Along with Vienna, Singapore is often mentioned as a place that has “solved” the affordable housing problem that plagues many cities around the world. 80 percent of Singaporeans live as owner-occupiers in housing built by the government. 80 percent! And 90 percent of Singaporeans own their own homes. (More on what “homeownership” means in the Singaporean context in a moment.) Not only that, there is little segregation between the three principal ethnicities that live in the island city-state. And, given the availability of low-cost housing, there is less homelessness in Singapore than in many comparable cities …something that actually saves the city a lot of money.

Compare that to what’s happening in the U.S.

The developed world’s wealthiest cities are facing housing crises so acute that not only low-income workers, but also the middle and creative classes, find them increasingly difficult places to afford. Redfin, the real estate website, recently found that there was not a single home on the market in San Francisco that would be affordable on a teacher’s salary.

A city no one except the wealthy can afford is not really a city — which by nature thrives as fresh blood comes in — it is a gated enclave. The housing crunch in San Francisco, London, New York, Vancouver and lots of other cities where even moderately priced houses are scarce, however, is not inevitable. It’s often the result of policies and politics. The good news is that policies and politics can change. If we look beyond and examine what others have done we may find inspiration for what that change could be.

The Singaporean way

A lot of Singapore’s housing looks like what it is: efficient, affordable and government-built. In other words, not a lot of flair:

Now, admittedly, from my biased point of view, these endless towers scream dystopia — here are the human termite mounds similar to those proposed by Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright and other architects who were often said to hate cities. “Ugh, how can they live like that?” I ask myself. But Singaporeans don’t necessarily share my prejudiced opinion. For them, this housing is working. I realized I should listen to how they feel about their city and leave my snobby preconceptions behind.

For the residents, having an apartment in one of these towers is to have a stake in the place where you live, a place that is clean and well run and often includes amenities like parks, garden plots, food courts and nearby transportation. Here’s a rooftop community garden:

How did they do this?

It didn’t happen overnight. The British ruled Singapore for a long time, and they failed to provide public housing despite the city’s struggle with slums, squatters and homelessness. So, in 1960, just after the island became self-governed, its first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, initiated a five-year-plan through the newly created Housing and Development Board (HDB). Tasked with solving the city’s housing crisis, the HDB built over 50,000 homes in five years. By 1965, 400,000 Singaporeans were living in HDB housing.

Today, the city has over a million HDB units, and few Singaporeans live in apartments bought on the private market. What makes the Singapore model different from most other cities is that the vast majority of the city’s housing is owned by the government. This not only allows the city to virtually guarantee affordable housing for its residents, it fundamentally changes the nature of housing — in effect, it says that a home a place to live, not an investment to enrich an individual.

But that doesn’t mean Singapore is an island of renters. In 1964 a law was passed allowing folks in public housing to “buy” their homes. What they actually own, however, is a 99-year lease on the property. The government is still the actual owner, which means that while residents can buy, sell and even inherit property, the price is controlled. This hybrid system also means that the government maintains, renovates and upgrades the apartments free of charge.

Homeowners in other countries might find this setup odd. We’ve become accustomed to thinking of a home as an asset — often our most valuable one — and a way to reliably grow one’s wealth. Not being able to do this might seem too restrictive. But as we’ll see, Singaporeans view housing in an entirely different way: as a right for all, as opposed to a source of profit for some.

Many analysts hanker for a Singaporean solution to Hong Kong’s problems. The city-state realised early on that widespread home-ownership was essential to social peace. Over 80% of the population lives in homes built by government agencies, sold at subsidised prices. Phang Sock-Yong of the Singapore Management University says that, as far as housing is concerned, Singapore approximates the “ideal society” envisioned by Thomas Piketty in his book, “Capital in the 21st Century.” The bottom half of households own a quarter of Singapore’s housing wealth.

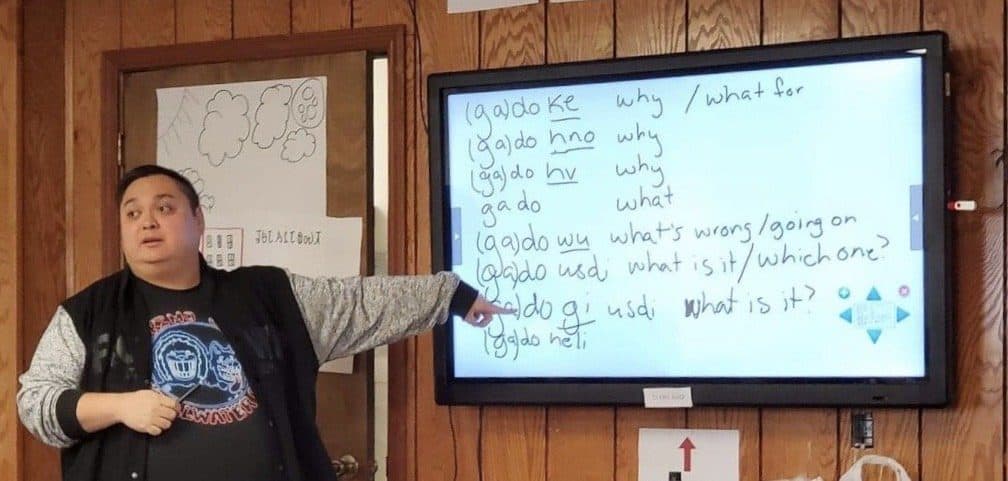

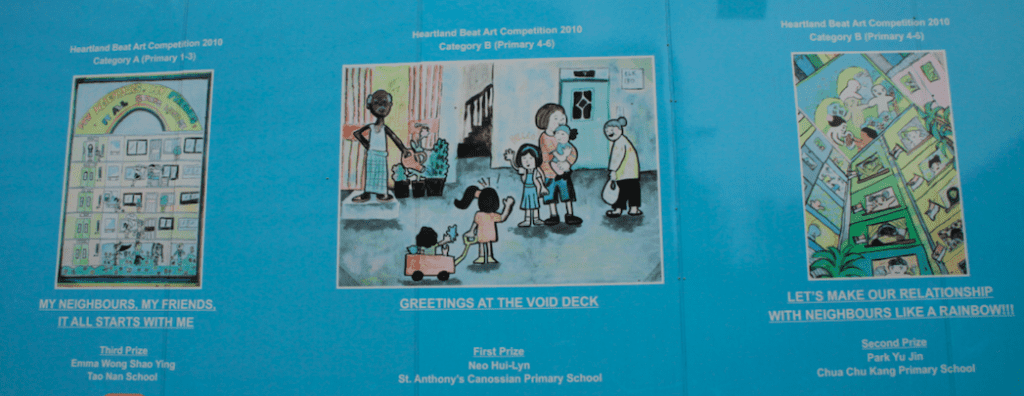

Diversity in housing

In parallel with creating a system that eliminates a range of housing problems, the city also decided that integrating the population was essential to the functioning of the city-state.

Singapore has citizens whose backgrounds are Indian, Malaysian and Chinese. With independence, it was determined to continue to be a multicultural and multiracial society, and to make it work. Laws were enacted to ensure that the highest political positions reflect the racial diversity of the city-state. English was chosen as the language used in schools so as not to privilege any one ethnic group. At the same time, a short military service became mandatory for every young male, forcing men from different cultures to work together.

Race riots in 1964 between Chinese and Malaysians left dozens dead and hundreds injured, and in 1989, quotas determining what percentage of each ethnic group can live in a tower were implemented. The goal was to prevent the creation of new enclaves and ensure diversity. Some enclaves still exist. In Little India, for example, I once witnessed the painless piercing that is part of the Hindu Thaipusam festival. (Devotees in trance have their skin pierced by long needles. Not for the squeamish.)

My biased viewpoint, again: People like me might bemoan the end of places like Chinatown, Calle Ocho and Little Italy. But Singapore has decided that these segregated enclaves are, in the long run, harmful to the overall unity and health of the city-state. While many in the West might find these restrictions antithetical to individual freedom, a city without strife can be viewed as providing another kind of freedom. It seems the folks in Singapore are willing to trade some freedoms for the quality of life they get in return.

From the top down

The policies described above are very top-down, implemented by a central authority that exerts extraordinary control over how people live. Folks from other parts of the world and other cultures may bristle at some of the ripple effects. There are laws outlawing chewing gum, feeding pigeons ($500) and connecting to someone else’s wifi ($6,400 or 3 months jail time). These may seem wildly exotic to those who don’t live there, but Singaporeans have largely embraced this top-down dynamic.

The city’s housing model helps illustrate why. Singaporeans see housing as a right and diversity in housing as a given. They may even pity those who don’t enjoy the same security and privilege. Top-down policies and practices established long ago have led to enviable social norms. The citizens have come to expect these things. The norms became the building blocks.

What both Vienna and Singapore have in common is that making housing available and affordable is considered a government priority and the responsibility of the state. It has worked. These are not communist or anti-business cities. (Singapore? Anti-business?) They are hybrids that mix state assistance and regulation with private investment. The state helps manage rapacious market forces for the benefit of its citizens.

But would you live there?

Singapore is the world’s third-richest country and has among the most millionaires per capita. A Gallup survey found that Americans are twice as likely as Singaporeans to not be able to afford food. Food! A 2015 Bloomberg survey found Singapore to be the world’s healthiest nation (the U.S. ranked 33rd) and infant mortality is about one-third what it is in the U.S. In education? Singapore is second in math, science and reading — the U.S. is 36th, 28th and 24th, respectively.

Confidence in government? Check. Entrepreneurial opportunity? Check. Lack of corruption? Check. I could go on and on.

And yet, when I mention all these positive qualities, a friend of mine inevitably asks, “But would you live there?” I think this question speaks to the tension between surrender and control every city must navigate. Singapore is a control-oriented place. There are lots of restrictions on religious rights, rights of assembly, homosexuality, the press, expression and opposition to the government. All of these are things folks in the West deem pretty essential. In the West, the rights of the individual are often prioritized, often to the detriment of the broader public. We in the West give up some quality of life and economic security, but dammit we can chew gum and even spit it out!

I do ask myself: What if? Would I accept some restrictions in exchange for a healthier, safer life among citizens who are less desperate, better educated and less crazy-angry? If not, why the hell not? Need we be absolutist? Is there a reasonable tradeoff?

This acceptance of restriction and control may be key to Singapore’s success. It’s sometimes referred to as the difference between “freedom from” versus “freedom to.” Freedom from fear, from want, from religious persecution, from discrimination, from financial insecurity (though to be sure, Singapore, too, has an underclass that struggles to survive)… I would offer that Singapoeans prioritize these while many Americans prioritize “freedoms to” — to say what you want, to criticize the government, to organize, to bear arms, to marry and have sex with others as long as no harm is done.

A couple of weeks ago, I asked whether we can borrow from the best aspects of what China does without endorsing the worst. In the case of Singapore, we face a similar question. Can we learn from Singapore’s successes with subsidized housing, home ownership, and cultural and racial representation, while simultaneously not feeling obliged to adopt every part of their restrictions and control? Or are they two sides of the same coin? Do those restrictions keep the good stuff running smoothly? Do Singaporeans happily accept that “freedom from” should be prioritized over “freedom to?” Should we? Would you live there?