In the ‘60s I lived in Baltimore and my parents would take me with them when they went to visit their families in Scotland. The buildings in Glasgow then were all black, covered in coal soot. Now it’s been sandblasted off to reveal the lovely red sandstone underneath.

We stayed at my grandparents semi-detached. I loved watching the coal fire that heated the house, but didn’t like so much the ritual of getting up in the cold mornings and restarting it. The whole city smelled like coal. I loved this smell, and recognized the smell again when I made a short visit to East Berlin years before the wall came down.

Coal was the principal energy source in those days, and had been for over 200 years. It is the largest contributor to man-made climate change. In 2019, 40 percent of carbon dioxide emissions globally came from coal. That doesn’t even account for the mercury, lead and sulfur dioxide that goes into the air when coal is burnt. Those are all killers, too, but it’s the carbon dioxide that is irreversible — and that will make large parts of the Earth uninhabitable. The externality, the true cost, of the Industrial Revolution might be irreparable and unimaginable damage to the whole planet. And there’s no Planet B.

Some countries are releasing more CO2 than ever, particularly those with fast-growing economies like China, which was responsible for the vast majority of last year’s growth in global emissions. But many others are turning away from the dirtiest energy source in the world. Last year, coal emissions globally declined unexpectedly by about one percent, driven, in large part, by sharp reductions in coal use in Europe. European nations are pulling the plug on coal, and an end to coal power is in sight, or at least possible.

Holland

Holland, aiming to make its electricity production carbon neutral by 2050, is phasing out most of its coal power. Interestingly, this is partly in response to legal action.

An organization called Urgenda (a bit like the National Resources Defense Council or Client Earth) sued the Dutch government in 2013 for endangering the lives of its citizens by allowing carbon emissions that contribute to climate change. Urgenda won, and now coal power there is being scaled back, as is cattle and pig farming and other polluting industries. The country’s major coal plants are being forced to reduce their capacity by at least 75 percent. Their effort sets a legal precedent that many other countries are looking at. A group of young people in Colombia is using this tactic to stop deforestation of the jungle in that country

Germany

Germany closed its last coal mine on December 21, 2018 and plans to shut all of its coal power stations by 2038.

As locally mined black coal became more expensive than coal from less regulated countries in recent years, closing German mines became a bit of a no brainer. And though it might be a good start, simply switching to unethically mined foreign coal, which is what they did, doesn’t really solve the problem. Getting off coal as a power source will take a bit longer, but the country remains committed as it works to meet its obligations under the Paris climate accords. Germany aims to be completely carbon neutral by 2050.

Austria

Austria closed its last coal power plant in April. It plans to turn off its last gas-fed power plant by 2030 and switch to 100 percent renewable sources. Wow, not just coal but all fossil fuels! To become an all-renewables nation, however, some argue it will need to get the public to sign off on more dams — since much of Austria’s renewable energy is generated from hydropower — and that could be a tough sell. Dams have their own problems with silt and wildlife.

Sweden

Sweden closed its last coal power plant in April, just after Austria did the same — two years ahead of its own self-imposed deadline. The early closure was made possible by a mild winter that reduced power demand. When it shut down, the energy firm that owns it, Stockholm Exergi, announced that the closure would reduce the company’s total CO2 emissions by half, and that its goal was to transition to an all-green energy profile.

Belgium

Belgium shut down its last coal power station, Langerlo, on March 30, 2016. This marked the end of a long process in Belgium. Coal has been crucial to the country’s economy for centuries, so much so that when Belgium declared independence from the Netherlands in 1831 its separatists cited “rich supplies of coal” as proof that Belgians could make it on their own.

Though Belgium started shutting down coal plants in the ‘80s, as recently as 1994 coal accounted for 27 percent of the country’s energy mix. Oddly, in 2007, the energy company E.ON announced plans to build a new coal plant in Antwerp, but there were loud public protests and in 2009 the government denied the permits.

France

France will be coal-free by 2021. It closed its last mine in 2004, the first large country to do so. But some power plants are still operating using imported coal, which is a fraction of the price of French coal, hence the closing of the French mines.

In January 2018 at the World Economic Forum in Davos, President Emmanuel Macron announced that he would speed up a phase-out process begun by the previous president, Francois Holland, who had promised to get off coal by 2023. France only gets one percent of its energy from coal now, so this virtue signaling Macron did at Davos was hardly radical, but it does set a good precedent.

Portugal

In 2018 Portugal began reducing tax exemptions for coal power (they got tax exemptions!?) and their environmental minister now says that the last of the country’s coal plants will close by 2030. They hope to be carbon neutral by 2050 by switching mainly to solar — a goal that Portugal has shown promise of hitting. In 2018, some 55 percent of its energy came from renewable sources, and in April the government announced plans for a solar-powered green hydrogen production plant as part of its Covid-19 economic recovery.

United Kingdom

In February, Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that the U.K. will end the use of coal power in 2024, a year earlier than anticipated. (It’s on a trajectory to be close to zero by then anyway.) Already, all but four of the country’s coal power plants have shut down in anticipation of the ban, and coal now makes up only two percent of its total power mix, down from nearly a quarter four years ago. The closures are a reflection of Britain’s broader transition to green energy. Since 2012, the “carbon intensity” of its grid — the measure of how much CO2 it must create to produce energy — has fallen by over two-thirds.

Italy

In an announcement widely celebrated as great news for the climate, Italy’s economic development minister confirmed that his country is committed to phasing out coal by 2025. However, the government has yet to reveal its strategy for meeting this commitment.

Several other European countries have quit coal, including Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg and Malta. Altogether, Europe emits almost 10 percent of the world’s CO2. That might make it seem like ending coal use there won’t make a huge difference, but if they can do it then surely others can, too. And this turn-around in what was until recently an essential energy source has happened within our lifetimes. It’s not too late.

Trends

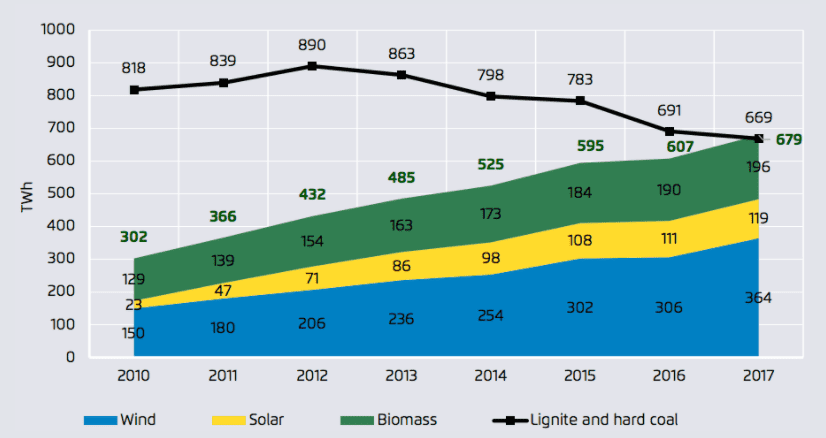

If this is a trend, it’s a good one. BloombergNEF is an organization that charts energy use. They note that in the last decade the cost of solar has dropped 87 percent and offshore wind by 62 percent.

They report that two-thirds of the world’s people live where these are now the cheapest sources of power. In 10 years, solar will be cheaper than fossil fuels everywhere. Many governments — surprising to me — continue to help fund the fossil fuel industry to the tune of $400 billion. Whether this is the result of the lobbying power of oil and gas companies is hard to say, but the writing’s on the wall when sustainable is cheaper.