Bellingham, Washington is a small bayside city about 20 miles south of the Canadian border with the oddly candid nickname “City of Subdued Excitement.” It’s a fitting motto, particularly in regards to the state’s new proposed housing policy, which could be filed under “obscure yet groundbreaking” — and could help to alleviate the housing crunch in Bellingham and other cities like it.

Washington’s new bill will “increase housing unit inventory by removing arbitrary limits on housing options.” In plain English, what that means is that groups of people who aren’t family will be allowed to live together. Washington is one of many states with old laws on the books prohibiting such living arrangements — a vestige of zoning regulations aimed at prioritizing the nuclear family and limiting the availability of affordable housing through boarding houses. In their zeal, however, such laws put an end to a useful urban housing model: affordable dwellings shared by strangers, a form that’s perfect for today’s housing-stressed cities.

In many ways, Bellingham is exactly the type of city that could benefit from more shared housing. It’s the home of Western Washington University, whose students often live together for social and economic reasons. The city also has a particularly robust LGBTQ presence, a community that has been creating intentional communities for decades. And issues with homelessness have pushed local officials to advocate for new housing solutions, like a tax increase to fund new housing, or using federal American Rescue Plan dollars to buy properties and convert them to shelters.

Bellingham is emblematic of a stark reality: The U.S. is facing a steep rise in housing costs and record low housing inventory. U.S. housing gained $2.5 trillion in value in 2020 — the highest shift since 2005 — and the median home price was up 19 percent in April 2021 compared to a year earlier. At the same time, multigenerational living is growing in popularity, with some 20 percent of Americans — 64 million people — living multi-generationally. In 2020, the average household size went up for the first time in more than 160 years.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Add all of this together, and throw in the fact that remote work is changing the geography of where Americans live, and you have an affordability crisis that is spreading across the country, especially to small cities like Bellingham. Helping people room together is once again becoming a tool for mitigating this crisis — a tool that’s more than a century old, but just as effective as ever.

An old idea for the modern era

Around the country, cities and states are seeking ways to house people more affordably by lessening regulation around the single-family home. Whether they are like Minneapolis, which allows zoning for anything up to a fourplex in all residential neighborhoods, or California, which has made it much easier to build backyard cottages, there is increasing recognition that more residential flexibility will bring more supply (and, in turn, more affordability) to neighborhoods. Allowing more unrelated people to live together, as states like Oregon and cities like Denver have done recently, is yet one more way to remove the barriers that keep people from accessing naturally affordable housing.

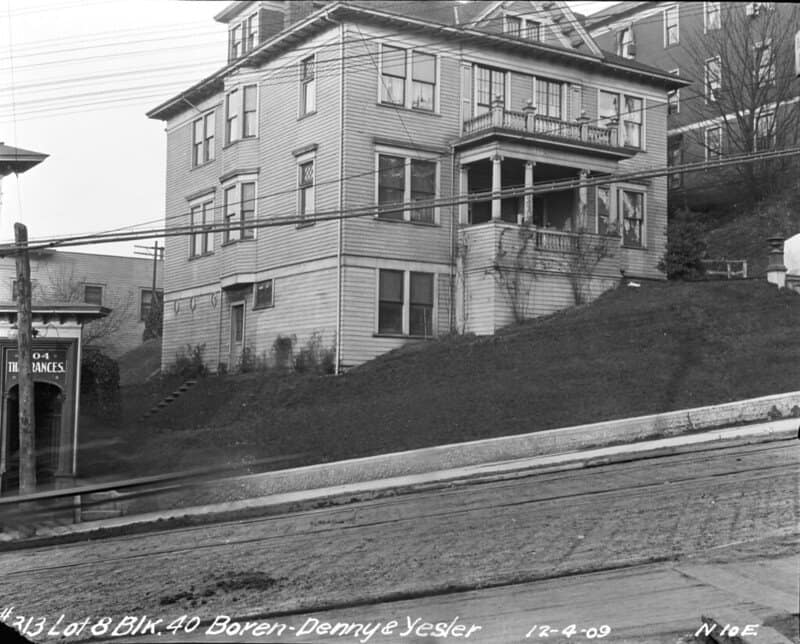

Boarding houses and SROs used to be very common in the United States. In the 1800s an estimated one-third to one-half of urban residents either hosted boarders or were boarders themselves. This style of housing accommodated a quadrupling of the American population over the 19th century, and enabled people to live affordably enough in walking distance of daily needs and amenities.

But throughout the second half of the 20th century, these housing types gradually disappeared as a result of zoning that prioritized single-family housing, and explicitly made these housing types illegal. While racist practices like redlining prevented people of color from buying homes in white neighborhoods, policies banning group living were likewise intended to keep white, single-family neighborhoods out of reach of certain groups: people of color, lower-income extended families, groups of friends, or single laborers. It didn’t help that the only SROs or boarding houses that continued to operate were often in disinvested urban areas.

Of course, people have always lived together outside typical family arrangements, acknowledges Michael Andersen, a senior researcher at the Seattle-based Sightline Institute. But rules limiting homes to three unrelated people were only selectively enforced, he says, and often at “points of cultural difference.”

“LGBTQ people have built their own ideas of family,” Andersen says. Meanwhile, immigrant families have a higher tendency to live multi-generationally or with other families. “This bill gets City Hall regulations out of people’s homes” and lets them live as they’d like, he says, referring to the Washington legislation. It also disarms those who want to use single-family zoning to control who, exactly, lives in a neighborhood.

The stigma associated with communal living is starting to be undone, in part due to co-living, which provides private bedrooms but shared spaces and amenities — reminiscent of SROs or boarding houses. But because most new co-living options are located in trendy neighborhoods of expensive cities, they have primarily won over an affluent, younger customer base that is additionally enticed by flexible pay-by-the-month leases and chicly furnished spaces. Advocates for co-living point to the housing form’s ability to foster intentional communities, add density to neighborhoods and provide housing to those without the job security that’s often required by landlords.

Andersen sees the potential for this new legislation to open up new models of housing people within the single-family home paradigm. “By legalizing group homes, it opens up the potential for new business models,” he says. Andersen himself lives in a co-housing development in Portland, which he says has provided him with abundant social experiences and a sense of security. He acknowledges this idyllic housing situation wouldn’t be possible without zoning that enables it — and developers who can specialize in building this housing type.

The U.S. has a whopping 54 million spare bedrooms. As cities and states liberalize their housing regulations to allow more people to live together safely and affordably, it is making a dent in the country’s housing crisis. Legislative changes like this one in Washington are ahead of their time — and a reason for some subdued excitement.

To learn more about the return of shared living, check out the author’s book, Brave New Home: Our Future in Smarter, Simpler, Happier Housing