It’s a cold winter morning in deepest rural Wales and Cassandra Lishman steels herself to face dawn’s frosty bite. She wakes up her 15-year-old son and 17-year-old daughter and leaves the insulated warmth of their cobwood roundhouse. She feeds the dogs, lets the chickens out of the coop and ambles up the hill to smash the ice in the sheep’s drinking trough. Her daughter feeds the horses, and her son lights a fire to kickstart the house’s solar thermal heating.

In the afternoon, she harvests leeks for dinner and cuts up a batch of pumpkins to put in the freezer — to make space she takes out some redcurrants and starts the week-long process of making jelly. In the summer, there’ll be hours more work to fit in: gardening, running willow-crafts workshops, building cobwood outhouses. “Then there’s the maintenance of all the fencing, which is constant,” she sighs. “This life isn’t for the faint-hearted.”

In Wales, the average citizen uses almost three times their share of the world’s resources. But Cassandra and her family are part of a groundbreaking scheme launched by the Welsh government in 2011 that aims to address that imbalance. The One Planet Development Policy (OPD) and its predecessor, Pembrokeshire’s Policy 52, allow people to bypass tight planning laws and move to protected areas to live ecologically sustainable lifestyles.

So far, 46 individual smallholdings have signed on to the programs, which require residents to sustain themselves using the resources available on land they inhabit. The policy aims to combat an array of problems: rising temperatures, soil degradation, rural depopulation, a rampant housing crisis and wasteful global supply chains. But at its most basic level, the OPD is an experiment to prove that, by limiting consumption and allocating resources wisely, ecologically responsible development is possible, even in pristine environments.

“A bold and creative policy”

“It was a bold and creative policy when it was introduced,” recalls Dr. Neil Harris, senior lecturer in statutory planning at Cardiff University. “You can’t build new homes in the open countryside — it’s a big no-no in the planning world. So it went against the grain. In Britain, there’s been a strongly protectionist approach to the countryside since World War II. It’s considered a place for recreation and food production, but not a place to live. It’s an attempt to protect nature from sprawl. Other European countries have similar containment policies.”

The OPD policy in Wales is one of the rare exceptions to this rule. It comes with stringent restrictions requiring applicants to prove they can live within a set of defined environmental limits. To qualify for the scheme, there are four requirements. First, each household must use only their global fair share of resources, which has been calculated by the Welsh government as equivalent to six acres of land. Second, applicants must show that within five years this land can fulfill 65 percent of their basic needs, including food, water, energy and waste. Third, they must come up with a zero-carbon house design using locally sourced and sustainable materials. Finally, they must set up a land-based enterprise to pay the sort of bills — internet, clothes, council tax — that can’t be met with a subsistence lifestyle.

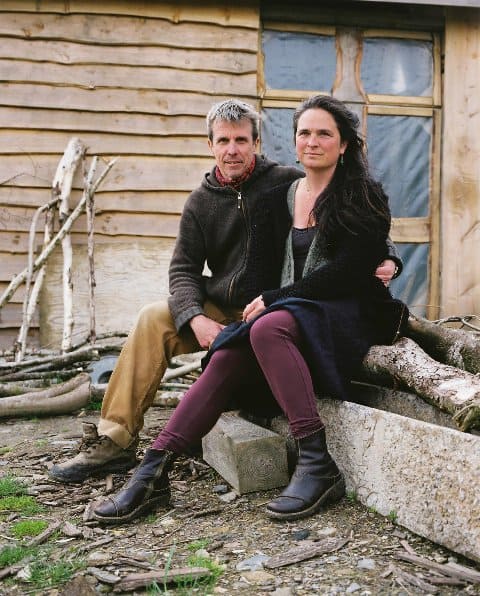

Cassandra’s smallholding, Plas Helyg, where she lives with her husband and two children, is nestled in bucolic Pembrokeshire in southwest Wales. It’s part of the Lammas eco-village, a 70-acre site that had previously been earning £3,000 (USD $4,100) a year from sheep grazing but now serves as home to nine OPD households. The Lammas received planning permission in 2009 under the county’s Policy 52 for low-impact living, which was subsequently scaled up into the national OPD policy.

Plas Helyg gets all its electricity from its own solar array and the village’s shared hydropower. The lion’s share of the household’s heating comes from burning its own wood; the hot water comes from solar. Around 30 percent of the family’s food comes from their land — they grow vegetables and fruit, and keep chickens for eggs and sheep for meat and wool. All their water comes from a local spring.

The household’s land-based enterprise involves growing willow, and the family harvests around 2,500 trees each year in order to make baskets and sculptures or sell cuttings and bundles. On the day we spoke, a customer was picking up an order of willow from Cassandra, so she bundled the branches her son had cut the previous day into ten kilogram parcels and dragged them down the drive for collection. She also had an Etsy order for a willow heart, so she soaked some twigs in gelid water and fashioned the malleable wood into shape before heading off to the nearest post office. For extra money, she holds willow-craft workshops for the local adult learning association.

From a regulatory perspective, someone applying for OPD planning permission needs to first prove their smallholding will come within the OPD limits within five years. From that point, the household must prove it is maintaining those standards by completing annual monitoring reports for the local council.

“In the annual report, we record how much food we’ve produced, how much willow we’ve sold, how many workshops I’ve done, etc.,” Cassandra explains. “We estimate how much firewood, water and electricity we’ve used for the year. We record all the animals’ costs as well, and our transport costs and biodiversity actions. And at the end of that we provide two figures, using general market prices, for how much we’ve produced and how much we’ve consumed.” According to Cassandra, for a family of four, those “basic needs” amount to around £10,000 (USD $13,700) a year; meaning an OPD household would need to produce equivalent to £6,500 (USD $8,900) either “of or from the land.”

Low-impact, low-cost development

Although its numbers remain small, the OPD policy is widely lauded as a success. It’s allowed a number of committed individuals to pivot to a more planet-friendly existence in a relatively affordable manner — Plas Helyg cost £30,000 (USD $41,100) all in. “There can be tension between affordable living and sustainability, but in the OPD we have an exemplar of low-impact, low-cost development. That’s exactly the kind of thing we want to support,” says Julie James, Minister for Housing and Local Government.

But the policy hasn’t been without its critics. In November, councilors in Carmarthenshire called for the OPD to be reviewed and potentially put on hold, citing resentment among locals who were finding it difficult to obtain planning permission to build homes on their land for their families. “Some of the early planning approvals for OPD smallholdings were at appeal, which suggests a degree of local political resistance to the policy,” says Harris.

“But generally these tensions have been solvable,” says James. And as the policy has gone on, there’s been an increasing acceptance of it. The OPD community has done a lot of outreach — led by its volunteer advocacy group, the One Planet Council — to demonstrate their low impact, and to show that their new produce and services could provide a boost to local economies. “That’s won most people over,” says Harris.

Cassandra remembers the initial distrust of the Preseli Hills residents when the Lammas first arrived. “It’s a very Welsh-speaking area and there was a feeling we would dilute the local culture and language… But that completely disappeared in a year or two. It really helped that our children went to the local school and learned Welsh.”

“There’s no going back”

Looking forward, the policy is “absolutely here to stay,” says James, and the current government is looking to apply some of the things it’s learned from the program to its wider housing plans. OPD has been part of the inspiration for the Innovative Housing Program, where the government provides grants and loans to de-risk novel sustainable-building methodologies so that people can invest and scale them up. The government then uses the most successful methods in its standard social-housing construction and retrofitting.

The government also recently changed Welsh development policy to stipulate that all new developments on public land must consist of 50 percent social housing and 50 percent from a mixture of tenures, including cooperative housing, community land trusts (CLTs) and shared equity schemes. “There’s nothing to stop us doing a One Planet development as part of a CLT or a cooperative model,” says James. (CLTs are community-run, nonprofit landholding organizations that help low-income buyers obtain homes.) “Those kinds of affordable housing finance models would make the OPD lifestyle available to a wider segment of the population. There’s a CLT in Solva, Pembrokshire that’s doing just that.”

Equally, the policy sets a perfect template for other small countries that have general constraints on development in their countryside, posits Harris. In England, the counties of Dartmoor and Cornwall are using the OPD framework to put in place similar initiatives, and countries such as Ireland and New Zealand are exploring the policy’s potential.

For Cassandra, the OPD life has been a tough but fulfilling experience. She remembers the hardship of moving, with a 14-year-old disabled son and two small children, to an empty field with nothing to their name — no electricity, no shelter but an old truck and a small yurt, and having to collect water with a wheelbarrow from a local tap. But would she do any of it differently? Not a chance.

“Once you’ve lived like this, there’s no going back. I love living close to the elements, I love living with the sun and the water as my electricity, I love growing my own food and trees, and being in touch with the earth. It’s such a nourishing and joyful existence.”