the evidence-based nature of Evanston’s approach is crucial — and in that sense can be applied at the federal level. “Evanston engaged the community, it formed a commission, used scholars and research, was empirically driven and narratively informed,” he says. “This is a useful model. When you compare Evanston to the federal level, it’s like comparing a minnow to a whale. That being said, the minnow makes a case, a municipal argument for the federal response. It’s like the Montgomery Boycott to the Civil Rights movement.”

Others have also endorsed Evanston’s Restorative Housing Program, such as The National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America and the National African American Reparations Commission. But the scheme has its critics, who say it is far from the direct payments that have come to characterize the idea of reparations, a form of redress for slavery and the subsequent racial discrimination in the United States.

Cicely Fleming, a Black alderwoman whose roots in Evanston go back to the 1900s, released a statement saying that while she is in support of reparations, she believes the Evanston scheme limits participation and fails to provide enough autonomy to the community that has been harmed. Whereas direct cash payments with no strings, she argues, allow community members to decide what’s best for themselves, Evanston’s payments must be spent in ways predetermined by the program.

But, according to Braithwaite, the reality is not so simple. For one, the city does not have the authority to exempt direct payments from state or federal income taxes, meaning recipients of any such stipends would be liable for the tax burden — as much as 28 percent. And the practicalities of awarding funds means that housing is the most straightforward method. A report on the city’s policies identified housing as the “strongest case for reparations” and uncovered “sufficient evidence” of discrimination as a result of city zoning ordinances in place between 1919 and 1969. “Housing was at the top of the list of needs for the Black community, one of the top strategies for city council, and discrimination of housing is identified as one of the foundations of harm for reparations,” says Braithwaite.

Early evidence of Evanston’s program has shown tentative success. 122 out of around 700 Black households have already had their applications approved.

Recipients of the housing reparations are pleased with the work, too. Ramona Burton, a widow who has lived in her current home for 46 years, is one of the first recipients. She is using the money to replace her roof, install new windows and build a fence around her backyard. “I was very happy when I heard,” she says. “I never thought that I would be picked. It was like a cherry on a Sunday.”

But long-term indicators will prove more reliable: the city will monitor property values, the extent of segregation, the number of properties successfully being transferred through generations, as well as broadly the education and health outcomes of the city’s Black community.

In the future, Evanston plans to expand its reparations to other realms like education — a school will be restored in the 5th ward to replace the one torn down before. The city is also sharing best practices with a number of other cities such as Providence, Rhode Island and San Diego California, while in conversation with the National League of Cities. “Each local municipality has a specific harm depending on local history,” says Braithwaite. “But there are learnings we can share.”

Yet Braithwaite is clear about the limits of the program’s objectives. For one, Evanston’s reparations are only responding to the local wrongs that were done, not those perpetrated on the federal level. “These local reparations are much different to the national issue,” he says. “The foundation of it is what was done against the Black community in Evanston.”

Burton agrees that these reparations can only achieve so much, but that they should nonetheless be scaled. “I think it’s a baby step in the right direction,” she says. “It’s kind of like an apology for wrongdoings and it is helping out. I think every major city should join, especially down south, where prejudice was well known.”

One teething problem, however, is financing. With just one cannabis dispensary, Evanston’s initial income for the scheme has been lower than expected — though there’s capacity for up to five dispensaries to be built. Other proposals reportedly being considered include a tax on lakefront properties and a transfer of $5 million from the city’s general fund. “I hope that we’re able to attract more dollars and accelerate this program to fund all those who applied,” says Braithwaite.

But advocates say that reversing decades of racial discrimination, done well, will be a gradual process. “We need to manage expectations, but also need to be sure that monies are being justly spent,” says Brooks. “Assessment is so important here. Are we doing what needs to be done in a demonstrably impactful way? We can’t look at the long arc of history and insist on solving the problem in nanoseconds.”