What Washington musician Yoko Sen describes as the “soundtrack of her life” is not one of the songs she wrote for the band Dust Galaxy, but the alarm of the heart monitor at her hospital bedside. “The constant rhythm of a cardiac monitor ticking like a time bomb reminded me every second that my life is finite,” she says.

When the U.S.-based Japanese artist fell ill in 2012 and had to spend weeks in hospitals, she found the jarring sounds there detrimental to her healing. “I thought it was torture, the cacophony of alarms, beeps, doors slamming, the squeaking of carts, people screaming, yellow alarm, red alarm, Code Blue.” At the time, it wasn’t clear if Sen would make a full recovery. She was connected to four different machines, and each emitted a different sound. Her sensitive ears were especially bothered by the constant beeping of her heart monitor. “It was a C note, and in the distance I heard high-pitched beeps when somebody fell out of bed — an F sharp, and I felt as if the sounds amplified my fear and feelings of helplessness.”

Sen recognized the so-called tritone. “In medieval times, it was known as the devil’s interval,” an unsettling tonal dissonance that used to be banned in churches. Jimi Hendrix wrote it into his intro to “Purple Haze,” Wagner into his Götterdämmerung, and film composers often use it to announce impending doom. Our bodies involuntarily respond to the dissonance with tension and unease. So why use such sounds in a place of healing?

When Sen asked her nurse why the heart monitor kept beeping, the nurse reassured her it was just a routine sound, nothing to worry about. “Sound is largely ignored in healthcare even though the aesthetics of it could have a great impact on our sense of wellbeing and dignity,” Sen realized. “We have made amazing progress in medicine, can operate on brains, but why do hospital patients still have to live with these medieval sounds?” As she started to question nurses, doctors and other patients about making changes, she found openness: “The most common reaction was, why haven’t we thought of this?”

When Sen recovered, she was determined to follow her new mission: to “humanize” hospital sounds. How does healing sound? Or love? Are there tunes that foster recovery? She founded SenSound in 2015, a social enterprise to reimagine the acoustic environment in hospitals, and she is about to announce a breakthrough. While the pandemic has interrupted some of her projects, including a long planned sound exhibition in Europe, she and her team used the last year to quietly work with four manufacturers of medical devices. One participant, Philips, is one of the world’s leading manufacturers of medical equipment. Roughly 80 percent of sounds in the ER come from patient monitoring, according to Sen, and Philips invited her to change the sounds of their most popular patient monitor. “Several months of further testing will be necessary,” Sen says. “I can’t reveal any details yet, but I can say that this will be a major step toward improving the hospital soundscape.”

From the stillness of her home 20 minutes outside of Washington, D.C., and surrounded by nature, 41-year-old Sen is addressing a massive, often overlooked problem. On average, a patient endures 135 different alarms each day, hospitals are often louder than a highway during rush hour and sleep deprivation is a common complaint.

The cacophony is not only bothersome but can endanger lives. Many caretakers and doctors suffer from “alarm fatigue” — they hear so many abrasive sounds that they simply ignore up to ten percent of important, lifesaving alarms. The effect of the clamor can be numbing, the exact opposite of an alarm’s intent.

At the beginning of her research, Sen first did what a musician does best: listen. “How about we ask the people who have to listen to these sounds every day?” she said. She and her husband, Avery Sen, an innovation researcher, interviewed hundreds of patients, nurses and doctors. “We first tried to understand, because you don’t just show up with a solution,” Sen says about the ensuing dialog between what she calls “the beepers and the beeped.” One doctor told Sen, “I never knew I could admit that I hate these sounds.” Sen’s goal: The sounds should be functional and safe but also gentle and respectful.

“Sound should be a public good, like hygiene or safety,” she says. Over the last five years, Sen and her husband have worked with renowned researchers at the Johns Hopkins Sibley Innovation Hub in Washington, D.C., Stanford University and the Vanderbilt University Medical Center. She was also an artist-in-residence at Kaiser Permanente and a fellow at the Kennedy Center.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Sen learned that manufacturers of medical devices don’t coordinate their soundscapes, and rather design the alerts louder and sharper than necessary for fear of being sued if someone misses an alarm. “They prioritize the safety and functionality of the devices, and they compete against each other, which is fine, but the manufacturers don’t take into account how these sounds affect the emotions of the patients, and whether the alarm for the heart monitor creates a dissonance with the beeping of the IV drip.” Sen quotes Florence Nightingale, who is often called the founder of modern nursing: “Unnecessary noise is the cruelest absence of care.”

Sen, who speaks with a very gentle, soft voice, seems to have been born with an uncanny sensitivity for music. She begged her mother for piano lessons when she was only three years old. The piano teacher told her mother to bring her daughter back when she was five, but Sen kept insisting. A picture shows the little girl on the stool in front of a grand piano, her feet far above the pedals. After moving from Japan to the U.S. in 1999, she continued her career as a professional ambient electronic musician, toured with her electro band Dust Galaxy and published solo albums.

For her mission to create a more soothing hospital environment, Sen found like-minded researchers in Elif Ozcan who leads the Critical Alarms Lab at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, and Joseph Schlesinger, an anesthesiologist at Vanderbilt Medical Center who also happens to be an accomplished jazz pianist. “We work together with experts from various disciplines because people could die if we make mistakes,” Sen acknowledges.

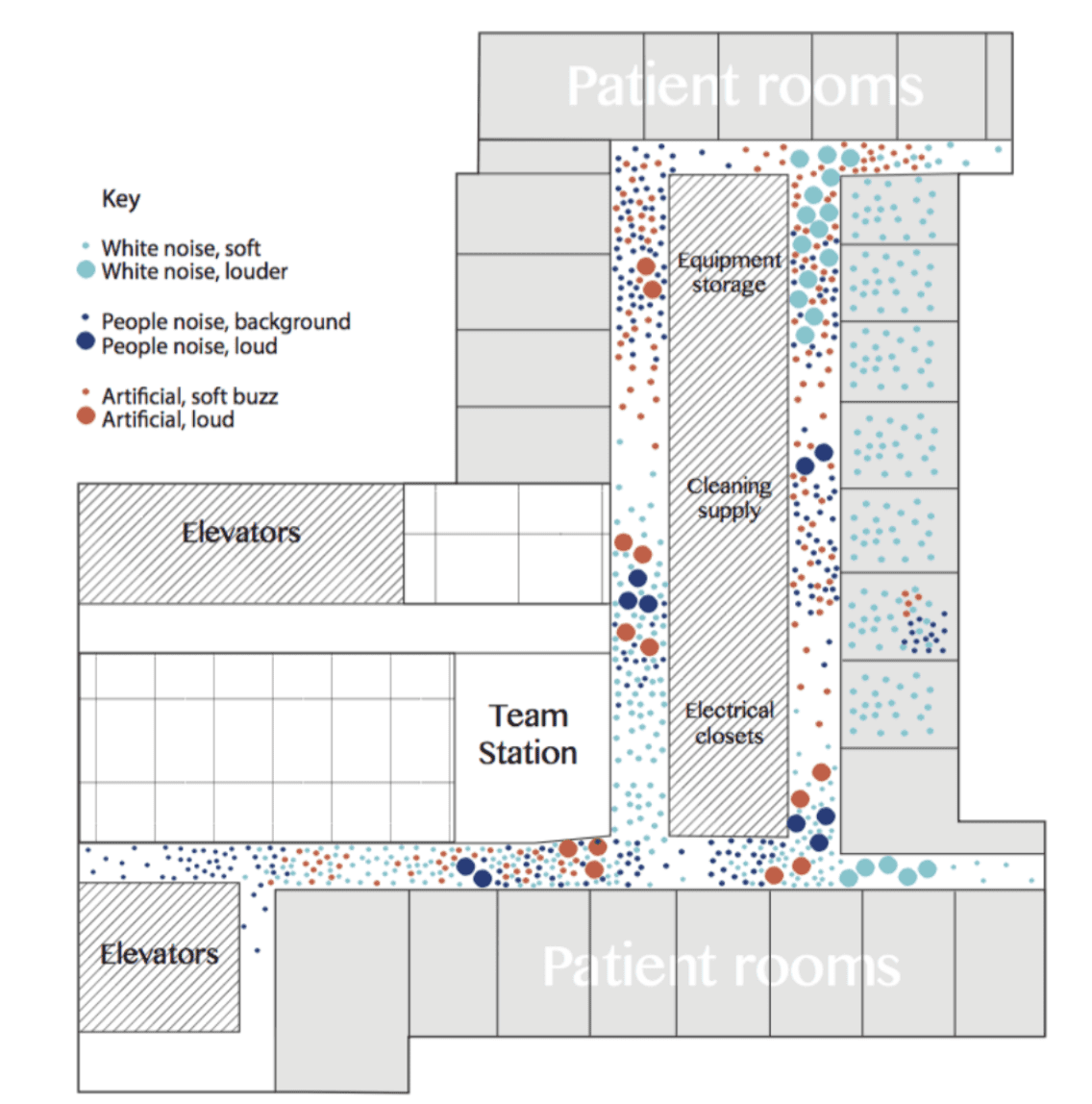

She also learned that everybody experiences sound differently. “One man was bothered by the nurses’ chat in the hallway, while his wife loved it because it made her feel less alone. Some prefer utter stillness; others experience stillness as overwhelmingly oppressive. It’s not just about the volume.” So, for Kaiser Permanente, Sen transformed a space in Colorado into an interactive area where people could try different sounds at the push of a button and report how it affected them. There was a common denominator: Almost all people found sounds of nature soothing.

Especially for hospice patients, Sen creates soundscapes that the patient can tailor with simple hand gestures. Movement sensors translate a wave of a hand into the sounds of ocean waves or a short symphony. Her gentle compositions remind the listener of waterfalls or rain drops, chimes or a rainforest in the wind.

One company, Medtronic, hired Sen to design new sounds for its homecare heart monitor, which is now available and used by more than 150,000 patients. “There were technical constraints within the project such that we were not able to change the timbre of the sounds, and it was only the melody we could help improve,” Sen says. “So the new sounds are more of an incremental improvement of the product’s functional sound, which are less harsh and more friendly to patients.”

The pandemic has increased attention for her work because during the last year, millions have died and suffered in hospital beds without the soothing presence of their loved ones. Sen shares that some researchers believe that our sense of sound is the last sense to leave us when we die. Remembering her grandmother who died surrounded by beeping machines, Sen asked people from all over the world, “What is the last sound you want to hear at the end of your life?” Many wish for the sounds of nature, the laughter of children, or the voice of a loved one, and Sen recorded their wish lists for her project “My Last Sound.”

What’s the last sound she’d like to hear herself? Yoko Sen giggles, hesitates, but then she admits what she recorded: her husband’s farting. “He’s farting a lot, it is a familiar sound for me, and it makes me laugh. If that’s the last sound I hear and I leave life laughing, that’s a beautiful vision for me.”