Matt Homewood is bending his tall, lean frame over the edge of a black dumpster marked “landfill” in the rear parking lot of one of Copenhagen’s SuperBrugsen supermarkets. A customer service assistant had just heaved two enormous plastic bags into it.

Removing a jangling set of keys from his back pocket, Homewood slashes one of the bags open to reveal a trove of golden brioche buns, crusted rolls and a crispy plait of cinnamon pastry.

“These look like they’re from today,” says the food waste activist, picking an oat roll and biting a chunk out of it. “Yep. That’s been freshly baked this morning.”

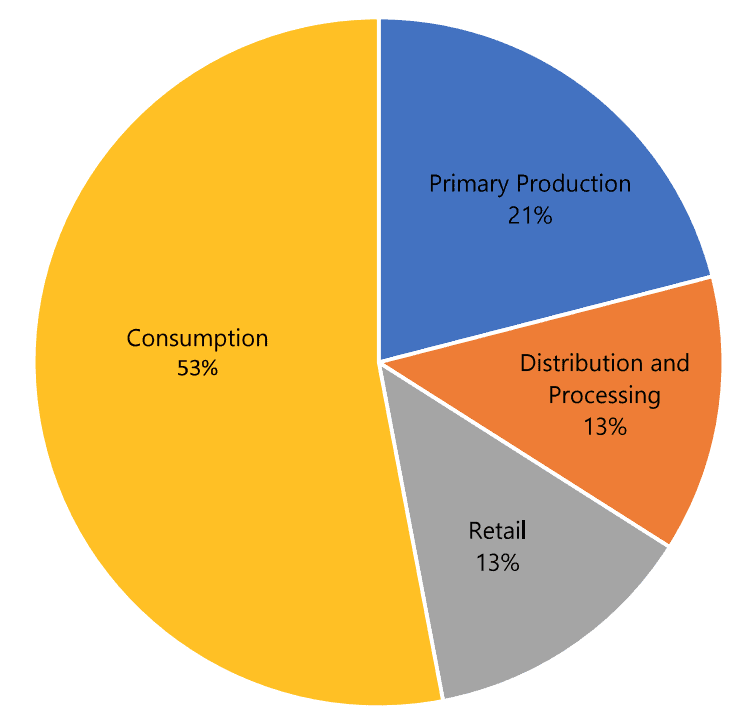

Homewood isn’t just seeking free pastry — he’s on a mission to save food from the country’s landfills and change Denmark’s food waste culture. A shocking 40 percent of the world’s food is wasted, contributing to approximately 10 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions. And Denmark, despite its aura of environmental infallibility, is one of the worst offenders, producing the most retail food waste per capita of any country in Europe.

The national government is aiming to halve the country’s total food waste in line with UN sustainable development goals by 2030. But it has yet to legislate mandatory reduction measures, like France, Spain and other European countries. And incentives and disincentives for wasting food are still insignificant to most supermarkets without enforcement.

That’s why a handful of private ventures are now attempting to address the problem of supermarket food waste. Their principal strategy? Find mouths to eat it.

Too Good To Go, a company launched in Copenhagen in 2016, was one of the first to jump on board.

Too Good To Go offers a digital platform on which food businesses can offer food approaching its expiration date in “magic bags” at a third of its original cost. Danish bakery chain Emmerys, for example, sells bags of baked goods worth 150DKK ($20.48) for 49DKK ($6.69).

Consumers can then use the app to find businesses selling the bags. Too Good To Go takes a 25 percent commission on each sale, with the rest going back to the original retailer.

“You don’t really know what food you’re going to get, but you know it’s all perfectly edible food that was otherwise going to waste,” says co-founder and director Jamie Crummie.

Crummie claims To Good To Go has saved more than 11 million “meals” in Denmark alone — equivalent to almost two bags per citizen. Nearly half of those have come from supermarkets, and the company has now expanded across 17 countries in Europe and North America.

In September last year, Homewood joined a similar company based in Norway called Throw No More. The founders wanted him to help them expand into Denmark.

Throw No More also tries to connect hungry mouths with soon-to-be-wasted food through a digital platform, but unlike To Good to Go, it allows users to choose the individual items they want to buy.

“When I found 160 packets of bacon in the dumpster, if that store had advertised those packs discounted to 60 or 70 percent, I think many people would have gone down to buy,” he says. “I could see the power of that solution.”

Instead of taking a cut of each sale, Throw No More charges the food retailers a flat rate of about 550 NOK per month. This encourages them to sell more by allowing them to choose their own rate of discount.

The battle to overcome food waste

The impact of initiatives like these is a subject of some debate. As efforts to divert would-be food waste have proliferated, critics have charged that some of the companies involved are simply greenwashing. Services that sell bruised or “ugly” produce, for instance, on the premise that it would otherwise be thrown away, have been accused of overstating how many of these items would actually end up in the trash. Homewood himself raises his concern that Too Good To Go’s model makes it possible for businesses to use the platform only when it suits their bottom line.

He believes it works well for bakeries and restaurants. But supermarket profit margins, he says, are too tight for Too Good To Go to make commercial sense when they’re reducing the cost of items by 66 percent, as well as paying a commission. This has led to some supermarkets using Too Good To Go as just another marketing channel, capping the number of magic bags available to buy on a specific day, Homewood claims.

But whatever the supermarkets’ motives, says Crummie, it’s impossible to deny that the platform is finding consumers for edible food that would have been tossed in the trash. Unintended marketing tool or not, Too Good To Go helps supermarkets recover costs, connects people with cheap food and reduces food waste, he says.

“Too Good To Go, as a model, is built not as a revenue driver or a profit maker,” says Crummie. “It’s there to recover sunk costs.”

Professor Jessica Aschemann-Witzel, director of Aarhus University’s MAPP Centre for Food Management in Denmark, believes pricing is the most effective mechanism for tackling food waste in the short term.

“People don’t like the feeling that, if they want to do something for sustainability, they have to give up on something,” she says. “People really respond to [price changes] because they perceive it as fair.”

But Aschemann-Witzel also believes the problem of food waste requires a diverse range of smaller initiatives to solve.

Some of these initiatives can come from the supermarkets themselves. Danish supermarket REMA 1000, for example, started labeling single bananas with stickers that read: “Take me. I’m single!” It also removed multi-buy offers that encouraged people to purchase more than they really needed.

An array of brands, including Carlsberg and Unilever, collaborated with Too Good To Go to introduce new food labels, too. Instead of the usual “best before,” they began labeling products to be sold in Denmark with “ofte god efter” (“often good after”).

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.But the real change will come when initiatives like these begin to cultivate a broad shift in public expectations. In many Western countries, the idea that anyone can walk into a store and purchase perfect peaches in December, or fresh baked bread at 10 p.m., has become so ingrained that it is viewed as an almost inalienable right.

To change perceptions like these, Aschemann-Witzel says, Danish supermarkets will need to start advertising “imperfect” products as equal to their perfect peers. “One thing that people criticize about these price reductions is that it means you’re manifesting that this product is less good than the other one,” she says. “Since then, the misshapen thing will always be perceived as less valuable.”

But persuading big supermarket chains to cooperate can prove challenging, as Homewood has discovered. Most countries are dominated by an oligopoly of companies (in Norway, there are four) that hold enormous power over the market. This makes it difficult for companies like Throw No More to succeed without providing significant incentives to the supermarkets. In Denmark, there are six big supermarket chains — if two decline to participate, that eliminates one third of Homewood’s potential customer base.

That’s why, alongside private initiatives, Homewood believes government regulation will play a crucial role in eliminating the waste.

“Without a food waste tax, technological uptake is incredibly slow because these businesses are so powerful,” he says. “They would just rather carry on with business as usual.”

He believes new legislation will be required to nudge capitalism in the right direction.

“When we deal with carbon emissions, for example, we’ve seen that the market is not going to solve that by itself,” Homewood says. “You need governments to intervene.”

Denmark’s general election next summer will delay any potential intervention for at least another year, according to Homewood. His recent petition requesting legislated annual supermarket food-waste reports received only 848 signatures. Within the next five years would be more realistic, he says.

In the meantime, private and non-governmental initiatives like Too Good To Go and Throw No More will do most of the grunt work. And that will still prove effective, says Aschemann-Witzel. “I think the biggest change can happen with those digitized solutions where the consumers can find discounted products.”