Waterline is an ongoing series of stories exploring the intersection of water, climate and food, told through the eyes of the people impacted by these issues. It is funded by a grant from the Walton Family Foundation.

A lone tractor trundles along a bumpy road in Banda, one of the most drought-prone districts in the North Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. Up until a few years ago, soil here would dry and crack into fissures deep enough for unwary cows to fall in. Today, as we drive toward a little village called Jakhni, we see rice paddies usually found only in much wetter climes. A large pond comes into view, and behind it, Jakhni.

Thanks to a revival of old farming practices and growing community involvement in all matters relating to water, this village is now known in India as a model jalgram, or water village.

Jakhni is a settlement of barely 1,600 people, mostly farmers. Its stony, hilly terrain is typical of Bundelkhand, an arid region spread across parts of the neighboring states of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. This region receives between 800 and 1,300 millimeters of rainfall annually, but locals quip that like their children, who all tend to migrate for better opportunities, the rainwater runs off too. The rocks that lie beneath the region are not very porous, and there are relatively few aquifers (layers of underground water). As a result, most of the rainwater flows away from the region instead of being locally absorbed.

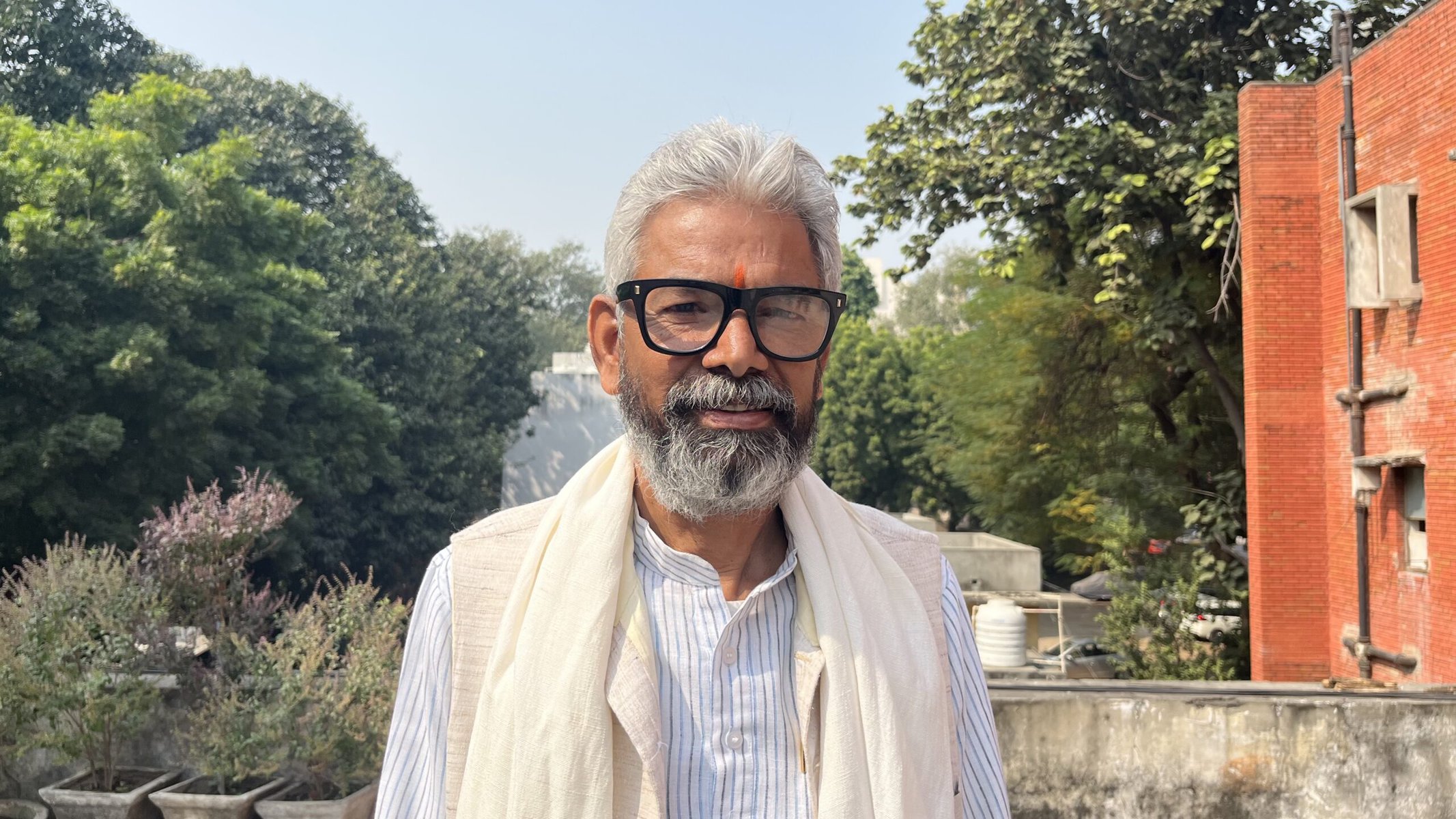

“Growing up, the water scarcity we experienced in Jakhni was scary,” Uma Shankar Pandey, a 52-year-old resident of Jakhni, recounts.

Farmers routinely saw their rain-fed crops fail. As the summer heat mounted, women, on whom the task of fetching household water fell, would walk long distances to find water sources. Pandey, a social activist, happened to attend a water conservation seminar in New Delhi in 2005, where he heard the late President APJ Abdul Kalam speak eloquently about rainwater harvesting and the impact the simple task of conserving rainwater could have.

“In his talk, Dr Kalam floated the idea of ‘jalgrams,’ or villages that practice water conservation and harvesting,” Pandey says, “and I thought — if there’s a village that needs to adopt such practices, it is Jakhni!”

Pandey did not have to look far for water conservation solutions. Traditionally, farmers in Bundelkhand trapped rainwater in their fields by building bunds, or raised embankments, around them. Pandey suspected that returning to this age-old practice of capturing rainwater where it fell could ease modern water woes. But he had to convince his fellow villagers first.

“People in my village are not rich, but they’re canny,” Pandey says. “Most responded to my suggestion saying they’d wait one season and see how our bunds performed.” Only 10 farmers agreed to do the extra labor of making bunds on 25 hectares of farmland. The practice worked, and the farmers had a good harvest of rice without having to depend upon the rain for irrigation.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.The following year, more farmers began making bunds, and they were able to cover over 300 hectares. But the bunds needed a lot of repair and maintenance as they kept getting eroded. That was when Pandey came up with the idea of planting trees, even an extra crop of lentils, on them to reduce erosion damage. The idea worked. He called this campaign Khet mein med, med par ped (bunds in fields, trees on bunds) and began thinking of other ways to ease the water shortage: desilting and deepening village ponds, building new ponds near fields, reviving dry wells and planting trees.

Together, and without any funding from the government, the residents built ridges and bunds in all their fields, planted trees and crops on them, and used the conserved rainwater for irrigation.

Over the next decade, the impact of this kind of conservation spread. In 2016 and 2017, the Indian government developed 1,050 ”water villages” across the country based on the Jakhni model.

But back in Banda district, there was still more work to be done. When Heera Lal took over as district magistrate in 2018, he saw right away the impacts of the water crisis. On his very first day, local residents blocked an arterial road to protest the lack of drinking water in their village. “I thought to myself, how can Banda’s residents be expected to survive, let alone thrive, without water?” says Lal, who is credited with improving Banda’s water availability today.

The officer had seen Jakhni’s success story first-hand, and as the top functionary of the district administration, he used all the funds at his disposal to spread its water conservation model of building bunds, desilting wells, constructing new ponds and more, all across Banda district. By the end of 2018, according to the district magistrate’s office, the Jakhni model had been implemented in 470 villages in the district.

Then Lal went a step further, exhorting Banda farmers to also build contour trenches to stop and contain water flowing downhill. And vitally, people began to meet regularly to discuss their water supply issues: “In 2019, along with WaterAid India, I organized jal chaupals [water budgeting meetings] in all these villages to convince locals that if they were extracting groundwater, they also needed to recharge it,” Lal explains.

The idea of water budgeting — evaluating the availability and sustainability of a water supply by tracking the movement of water into and out of it — is not new. In Banda, however, rather than experts, it is the local community who gathers in the village chaupal (central square).

In the summer of 2019, I attended a jal chaupal in Mahuee, a village not far from Jakhni. Using a water budget checklist developed by WaterAid, villagers charted all their existing water sources. Then, they estimated how much water they consumed in their daily activities, on a table that resembled a bank statement. Last, they estimated what, if anything, they had done to replenish their water sources.

A Mahuee local, Munni Devi, said that the exercise gave much food for thought. “We know that we can’t keep withdrawing money from our bank accounts without depositing and saving some,” she mused. “Then why have we never thought the same way about water and other natural resources?”

Lal remembers how such meetings not only sensitized people about judicious water use — they also spurred them to get involved in dozens of micro-projects to recharge water in their neighborhoods. These included digging soak pits around hand pumps and other community water sources (to channelize waste water back to the underground aquifer); harvesting rainwater from individual rooftops, desilting old ponds, digging contour trenches and more. In just one year, the campaign, called Bhujal Badhao Payjal Bachao (recharge groundwater, save drinking water) constructed 2,605 contour trenches, around 260 wells and 2,183 hand pumps, creating a water conservation capacity of 3,930 kilo liters. It was recognised by the Limca Book of Records in February 2020 for constructing the most contour trenches and holding the most jal choupals in a single month. The district administration of Banda also received the Smart Cities award for this achievement in 2019.

But most importantly, these efforts made a measurable difference in the water supply: according to Lal, by 2020, groundwater levels rose in Banda by nearly 1.4 meters.

Today, the village of Jakhni has 33 wells, 25 hand pumps and six ponds that remain full of water throughout the year, attesting to its recharged aquifers. Banda district has the highest number of wells in the state. In the first quarter of 2023 alone, almost 800 wells were dug, with 2,552 others in progress. During this same period, the district administration made 4,200 bunds, 200 new ponds and 4,500 soak pits.

Moreover, the practice of bund-making has been adopted by Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and other Indian states. Pandey attributes this to the easy replicability of the model. “The fact that bund-making needs only individual effort and minimal public funds — and yet is capable of having a profound impact on groundwater levels — has made it easy to convince civilians and governments to adopt it,” he says. For his efforts, Pandey was awarded the Padma Shri, India’s fourth-highest civilian honor, in 2023.

Yet these conservation practices represent a crucial step toward water security at a time when estimates suggest that by 2030, global freshwater demand could outstrip supply by as much as 40 percent, and approximately 1.6 billion people across the globe may not have access to clean drinking water.

Meanwhile, Pandey plans to start the country’s first water university within the coming year and says his work is far from done. “The university will synthesize insights about water conservation and water security from across India,” he says. “Rather than just academics and experts, I’d like to see ordinary people with practical experience teaching there.” His phone rings constantly, and his ringtone, the Hindi version of the anthem “We Shall Overcome,” seems oddly appropriate. “We have to keep at it, build bunds in other regions, and convince more people about the importance of every drop of rain,” he says. “For water can’t be made — it can only be conserved for the generations to come.”

Video footage of Bundelkhand’s 2016 drought appears courtesy of Uma Shankar Pandey.