A Patient Is a Person is a series about how whole-person health is transforming the patient journey. It is supported by funding from UPIC Health.

When Krystal Martin started surveying her neighbors in the southwest Mississippi town of Gloster about the impact of a local wood pellet manufacturing facility, she was focused on air quality. The facility has been fined multiple times for exceeding emissions limits, and Martin was worried about her neighbors’ health. From respiratory issues to eye and skin irritation, just about everyone in the town of almost 900 people felt some impact.

But air quality wasn’t the only concern. “You hear some people talk about the dust,” Martin says. “Some people said they were impacted by a lot of sound.”

Noise is just a part of life there, she says. Loud 18-wheeler trucks drive along the country roads every couple minutes. Machinery and loudspeakers echo out from the plant across the two-mile-wide town. But it wasn’t until Martin’s organization, the Greater Greener Gloster Project, partnered with Brown University epidemiological researcher Erica Walker that Martin began to understand the constant cacophony not just as an annoyance, but as another factor contributing to residents’ health.

“We knew it was a problem. People talked about it being a problem,” says Martin. “But we didn’t know it was noise pollution.”

Walker leads the Community Noise Lab, a research initiative that explores the intersections between noise and health. The connection between loud sounds and health extends far beyond hearing loss. Research is finding noise exposure has implications for cardiovascular and cognitive health. Yet, unlike other environmental stressors, noise has not been a major factor in community planning.

Research efforts like Walker’s are deepening our understanding of how noise permeates lives, arming communities with information to better plan for their health and their future.

“I want to empower citizens to be able to negotiate what comes into their communities, and negotiate thinking about noise as one of those things,” Walker says.

Sound plays a central role in how humans interact with the world, explains Walker. From a young age, kids learn about the importance of hearing as one of the five senses.

“We’ve legislated, regulated, discussed all of these other senses, but noise is the one that we kind of left out,” says Walker.

Now, research is showing just how grave exposure to noise can be. Noise can trigger a stress response, the same system that signals when our bodies are in danger. It has been linked to issues like hypertension, heightened risk of heart disease and impaired cognitive functioning. It can cause sleep issues and contribute to mental health conditions like anxiety and depression.

There’s a history, Walker notes, of “putting loud things” like highways, airports and industrial facilities “in communities that don’t have the power to fight back.” People of color and lower-income communities tend to be at highest risk.

While the health consequences of noise are becoming clearer, understanding of just how much noise is in people’s lives and communities remains hazy.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.In the European Union, a leader in recognizing noise as a health threat, member countries have mapped sound from roadways, rail traffic, airports and industry. Awareness in the US is lagging, according to University of Michigan professor of environmental health sciences Rick Neitzel. The US has two main national resources — one from the federal Department of Transportation tracking transportation noise, the other from the National Park Service. However, there aren’t good resources tracking noise exposure in other aspects of daily life.

But Neitzel sees awareness growing.

“I think people are starting to wake up and realize this isn’t just a nuisance,” says Neitzel. “It’s not just a necessary byproduct of modern life. It’s actually bad for us.”

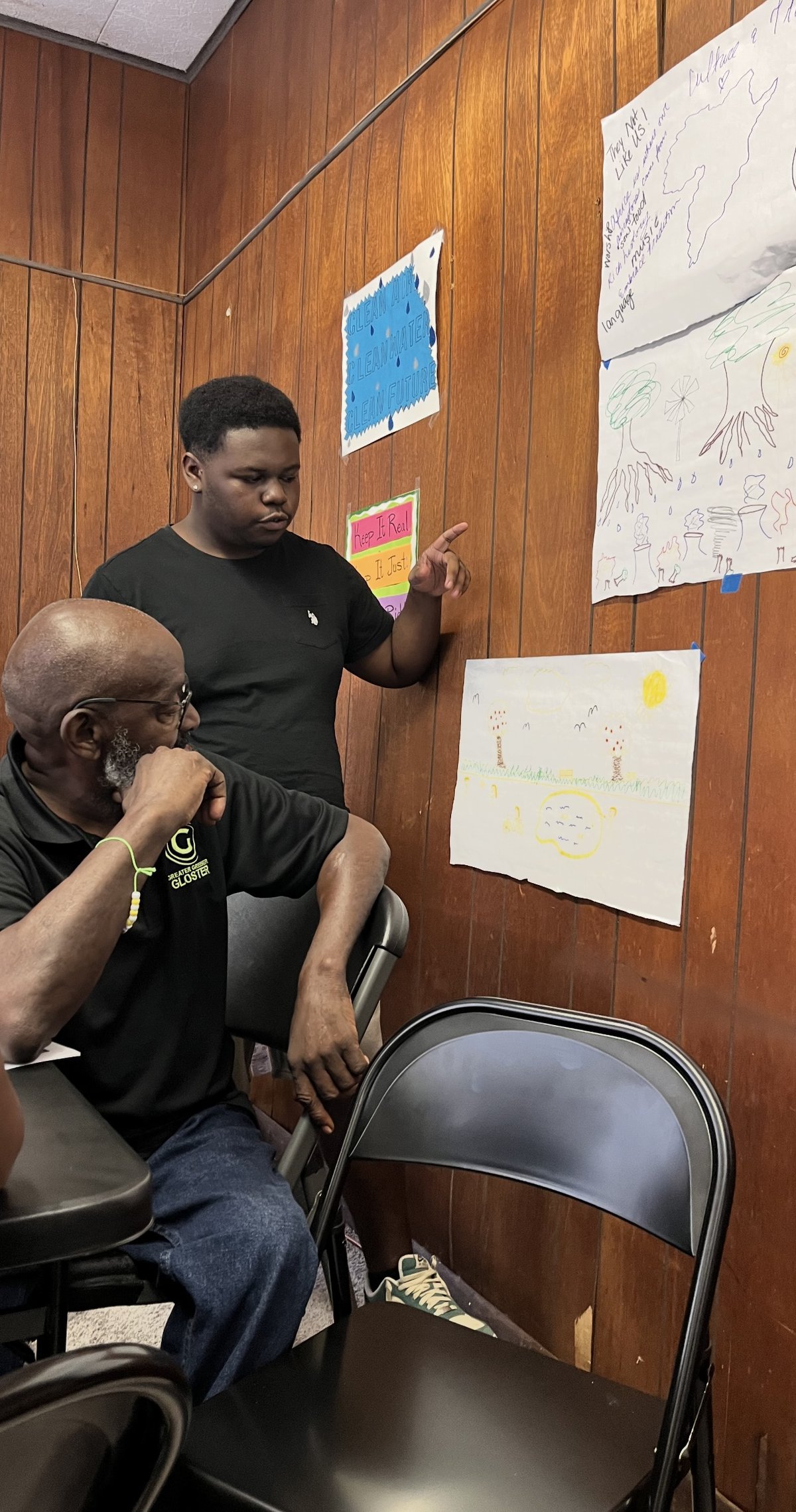

In Gloster, high school and community college students regularly reposition air quality and noise monitors around town.

They’re helping collect data as part of Walker’s ongoing research on the health effects of wood pellet manufacturing. The industry exploded in the US South to accommodate EU demand for fossil fuel alternatives, and has particularly impacted majority-Black, low-income communities.

Walker approaches noise as interconnected with other environmental factors, like air and water quality. Instead of prioritizing noise over the concerns of locals, Walker monitors a range of factors, including sound. Ultimately, research leaves residents with a package of data that can inform their planning and negotiations.

That set of data can spur change, as Walker saw in Boston. Neighbors of Fenway Park, home of the Red Sox, were rattled by concerts the stadium hosted in the off-season. When Walker collected data around the neighborhood, she not only found very high decibels of noise during concerts, but also low-frequency reverberations that particularly impacted closest neighbors.

Initially, interactions with Fenway Park were contentious, she recalls. But, over time, the venue became more receptive to the community’s concerns. The park invested in its own noise monitoring equipment, she says, and has continued to use her metrics to collect data.

“They see the importance of that, and the community really appreciates being heard,” Walker says.

In Gloster, Mississippi, Walker’s study found that noise levels were up to 10 decibels higher, or twice as loud, as a similar community without a biomass plant. Simply having this data available gives residents more power to negotiate terms of operations with industries, she explains: “A lot of the noise issues we have in our country have been uninformed planning, uninformed responses to things.”

“You can take everything that I’ve done with this and say, ‘No, we still want the plant,’” Walker says. “I’m happy because that’s an informed response.”

While awareness of the connections between health and noise is rising, there’s no one, straightforward path to address the problem.

Responses to noise tend to be enacted at the local or municipal level, explains Neitzel. Paris has sought to crack down on traffic noise with radars that pinpoint excessively loud vehicles, issuing fines to offenders. Though Neitzel isn’t aware of research on the technology, he says intuitively it makes sense that reducing loud cars will help.

Several European cities have lowered speed limits, leading to reduced traffic noise. When Zurich reduced speed on some streets from 50 kilometers per hour to 30 kilometers per hour (about 30 to 19 miles per hour), noise levels dropped, and residents self-reported less annoyance and sleep disturbance.

One change under way, Neitzel says, is the expanding fleet of electric vehicles, which he says are quieter than combustion engines in slow, urban environments. Another approach to highway noise is roadside barriers, which can reduce noise by up to 10 decibels.

Ultimately, Neitzel sees systemic approaches to planning as most likely to make a lasting impact, like expanding public transit and reducing vehicles on the road. He points to congestion pricing, an approach to curbing traffic and air pollution in cities by charging drivers at busy times of day. Cities that have enacted it also see traffic noise levels drop.

“It’s not like the city is going to get quieter overnight,” Neitzel says, “but I think those things have a much bigger chance of making a bigger impact over the long haul.”

For Walker, community involvement is the key to improving noise pollution. Addressing noise in a way that is equitable is a challenge. Within communities, noise complaints are sometimes wielded to target aspects of a neighborhood seen as “undesirable.”

“Noise can be a power thing,” she says. “It could be used to silence people, silence practices, silence the acoustical culture of a community.”

In Gloster, the din of the wood pellet facility can still be heard around the clock. “It’s mentally draining,” says Martin. “It’s mentally stressful.”

But now, Martin says, the community recognizes noise as a health factor along with the other air and water quality concerns. Armed with data showing the extent of the problem, she believes Gloster residents are well-positioned to push to curb the cacophony.

“The people in the community, we should not hear that 24 hours, seven days a week,” says Martin. “Maybe we can now influence policies.”