Though Jacob Chavez grew up around family members who spoke Cherokee — his grandmother was fluent and his father could understand the language — the 23 year old didn’t learn it as a child.

Now, as a young adult, the Tahlequah, Oklahoma, resident is taking part in a unique program to train Cherokee Nation citizens and those interested in Cherokee culture to become highly proficient in the language by paying them to study it. It’s one that is quickly disappearing.

“It’s in my family and I would like to kind of like, build it back and strengthen it back amongst some of our younger generation that we have and then, it’s just a passion that I’ve had — probably since senior year of high school,” Chavez says. “I just wanted to have that part of my identity and I’ve just been working on it ever since. And I took a couple classes in high school and in college and then now I’m in this program.”

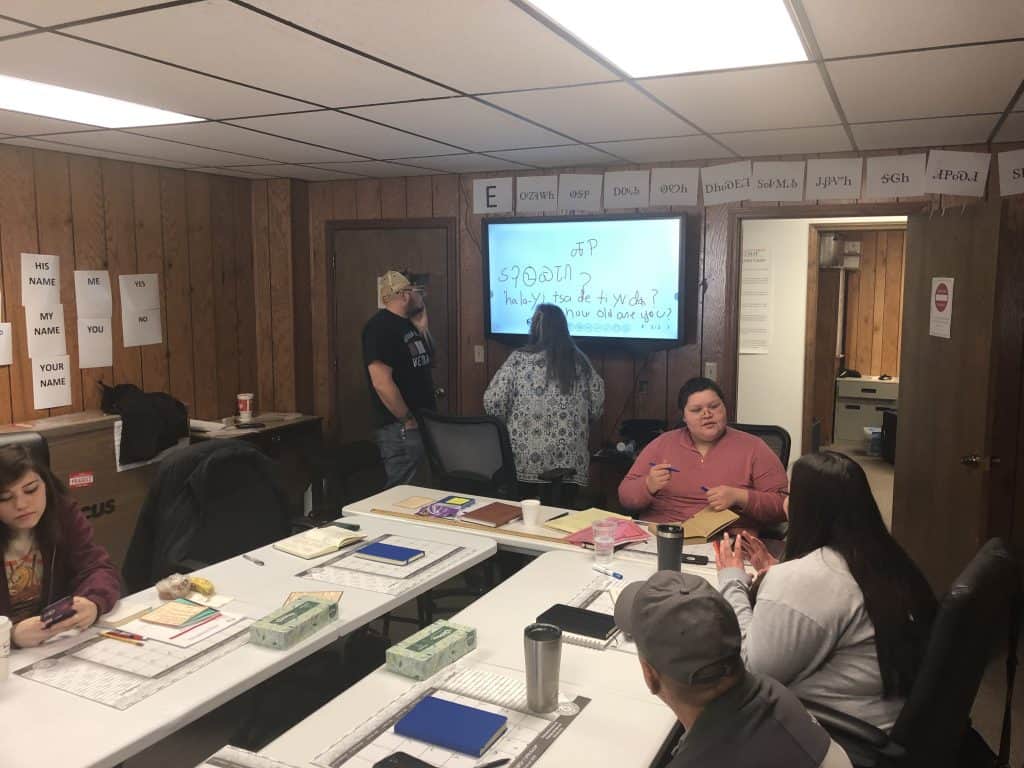

The Cherokee Language Master Apprentice Program is an immersion program for adult Cherokee language learners. The program is geared for novice language enthusiasts, and it is intense: the 40-hour-per-week program runs for two years. Participants are paid $10 per hour, says Howard Paden, Cherokee Nation Language Department executive director.

“It’s not a whole lot, but what we have learned is people who have been really dedicated to learn the language — you have to have that many consecutive hours so they have to have the ability to live and continue to put some groceries on the table and that sort of thing,” he says. “So, it’s worked out really well. You know, we haven’t expected to make them be rich by any means, but we do want them to survive while they learn the language. And so that incentive has allowed people to focus just on the language instead of other things.”

The program, which started about six years ago, has grown. It went from having four students per year to 16, so at any given time, there will be 32 participants taking part in the two-year program when fully filled, Paden says.

For the Cherokee Nation — the largest tribe in the United States by population with more than 380,000 citizens worldwide — the program is taking on extra importance. There are about 2,000 fluent Cherokee speakers, according to Paden, and in the last year, more than 100 have died, some due to Covid-19-related illnesses.

“Right now, we’re losing roughly five percent of our speakers per year,” Paden says. “But we know that it takes quite a bit of time [to learn the language] and it’s not happening organically in our communities anymore.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Losing so many fluent elders is one reason that the tribe placed them among the top of their Covid-19 vaccination list. According to the tribe, since receiving the first distribution of vaccines on December 14, the Cherokee Nation administered more than 6,500 vaccines, including to about 900 Cherokee speakers, as of January 19.

Due to the pandemic, the coursework for the Master Apprentice Program is taught online, something that Chavez says has been difficult, but he is making work.

“I’m a very in-person type of learner,” he said. “I can’t really do this technology interface kind of stuff, but I’ve had to adapt and I’m willing to do that. I want to do whatever I’ve got to do to learn and so it’s just kind of a means to an end, really. If I’ve got to use a laptop and get on Zoom, I’ll do that. But I’d much rather be in a classroom. I think we all would. But this is the world we live in and it is what it is.”

The Cherokee Nation looked to several different initiatives to help guide them when creating the Master Apprentice Program. They looked at a program within the Sac and Fox Nation, also based in Oklahoma, as well as the Euchee (Yuchi) and even the Māori from New Zealand.

The Cherokee Nation’s reservation encompasses 14 counties in northeastern Oklahoma, including parts of Tulsa County. There are ongoing discussions to possibly host a class at one Tulsa high school, though Paden is unsure where that stands now with the pandemic — both the high school and the tribe are doing most things online now.

Chavez believes that a tribe can’t have culture without language, and so that’s why he focuses on the future and learning the language.

“Those two things are just kind of joined, and if you lose our language and you still have culture, it’s kind of just a history, almost, because language is so ingrained inside of a culture,” he said. “You know, there’s names for all this stuff like games and ceremonies and things like that. You need the language to use all that. And so it’s vital for our nation and other nations that struggle with their languages… we’ve lost that connection between our elders and our youth because mainly they didn’t want to pass on language. [T]he consensus is that we’re losing it, so we’re trying to build it back now. It’s really important for us.”

This story originally appeared in Next City. It is part of the SoJo Exchange from the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous reporting about responses to social problems