Pull a thread long enough and you can unravel an entire sweater. That’s the theory that drives Blue Tin Productions, a worker-owned clothing manufacturing collaborative in Chicago. Launched in 2019, Blue Tin’s goal goes beyond just employee ownership — it is working to dismantle the very exploitation that propels the bulk of the fashion business.

Even as fashion has worked hard to burnish its socially conscious bonafides, using more sustainable materials and aligning its marketing with social justice movements, the basic operating premise of the industry has remained the same: clothes are manufactured in far-away factories using cheap, unseen, exploitable labor. The problem is bigger than mere outsourcing. By keeping its global network of disempowered workers invisible, the industry has avoided tough conversations about its practices.

“Sustainability has become a more mainstream part of the conversation in the fashion industry,” says Hoda Katebi, the founder of Blue Tin. “But labor is still this terrifying monster people don’t want to discuss. Everyone still relies on colonialism to produce their goods.”

Katebi launched Blue Tin as a response to this reality. An Iranian-American activist and author who was acclaimed for her political fashion publication JooJoo Azad, Katebi’s vision from the beginning has been to take the very people who are normally exploited by the fashion industry – immigrant and refugee women — and put them at the helm of it instead.

“Everything relies on immigrant labor, primarily undocumented and exploited, who often come here based on American bullshit and economic imperialism,” she says. “The U.S. often needs a reality check when they talk about immigration and labor.”

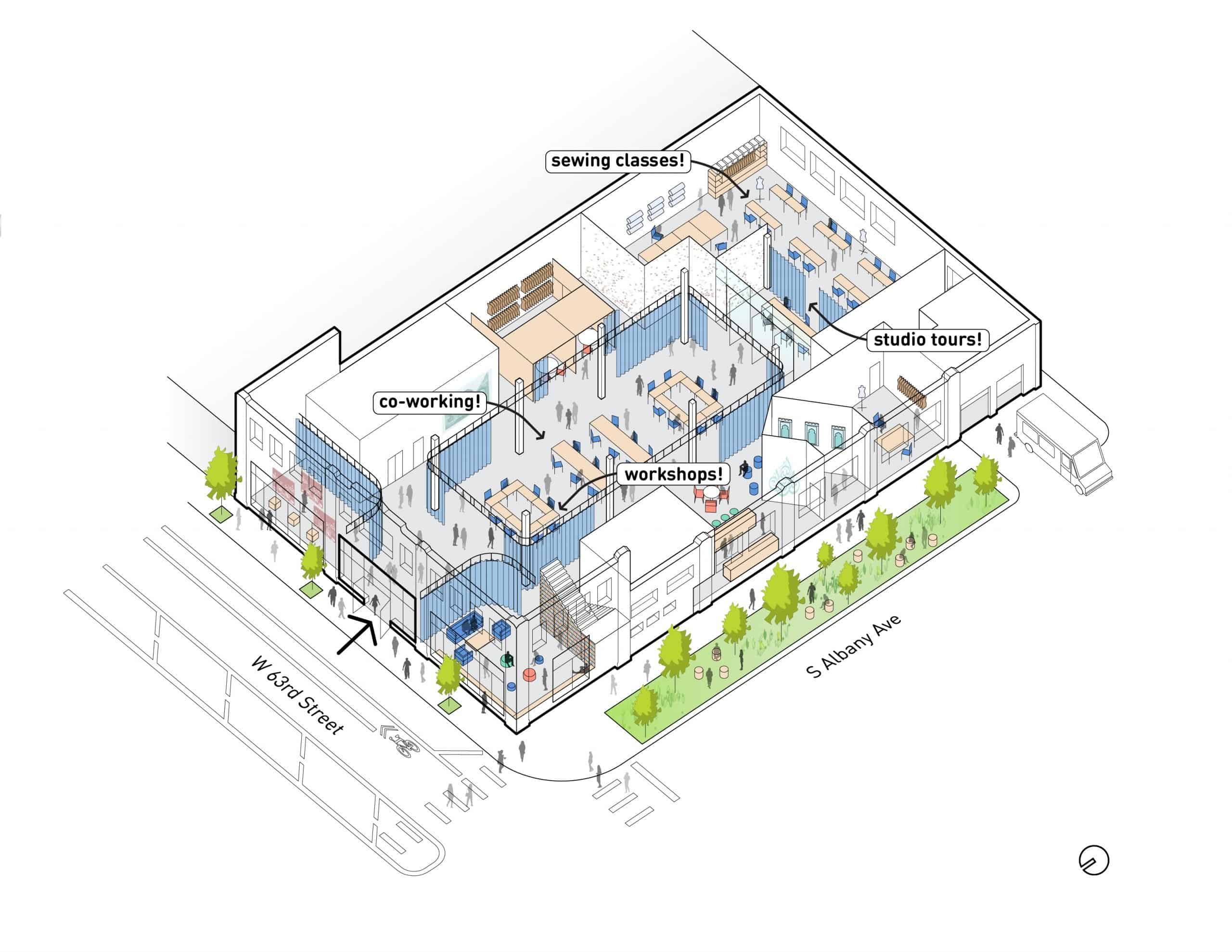

Now, the collective is launching a major expansion. This year and next, Blue Tin will crowdsource funding to build out a new $2 million home, 63rd House, an adaptive reuse of a 11,250-square-foot post office on the city’s working-class southwest side. The space will become both an economic anchor for the neighborhood and a model for truly sustainable manufacturing and labor practices. To Katebi, it is much more than a local concern.

“Ultimately our long-term goal is to have the new space be a model that can be replicated by garment workers globally at scale,” she says.

Revealing the invisible

Blue Tin, named after the Danish cookie tins where many home sewers store their needles and threads, does runs of up to 30,000 pieces, making everything from lingerie and underwear to hoodies and high fashion dresses. It operates out of a spare college classroom, and is focused on reducing waste and running the business via collective decision making.

When Katebi started to reach out to potential owner-members in 2018, tapping a network of local community groups, more than 100 women showed up to express interest. Initially supported by a series of fundraisers, the work has been gratifying and empowering for members — including a Syrian refugee and a Nigerian immigrant escaping an abusive relationship — who have found the co-op model engages the community and gives immigrant and refugee women, who typically lack economic opportunities and a road to management positions, control over their working lives.

View this post on Instagram

Katebi describes the operation as “a level of chaos that’s exciting and energizing,” with workers choosing the garments they want to work on — on some days you want brainless straight lines, she says, and on others, striking, fashionable dresses.

“Our approach to our work is very holistic,” says Katebi. “We try to think about how we can de-silo our work and the supply chain, and build the world we want to see.”

For Katebi, the new facility, powered in large part by rooftop solar panels, will explore and reflect many of the same values regarding power, community and equity that the collective does. But it will scale those values up to the level of a whole neighborhood. The current blueprint calls for half the headquarters to be dedicated to Blue Tin’s manufacturing. The other half will be set aside for the community. It will include a coworking space, a library, a gallery and room for local groups to meet and organize. It will also dramatically expand the size of the group, the kinds of collaborations they take on, their volume of work and their impact on the surrounding neighborhoods.

By literally letting the world in, 63rd House will be the antithesis of the typical black box sweatshop where the vast majority of the world’s clothing gets made. It will include a room to showcase the work of designers seeking to work with Blue Tin, and airy, accessible, light-filled manufacturing spaces. Jeanne Gang, an acclaimed Chicago architect and head of Studio Gang, which designed the space, envisioned the facility with two key ideas in mind: micro urbanism, focusing on the power of small interventions and community spaces to impact a nearby neighborhood; and the belief that a small manufacturing space, typically outside the concern of big architectural firms, was a proper vessel for community change.

“A small organization like this, which believes in good design, is someone we can help,” says Gang. “It’s a project worthy of attention. We’re using our platform to say, ‘What can architecture do?’”

A neighborhood focal point

Blue Tin picked the neighborhood known as Chicago Lawn because of its proximity to the city’s south and west sides. It’s a working-class part of the city where most of the collective’s members live. Katebi and others also have strong relationships with the neighborhood. The main drag, 63rd Street, contains partners such as Magnolia Screen Printing Studios, a collaborator, and the Inner-City Muslim Action Network, a community organization.

“What they’re doing is fashion,” said Hitoko Okada, a designer and curator who included Blue Tin in “Fashion Forward,” an exhibit about the apparel industry’s supply chain. “It’s switching the mindset from fashion being just about clothing to production, changing our minds and relationship to clothing and the way it’s been fed to us. It’s creating community and healing and an anti-capitalist model of fashion.”

Blue Tin also takes many larger fashion industry trends to another level, says Kim van der Weerd, a sustainable fashion advocate and former garment factory manager who co-hosts the Manufactured podcast. There’s increasing demand for reshoring, or what some are calling newshoring, bringing manufacturing back to the country of consumption and creating more visibility around labor rights and the supply chain.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.The collective also threads together social and environmental sustainability, and rebalances the industry’s financial risk in interesting ways. For instance, overseas, many manufacturing concerns need to provide all the materials, a huge capital outlay that can lead to sweatshop working conditions to cover overhead. Blue Tin, on the other hand, asks its production partners to include raw materials when soliciting work. This empowers Blue Tin to be more choosy and avoid the kind of deep financial risk that often leads to poor conditions and lower wages overseas.

“The big brands outsource the financial risk of hiring workers directly,” said van der Weerd. “I’ve had many conversations with people at big brands who didn’t know how their goods were made. They simply didn’t know how to manufacture clothes.”

Katebi sees the new home for Blue Tin coming together in two phases. The facade and exterior will ideally be finished by the end of the year so they can host events and fundraisers inside. In 2023, the full buildout will be complete and operations can commence in the new home. The jobs the site will create are important, but for Katebi, it’s about much more than that.

“We want to plant roots in a working class, disinvested, constantly overlooked neighborhood,” she says. “We want to build on our terms, for us.”