This story is part of Cool Project, a series about surprising ways cities are cranking down the heat in a warming world. Learn more about the series and the artwork here.

Along the tree-lined sidewalks of Tel Aviv’s Atidim Park, a business and commercial district in the north of the city, a curious new addition to the urban canopy arrived a few months ago.

Resembling something between a satellite dish and a ship’s sail, the structure known as LumiWeave is made of an innovative lightweight fabric designed to provide shade during the day and solar-powered lighting once the sun sets in the Israeli city.

“We want to incentivize walking and mobility,” says Gaby Kaminsky, managing director at CityZone, an urban innovation hub that is a collaboration between Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality, Tel Aviv University and Atidim Park, a district that sees 10,000 people pass through it every day. “If people have to stand in the sun, they’ll get all sweaty and just won’t do it. So we have to make the city a tolerable place even on hot days.”

For all its obvious cooling benefits, shade has often been overlooked by authorities when it comes to responding to extreme heat. But Tel Aviv, where peak summer temperatures can regularly exceed 40 degrees Celsius (104 Fahrenheit), has been shining a light on the importance of shade through a number of municipal projects as the world grapples with a rapidly warming planet.

The impact of shade on the body is unique. It’s well established that cities have microclimates known as “urban heat islands,” yet high air temperatures are not the only reason for heat stress. Research shows that standing in the shade can reduce perceived heat by 8.3 degrees Celsius (15 Fahrenheit) compared to direct sunlight, hugely mitigating health threats such as cardiovascular and respiratory disorders, heat stroke and even death. At least 363 Israelis died during heatwaves between 2012 to 2020, according to a study by Israel’s Ministry of Environmental Protection and Tel Aviv University.

Climate change will lead to more frequent, severe and prolonged heatwaves. Research published in the Communications Earth and Environment journal found 92 percent of the 165 countries

studied are expected to have extremely hot annual temperatures once every two years by 2030 under current national emission reduction commitments. In the pre-industrial era it was as little as once in one hundred years.

Tel Aviv is taking these figures and the role shade can play in mitigating extreme heat seriously. Prior to the launch of LumiWeave, the city developed “shade maps,” which document the shading of public space provided by things such as buildings, trees, colonnades and pergolas.

According to Dr. Or Aleksandrowicz, an assistant professor at the Israel Institute of Technology’s Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning who led the mapping initiative, the maps allow rare insight at the street and neighborhood-level. “We need more shade, but where and what?” asks Aleksandrowicz, who developed the maps with a small team over several months in 2018 and 2019.

The team used state-of-the-art analysis to create an indicator called the Shade Index, allowing for comparison of shade provision across the city on a scale of 0 to 1. They found classic indicators such as Tree Canopy Cover or Sky View Factor, while easier to calculate on a city-level, can misrepresent daily and annual variance in solar levels. To minimize costs, they also concluded that denser urban areas supplemented by tree planting may be a better approach to urban design than more open spaces, which require many more trees to provide similar levels of street shade.

“Trees are something we cherish and want to plant more of,” says Aleksandrowicz. “But if you plant them without space for roots, you will have a constant source of problems. Trees require much more infrastructure investment to make space for them.”

Precise mapping of urban trees can be useful not only for shade mapping but also for understanding the efficacy in tree planting for climatic purposes, according to a report published in 2021 by C40’s Cool Cities Network. In that regard, Tel Aviv’s shade maps could soon bear fruit: In January, Israel announced it would plant 450,000 trees in urban areas by 2040 at an estimated cost of NIS 2.25 billion ($676 million).

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.One problem Aleksandrowicz’s team highlighted, however, was that they only had 2.5D rather than 3D city-scale mapping of buildings and tree canopies, meaning that shade may have been overestimated since it was calculated as maximal during the entire day, irrespective of solar orientation and leaf density. They also called for universal regulations on shade provision that could be used for setting benchmarks.

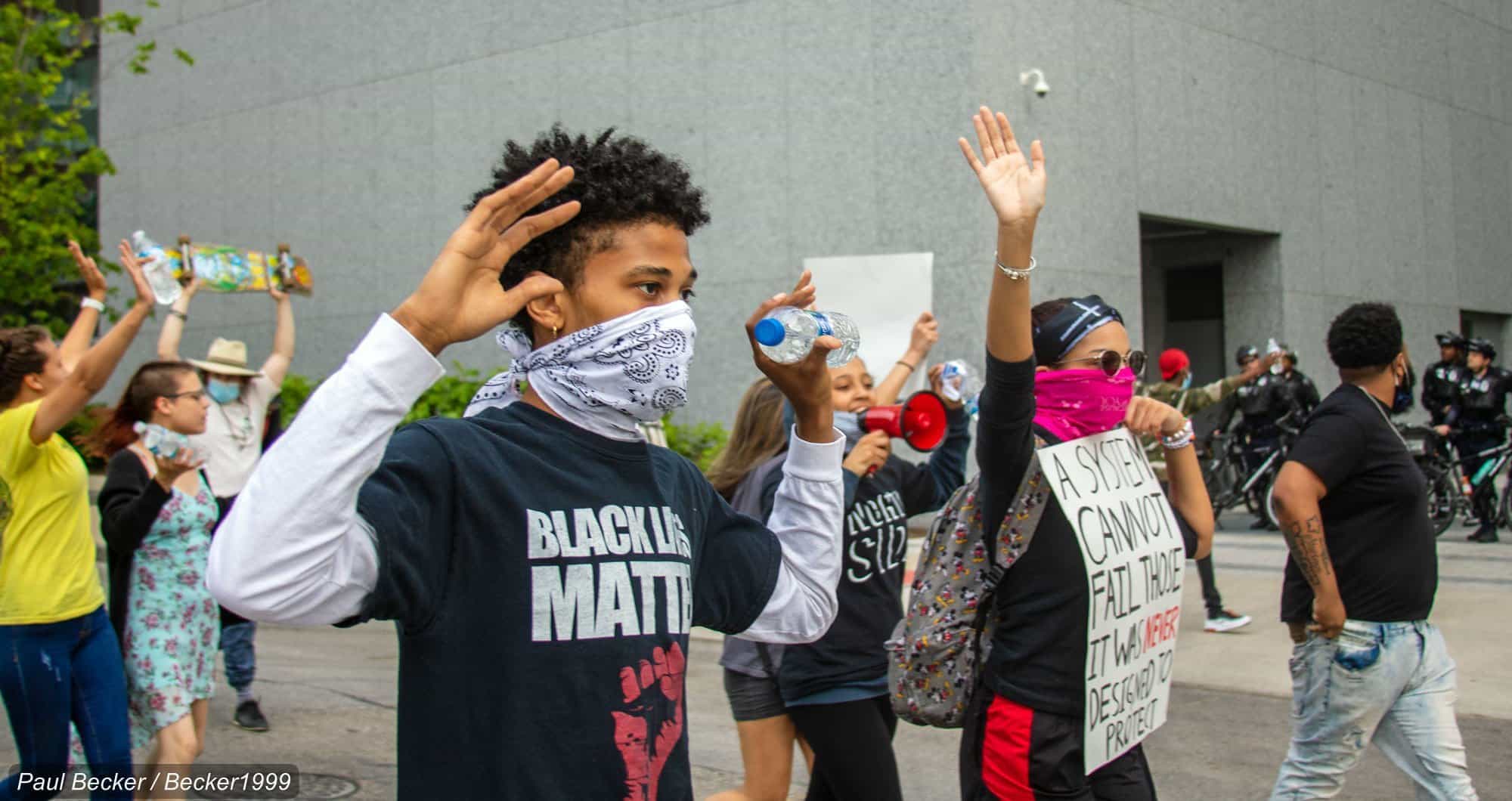

Sam Bloch, a New York-based journalist who’s in the process of writing Shade, a book exploring shade’s relationship to climate and inequality, says that modern municipalities have tended to overlook shade because of technology such as air conditioning and smart glass that blocks sunlight, as well as the dominance of cars, whose need for wide roads narrows the potential area for sidewalks and gives less space for trees.

“But shade has this special value,” says Bloch. “It’s where people want to be on hot days. It maintains common spaces and social connections.”

Shade, too, can play a role in countering inequality. Bloch says there can be 10 to 15 degrees difference in air temperature between neighborhoods in the same city due to infrastructure. “There’s a distinction between public and private shade,” he says. “And there tends to be shade poverty in poorer areas. Cities should react to this.”

Across various civilizations, shade has played an important role, according to Bloch. Before the idea of the street tree, the Roman Empire often had arcaded walkways in towns. Historic Middle Eastern and North African settlements, meanwhile, had very narrow streets, allowing buildings to create shade.

Nowadays, while Tel Aviv is is leading the way, Bloch says, others are taking different tacks: Vienna offers citizens a grant to install exterior window blinds and awnings; Phoenix is turning its black asphalt streets gray, using a special sealant that reflects rather than absorbs the desert sun; Melbourne supports its tree shade through greywater recycling; and Singapore has a network of canopy walkways for rain and sun protection, as well as regulations stating that at least 50 percent of public areas must be in shade during the day.

Back in Tel Aviv, the municipality has made LumiWeave orders for 10 more locations across the city. The fabric, created by designer Anai Green, is embedded with solar, organic photovoltaic cells. It requires no electrical infrastructure, saving on costs, and can provide lighting at night for up to three days without sun. But that shouldn’t be an issue as Tel Aviv has an average of about 300 sunny days a year.

Alongside LumiWeave, CityZone is working with other Tel Aviv-based start-ups such as SolCold, which has developed a paint — to be piloted later this year — that actively cools down when exposed to the sun, in theory reducing temperatures to lower than shade. BioShade, meanwhile, uses hydroponic systems to grow shading plants by up to 10 inches a day, helping to accelerate and simplify the process of tree growth.

“We don’t have time to waste,” says Aleksandrowicz. “We need to use the knowledge we have now for large-scale implementation of shade.”