On October 8, to celebrate five years of publishing, Reasons to be Cheerful will host the biggest event we’ve ever staged: a live variety show at New York City’s Town Hall. Alongside a full slate of wacky and whimsical acts, the show will include a few moments in which we bring to life the kinds of solutions stories that RTBC is all about.

One of those moments will highlight the Trust for Public Land’s Community Schoolyards Initiative. Over the past 30 years, the project has transformed 350 schoolyards across the US into amazing environments for learning, recreation and community. These spaces benefit the school during the workday, and after hours, they become a park for the entire community to enjoy.

We spoke with Danielle Denk, senior director of the schoolyards initiative, to learn more.

How did Community Schoolyards come about?

It began way before my time: 30 years ago in Newark, New Jersey. We were working with community gardeners to help them establish community gardens around the city. Some of the gardeners came together and said, “We also don’t have any playgrounds or parks for our kids to just go and enjoy, and there’s no open land here. But we have an idea: Can you help us unlock the doors of the school so that we can use it after hours for our kids?” We went to the school, and the school said their facilities were decrepit and had all these problems. So we asked, “What if we transformed these spaces and then opened them?”

For the past 30 years, the community has been able to enjoy that beautiful space, and it became a model that really inspired this movement. It should be the norm, and that’s what we’re working toward. Kids need trees, they need a place to be outside and to know that it’s theirs. This transformation of the space outside their school is unlocking that connection to nature that’s so vital.

What are some of the elements you’re bringing to these spaces, and what do the before and after look like?

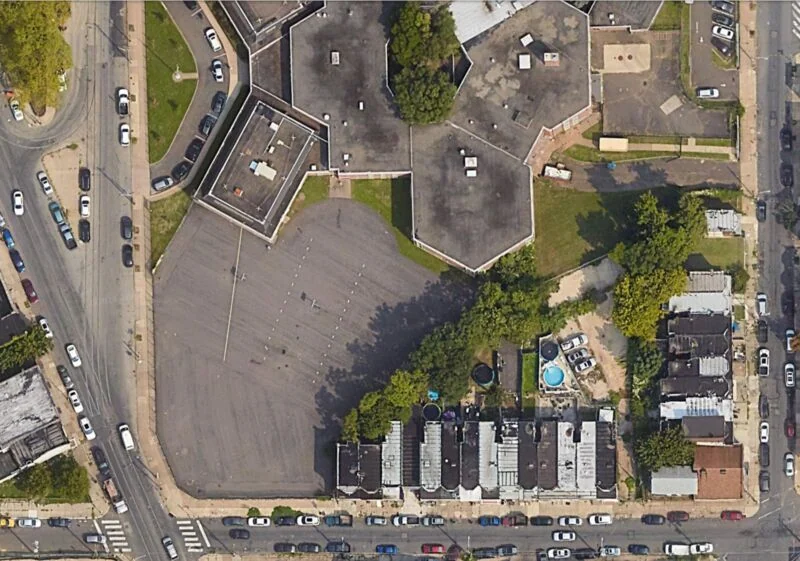

Before, it’s usually a sea of asphalt that’s deteriorated and cracking. You have chain link fencing around the schools, and really nothing about that outdoor space is welcoming or beautiful or inspiring.

We work with the students, and they come up with what they want to see. A multi-purpose field is very popular because they want to do gymnastics and football and soccer, and they want to be able to land and not skin their knees and arms. So spongy ground is really popular. They want to be able to run; tracks are very popular. Garden spaces, too. It’s the students who want gardens, not just the teachers.

More trees, more shade — that’s a big concern right now. As climate change is making everything hotter, our schools are also becoming hotter because the asphalt is a heat sink. We’ve seen studies that show that when you have a very dense forested environment, you can cool the temperatures by as much as 17 degrees. When you think about the heat going up above 90 for many days, up above 100 for hundreds of days in Arizona, it’s a crisis, and schoolyards are part of the solution.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.You mentioned that the students are very involved. What does that process look like?

We do a process called participatory design. It’s usually about a semester long. We’ll go in as educators and work with a team of students. Those students are the design team, and they’re learning all about what it’s like to see and think like a landscape architect. They’re understanding the climate science, urban design — things that most students wouldn’t get exposed to until college.

The process brings that learning to life: When we talk about geometry, well, they can go outside and measure what a basketball court would feel like in that space and realize, “Oh, that’s not gonna fit, what can we do instead?” They have to come up with creative solutions. They’re really thinking about the space in critical ways.

When we come back to actually do the design after a couple weeks of learning and exploration, they’re so wise and so creative and they really take it seriously. They want to make their schoolyard as amazing as possible, and they’re working really hard to do it.

How do you build the bridge between the school and the community?

The students are the main designers but they’re also sort of ambassadors, especially if they’re older. If they’re in middle school or high school, they can even go out and conduct surveys. We can bring them to community-based meetings so the students are the ones explaining everything — it’s an awesome opportunity for them.

They’re also bringing their parents to the table. That’s really important: So many schools are in gateway communities, in places where there’s multiple languages, so the school is serving as a hub to make people feel welcome. For people who are newly arrived in this country, the students are often the ones who have this amazing responsibility of helping their parents access resources. When we can also have those parents involved in the design conversations, it gives them another kind of stake in the ground that’s so important.

So the students are essential to making sure that community connections are authentic, that they are woven throughout the process. In addition, we’re asking how the community will use the space. Often the community will review the students’ designs.

This program started in the Northeast. What has it been like to figure out how to implement it elsewhere?

That’s what has been so fascinating in the last 10 years as we’ve been taking it to other places. We recognize that it’s our process that is really important and that the actual materials, the amenities, all those things are secondary. If you follow through that same process— the ideas, the climate adaptation, the stewardship, the community empowerment — all that will come. It’s about having an inclusive design process, having intentionality and lifting up the voices of the folks who are involved and most impacted by these spaces in a positive way.

Have there been times when a team of students or a community wanted something that surprised you?

There are some great stories coming out of our work with the Coeur D’Alene Tribe in Idaho. There’s a long history of making canoes, so the students said that in their schoolyard, they wanted to have canoes. You wouldn’t hear that in New York City. Of course, it’s not going to be a canoe from the REI down the street — this would be a canoe that’s sourced in the right way with the lumber and carved out meticulously over time. So we’re going to start the process of creating canoes before the schoolyard even breaks ground.

Similarly, we’re working with the Crazy Horse School on the Pine Ridge Reservation. There is a really important connection between the youth and the Lakota elders, and having a place to hear the stories of their ancestors is vital. So we’re creating listening and storytelling spaces for the community that will really center the elders.

As we collect stories from the elders through the process, all these amazing plants are mentioned. We’ll be planting them so that there’s this tactile ability to not only just tell the story but also to bend over, pick the grasses and show the seeds and talk about the traditions that come from harvesting. We’re making space for that deep listening — that’s what makes it so that the space is relevant and will impact future generations.

A student will be presenting with you at our upcoming variety show. Can you tell us a little about him?

I met with Ismael Shayaan and his teacher and he was so excited. He showed me all the different areas; he was very excited about being able to play soccer, and that when he plays soccer, it’s gonna be safer. But he was also excited about how there are going to be chess tables, and he knows that some of the community members will come and play chess.

There was one tree that looked like maybe it got a little knocked during construction. He was worried about the tree. He’s definitely already a landscape architect in training.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.