Though Fort Davis is located just sixty miles from the US-Mexico border, mild mountain summers have earned it the title of the coolest town in Texas. It’s in the heart of a sky island, a desert mountain range where migrating animals — and tourists seeking reprieve from the heat — can rest awhile among juniper trees and ponderosa pines.

Fort Davis is also on the cutting edge of serious science: tucked high into the mountains, just a few miles from the sleepy main street with its antique shops and quaint country courthouse, is the McDonald Observatory, a world-class center for astronomical research.

Visitors to the observatory can tour one of the largest telescopes in the world — the Hobby Eberly Telescope, which has its sights set on the edge of the universe. “We know the universe is expanding, and expanding at an accelerated rate,” McDonald Observatory Dark Skies Initiative Coordinator Stephen Hummel explains. “But we don’t know what’s causing it.”

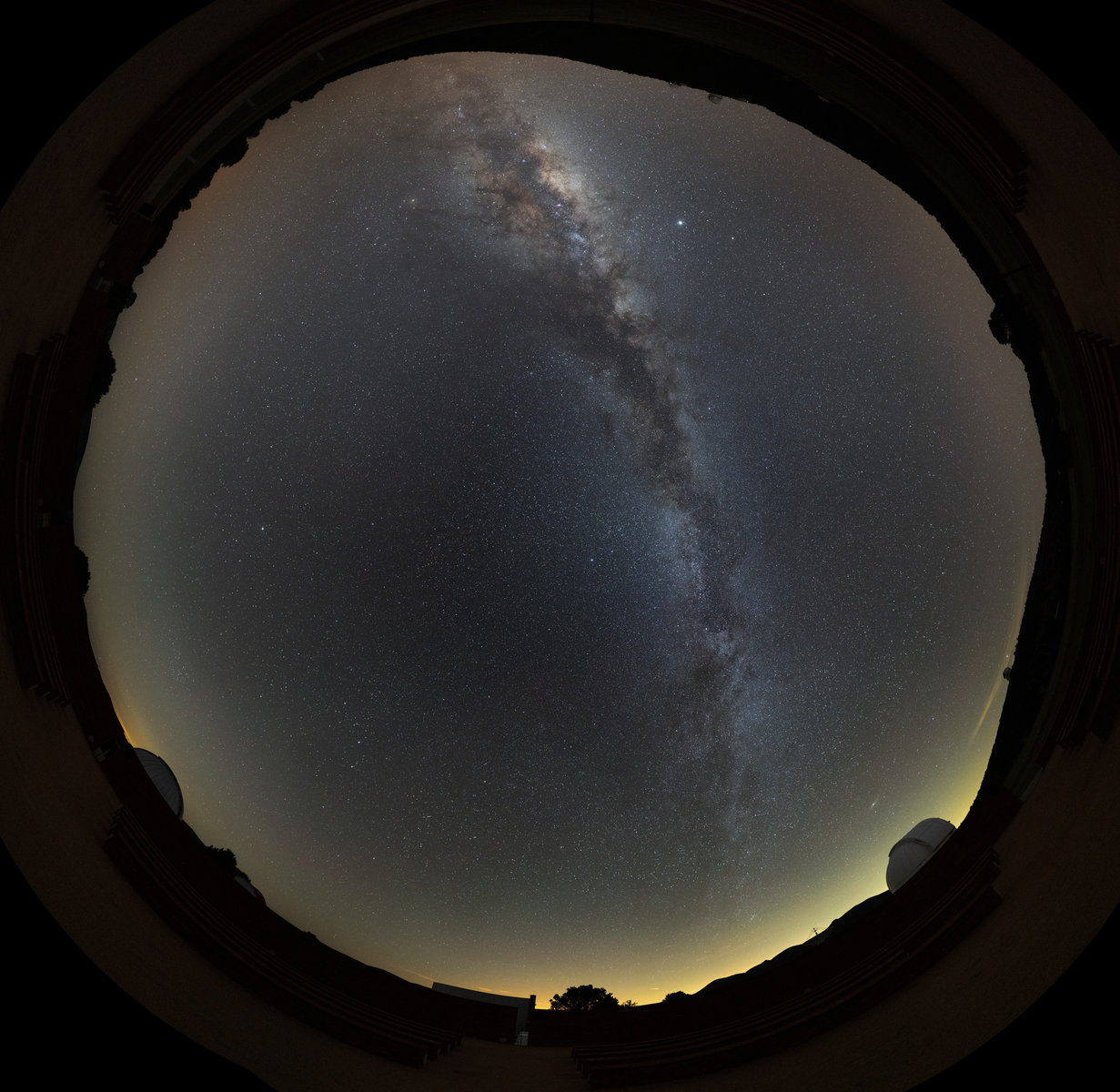

Scientists call whatever is causing the universe to expand “dark energy.” To study the phenomenon, scientists need the sky to be — as the name implies — very, very dark. “The dark energy experiment is the most vulnerable to light pollution,” Hummel says.

That’s because the galaxies the Hobby Eberly Telescope is tracking are so far away they emit very little light, which scientists measure in photons. Some register with only a handful of photons. In contrast, a lightbulb emits photons by the quintillions — a number with 18 zeros in it.

On a map of Texas after sunset, the region around the observatory is a dark hole in a bright spiderweb connecting the state’s major cities. That darkness is partly mandated by law: local towns have been required to adopt municipal lighting that minimizes light pollution. The other part, which Hummel is currently leading, involves convincing private citizens, school districts and businesses to get on board, too.

While the majority of his work is concentrated in nearby Presidio, Brewster and Jeff Davis Counties, he’s been trying to expand north — into the bright lights of oil and gas country.

Around an hour’s drive away from the observatory, the night sky is sometimes orange. “You look up and you can’t see anything,” says Chris Gafford, safety manager at Callon Petroleum. “When all those flares are going it’s like daylight out there.”

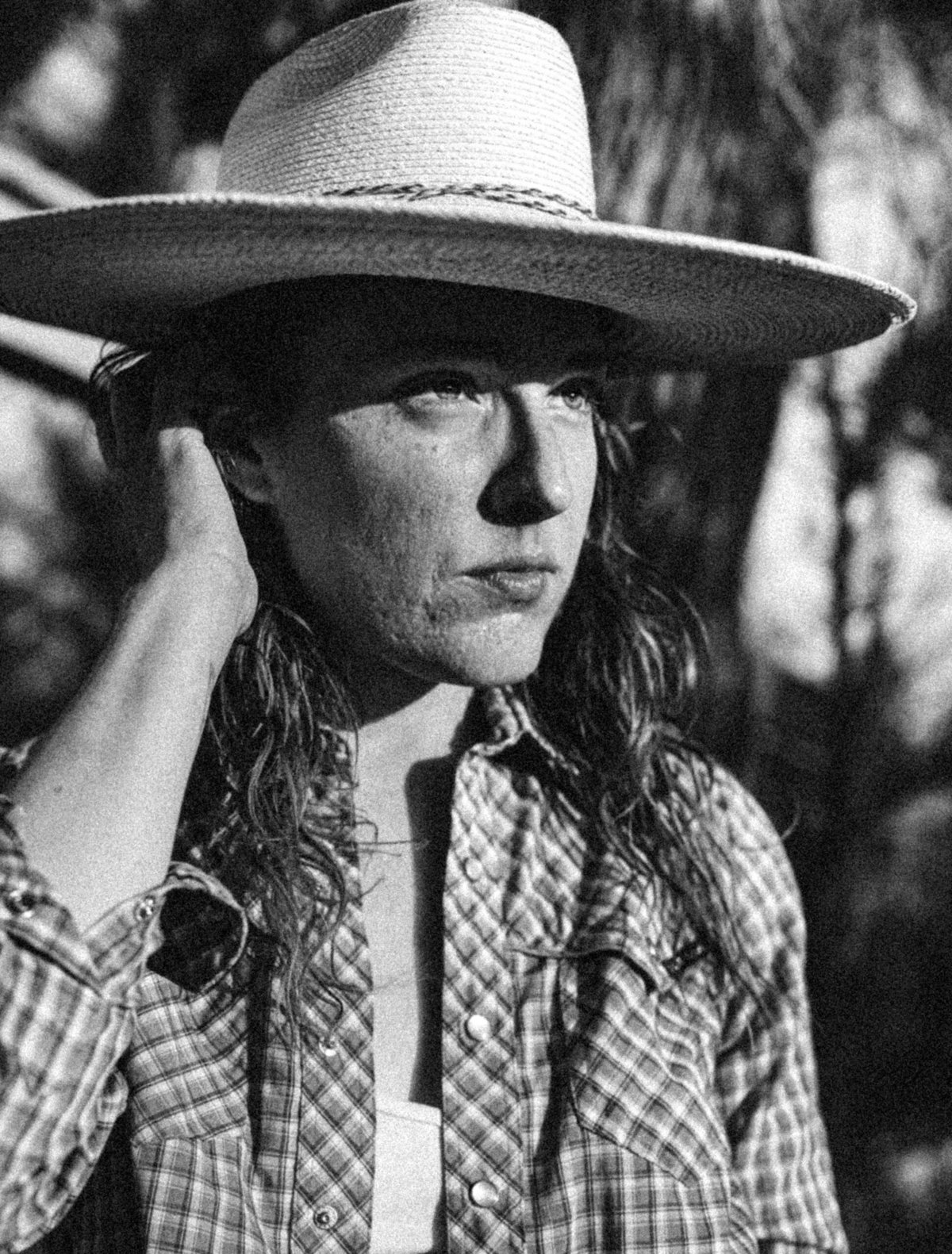

Gafford travels between the company’s facilities to make sure they’re safe for employees. This is no small feat in the oil and gas industry, which runs on fire and pressure and things that can explode.

Callon Petroleum’s properties aren’t staffed 24/7, but have to stay lit up all night in case something goes wrong. That’s where Hummel comes in: he and Gafford have been working together to make sure that the company’s night lights emit as little pollution as possible.

These facilities are located in the Permian Basin, an area of West Texas that produces nearly half of the country’s oil. By some accounts, the Permian Basin is the largest producer of greenhouse gases in the world.

In an act of great cosmic irony, the Permian Basin is adjacent to the Big Bend, which contains some of the most pristine wilderness anywhere in the country. In a ranking of the states by how much public land they hold, Texas scores a miserable number 45 — over 80 percent of which is located in the Big Bend region.

On top of unparalleled camping and hiking and boating, the night sky is a huge point of local pride. In 2022, after teaming up with three protected areas in Mexico, the Big Bend became the largest International Dark Sky reserve in the world.

To help bridge the gap between two polar opposite next door neighbors, Hummel — with the help of the Texas Railroad Commission (which, despite its name, regulates the oil and gas industry) and nonprofit Texan by Nature — has been approaching oil and gas companies like Callon to help spread the gospel of dark-sky friendly lighting.

The basic tenets of reducing light pollution are to point the light down, shield it from the top and use lower-intensity bulbs in warmer colors.

Counterintuitively, intense cool-toned lights — like the LED lights that institutions of all kinds have switched to in recent years to cut costs — make it much more difficult to see at night. If you’ve ever driven at night on the highway and been blinded by oncoming headlights, you’ve encountered this phenomenon firsthand.

“Brighter is better” has become an unspoken industry-wide motto, though it’s not just a marketing gimmick — many people really do prefer the whiter, brighter lights. “I think it’s just the human psyche,” Hummel explains. “We are creatures of the daytime, and we have evolved to see well under those conditions.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.But one of the important lessons Hummel teaches over and over again is that brighter light doesn’t actually make us safer. In fact, the opposite is true. Shielded, targeted bulbs help aim the light where it’s most needed, rather than diffusing it skyward; warm-temperature lights help the human eye adjust to be able to see into the shadows.

Oil and gas industry leaders who have had the chance to talk to Hummel almost universally see the collaboration as a win-win. Dark-sky friendly lighting makes facilities safer — and also helps the observatory’s mission to reduce light pollution.

Gafford has already noticed a difference in Callon facilities that have made the switch. “In the past, our approach has been to get a whole bunch of lights and blast things up,” he said. “But that leaves a lot of shadows.”

After working with Hummel, the company has opted for dark-sky friendly lights that are spaced evenly throughout each facility. “You get the right kind of lights and space them out in the right way and it’s actually better lit up,” he said. “There’s fewer dark spots, you don’t have guys tripping over stuff.”

In its early days — after an oil and gas boom in 2008 — the observatory’s project relied on good old fashioned door-knocking. Hummel’s predecessor, Bill Wren, would approach individual companies with educational materials and hope they’d see the light. Since then, companies like Callon have had a ripple effect on the industry.

One of the first major supporters of the program was the Apache Corporation, which sponsors the dark sky exhibit at the observatory. Texan By Nature, which helps businesses support environmental causes, stepped in to help Wren gain as much momentum in the Permian Basin as possible.

Jerrell Shircliff, formerly of Howard Energy Partners, pushed for change after watching a joint-venture company go dark-sky friendly at one of its compressor stations. Shircliff’s company wanted a piece of the action. “That’s how we got started, basically –– word of mouth through some of our counterparts,” he explains.

Howard Energy Partners quickly noticed a reduction in both light pollution and costs. Crew members also reported feeling safer –– Shircliff says that snakes are a common fear among folks called in to work at night. “The lighting is a big deal for everybody,” he says. “I don’t know about you, but I don’t want to step on a rattlesnake.”

When it comes to pollution of all kinds, the oil and gas industry doesn’t have a great reputation.

Over the past few decades, the industry has taken steps to try to bridge the gap — both in its production process and in contributing charitably to the communities it serves.

On the purely business end of the spectrum, companies have ESG scores, which quantify a company’s “environmental, social and governance” approach. These metrics can signal to investors how seriously companies understand their environmental impact and what efforts they’re making to mitigate harm.

On a more abstract level, the environment impacts everybody, whether they work on an offshore rig or in a corporate office — or are simply a living creature on our planet.

Talking about his own experience working in the industry, Gafford uses the analogy of a hunter’s relationship to the wild. “A lot of people think that hunters are bad people because they’re killing animals,” he said. “But if they’re out there doing it right — following the laws — they’re some of the biggest environmentalists; they want to protect everything.”

At the end of the day, the industry also has a vested interest in doing right by the landowners they work with — and the people who go to work in their facilities everyday, who call oil and gas country home. “I have to live here like everyone else,” says Shircliff. “I can’t just deplete everything around me.”

Being able to help reduce light pollution was a no-brainer for Shircliff, who has been interested in astronomy and stargazing from a young age. He recently took his kids on a trip to the McDonald Observatory to further explore the night sky.

While the observatory’s oil and gas industry was modeled on earlier initiatives –– like an effort by Dutch oil companies to protect birds in the North Sea –– the project has since charted unknown waters. “To my knowledge, there is nothing comparable,” Hummel said. “We have been contacted by people across North America about how to implement similar strategies.”

The goal is to keep up the momentum. “Awareness remains the biggest obstacle,” Hummel says. “But I am only one person. Partnerships with other companies and organizations are crucial for the program’s success.”

Though the individual changes may be small, the companies that have made the switch to dark-sky friendly lighting in West Texas are part of something huge — from the improved safety on the ground to the benefits to animals’ health to, of course, scientists’ evolving understanding of our world. Everyone involved is playing a role in answering some of humanity’s greatest questions — what role we play in an ever-expanding universe, as creatures made of stardust in one galaxy among billions.

Hummel puts it more simply. “I think a lot of astronomers are in astronomy for that innate sense of curiosity,” he says. “Who are we? Where did we come from? What’s out there?”