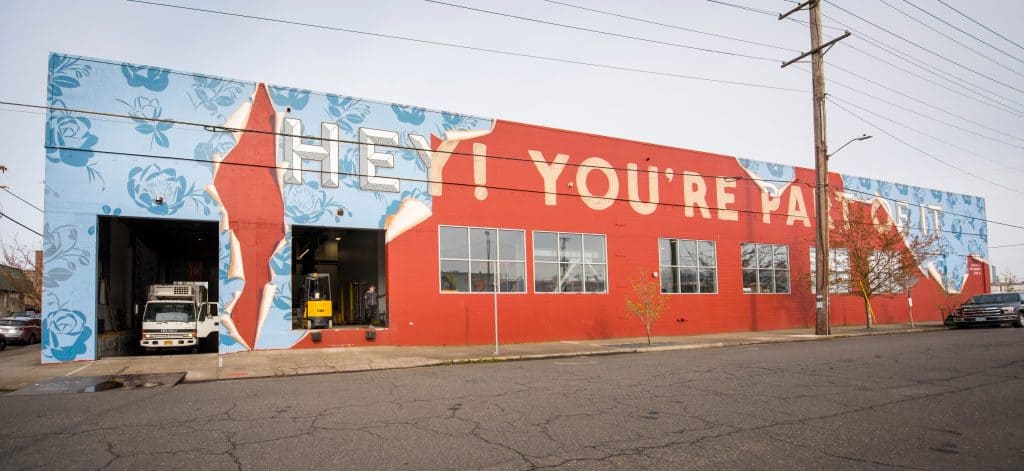

It’s Friday afternoon, and people on bikes and in cars are pulling up to an enormous red-brick warehouse in Portland’s Central Eastside to pick up their “Greater Good” boxes. Packed with local food, the $50 boxes are organized by local grocery chain New Seasons and wholesaler Organically Grown Co. A similar pick-up parade occurs on Wednesdays, when people cart away “Dock Boxes” of fish, shrimp and crab from popular Oregon Coast seafood restaurant Local Ocean. And on Monday evenings, Farm Punk, a farm in nearby Gresham, drops off its 50 community-supported agriculture (CSA) shares here, to be delivered the next day to eaters’ front porches via electric-assist trikes.

This is the “new normal” at the Redd on Salmon, an enterprise that’s optimizing Portland’s local food system and helping farmers, ranchers and fisherfolk adapt to a post-Covid reality. Even in the before times, the Redd on Salmon served as a solution to the infrastructure dilemma for small and mid-size farmers, who face all kinds of logistical challenges as they try to get food to consumers. Without the production volume to justify large-scale storage and transport systems, small farmers often spend a full day on the road each week, burning precious time and money driving to restaurants and supermarkets, dropping off their wares one at a time. They also need to market and often sell their own goods — skills many farmers don’t know the first thing about.

The Redd solves all these problems in one fell swoop, acting as a distribution hub, an affordable storage space and a shared industrial kitchen. Ecotrust, the environmental think tank behind the Redd, also hosts a business accelerator, helping small farmers to scale up. Currently, the Redd supports more than 150 small to mid-size food-related businesses. From 2018 to 2019, the facility’s core tenants saw a 45 percent increase in job creation and a 12 percent increase in jobs at or above the living wage.

Medium-sizing small farms

The Covid-19 pandemic has exposed the failures of the industrial food system. Grocery stores have run short of pasta, canned beans, flour, yeast and meat. Farmers, unable to sell to school cafeterias and chain restaurants, are dumping their milk and plowing under their onions. When 20 gargantuan meat processing plants were shuttered by coronavirus outbreaks, farmers were left with no choice but to euthanize hundreds of thousands of pigs and millions of chickens.

As Michael Pollan noted in his recent piece in the New York Review of Books, our industrial food chain is broken, but local food systems, like the one championed and supported by the Redd on Salmon, are proving to be more resilient. “The advantages of local food systems have never been more obvious, and their rapid growth during the past two decades has at least partly insulated many communities from the shocks to the broader food economy,” Pollan writes.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.The Redd on Salmon is an integral part of this system. It is what is known as a food hub, a centrally located space that facilitates the aggregation, storage, processing, distribution and/or marketing of regionally produced food products. Not only does the block-long space provide farmers a 2,000-square-foot cold storage facility (half freezer, half refrigeration), it has offices and “dry storage” space so local companies like Ground Up PDX (nut butters) and Hoss Sauce (hot sauce) can stash boxes and product at a central location closer to their customers.

The Redd solves the transport conundrum, too, with its main tenant, B-Line. A short-haul service with a fleet of electric-assist trikes, B-Line executes “last-mile” delivery without spewing carbon dioxide or jamming up the roads at delivery sites. Trike drivers load up their insulated trailers with up to 600 pounds of product and drop off food at restaurants, grocery stores and corporate cafeterias like AirBnB and Google. (B-Line also has one truck for deliveries that are further than three miles away. Founder and CEO Franklin Jones is saving up for an electric one.)

By providing an all-in-one distribution hub to farmers who could never afford one on their own, the Redd was conceived as a way to support what food systems experts call “the agriculture of the middle.” Ag of the middle producers are larger than those who sell via local farmers’ markets or CSAs, but smaller than those supplying globalized commodity markets. With logistical and marketing support from the Redd, these producers can scale up and eventually serve institutional outlets like schools, hospitals, grocery stores and corporate offices.

And lest you think this is a quirky boutique solution unique to Portlandia, know that there are over 350 food hubs around the country—from Durham, North Carolina to Traverse City, Michigan. A traditional food hub offers aggregation, marketing and often distribution for agricultural products. It might also serve as an incubator for micro-businesses. But the Redd takes it a step further, offering shared kitchens, a co-working space and even (across the street in the Redd East) an 8,000-square-foot event space with a state-of-the-art kitchen. Jim Barham, an agricultural economist at the USDA, calls the Redd a food hub on steroids.

Founded by Ecotrust, which has long been a champion of ag of the middle producers, the Redd runs a two-year Ag of the Middle Accelerator Program that helps smaller-scale farmers, ranchers and fisherfolk learn the basics of marketing, accounting, taxation and business structure — as well as helping them apply for USDA value-added producer grants. As part of their orientation, participants in the accelerator tour the Redd’s facilities; graduates often end up using the space in some way. Over 70 producers have either graduated from the accelerator program or are in it right now. The current cohort of 17 businesses increased their sales by $1.5 million, collectively, after one year in the program.

Keeping it local

Pre-pandemic, 30 to 40 percent of B-Line’s deliveries were to restaurants, corporate cafeterias or downtown businesses like Office Depot. Now that most of those are closed, the company has had to pivot, doing more frequent deliveries to New Seasons’ 18 area grocery stores, as well as serving as a physical hub for new direct-to-consumer services like the DockBox and Greater Good boxes.

“When the pandemic hit, there was a flurry of ‘panic buying,’” says B-Line founder and CEO Franklin Jones. As it did at many supermarket chains, demand skyrocketed at New Seasons, causing a backlog with mainline distributors like KeHE, UNFI and Supervalu. As a result, says director of brand development at New Seasons Chris Tjersland, these distributors limited the amount of product that could be shipped to each store, leaving them with empty shelves.

But because B-Line has pre-existing relationships with local farmers and producers, Jones was able to funnel products straight from these vendors through the Redd and into the aisles at New Seasons. Working with B-Line also allowed Tjersland and Jones to work directly with the producers of New Seasons’s private label line at a moment when traditional distribution channels were breaking down. While industrial farms were dumping perfectly good fruit and milk, B-Line was storing and delivering thousands of cases of Shepherd’s Grain flour, 800 cases of Rallenti Pasta and over 400 cases of Scenic Fruit frozen berries. Tjersland even worked with local companies Brew Dr Kombucha and Straightaway Cocktails to make New Seasons hand sanitizer, which was stored at the Redd and delivered via B-Line.

The pandemic prompted other positive developments at the Redd. Redd Campus Manager Emma Sharer was tasked with how to optimize the Redd East event space, normally booked with weddings, natural wine fairs and food-focused conferences. In late March, she was doing an ab workout on the waterfront when she ran into Jacobsen Valentine, founder of Feed the Mass, an affordable cooking school that teaches people how to make healthy meals from scratch.

The two struck up a conversation. “He was like, ‘My nonprofit is really struggling and I have this idea: how can we make meals for people who are missing access to them? Who are forced to buy fast food or packaged food?”

They cooked up a collaborative plan. Ecotrust would donate its Redd East kitchen to Valentine two days a week, and he would cook meals for unhoused and food insecure folks around town.

The FED Project was born. For the past month, Valentine and a handful of volunteers have been cooking two meals a week at the Redd’s kitchen; each meal can feed 200 people. The meals are packed up individually and delivered to folks around town who need them.

Ecotrust gave Valentine a small food budget and stipend. Plus, Sharer scored a huge food donation from Airbnb when the company’s Portland offices, including its cafeteria, closed in March. Since the company had been sourcing via the Redd, much of the food was high-quality and local. “There was cheese, sour cream, Camas Country flour, a lot of spices, chicken from Marion Acres, pork products from Campfire Farm, confit garlic, frozen berries,” says Airbnb’s food program manager Abby Fammartino, who estimates that the donation was worth $10,000 in total. Jacobsen and his crew made mac and cheese the first week and channa masala the next.

Sharer and Valentine hope that this particular project will live on even after the pandemic is over. “If we were to get more funding, could some of that go towards paying BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) farmers to purchase more product, supportive of the sourcing side of farming?” asks Sharer. “That’s our next step.”

One thing is clear: the Redd campus — and its robust local food community — helped keep flour and hand sanitizer on New Seasons shelves while mainline distributors couldn’t keep up with the spike in demand.

“What it [the pandemic] made me realize is that the supply chain infrastructure is broken,” Tjersland from New Seasons says. Jones, who hasn’t had to lay off anyone at B-Line as a result of his increased business with New Seasons, agrees. “The whole pandemic really shone a spotlight on how resilient the local supply chain could be.”