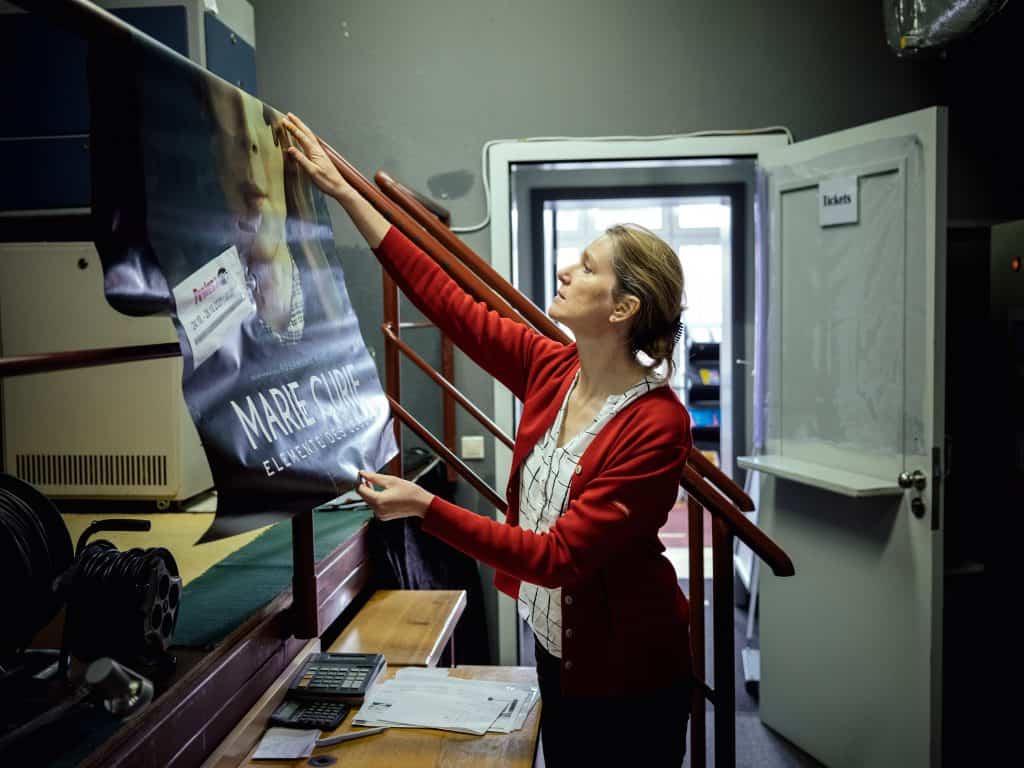

Back in early 2020, when Karen Schneeweiss would arrive home from her job at a small German theater, she would often have to answer some 50 emails from her other jobs at two sailing schools. An animated actress, Schneeweiss, 49, took on these extra gigs to help pay her monthly bills. Pulled in multiple directions, she believed she would never have the time to truly focus on her acting.

Little did she know that she was about to receive a prize that would change all of that: a fixed monthly income of 1,000 euros that would allow her to pursue her creative dreams.

Schneeweiss receives a basic income from the German organization Mein Grundeinkommen (My Basic Income). Founded in 2014, the initiative organizes periodic raffles to randomly select people — regardless of age, background, current income or nationality — to receive regular no-strings cash payouts for 12 months. Mein Grundeinkommen’s founder Michael Bohmeyer got the idea for the raffles after selling his successful tech startup in 2014 and receiving a monthly guaranteed income of 1,000 euros as a result. Having a constant flow of unconditional cash made him feel less stressed and more creative. He started wondering how he could share his experience and, in 2014, started to crowdfund basic incomes for others.

Since then, 843 mostly German citizens have received a basic income from Mein Grundeinkommen and more than 2.7 million people have signed up for the organization’s raffles. Many are people like Schneeweiss — folks who aren’t poor, but who nevertheless struggle to achieve their dreams amid ever intensifying demands from jobs, families and life in general.

The idea of a universal basic income is nothing new. For centuries, philosophers, economists and politicians have dreamt of a society where people could work less while maintaining a decent standard of living. Since the 1970s, small-scale experiments in various forms have been conducted in Finland, the Netherlands, Spain, Brazil, Canada, the U.S. and South Korea. Mein Grundeinkommen wants to add a new chapter to the existing body of research with a rare example of community-led, completely unconditional basic income.

With global crises putting pressure on societal supports, the work suddenly feels timely. Last year, researchers from the OECD published a report calling for bold new investments in long-term wellbeing. “We need to look beyond maximizing people’s wellbeing today,” the OECD writes, and address the “storm clouds that gather on the horizon, mainly from environmental and social challenges.”

The OECD found a global increase in wellbeing over the last ten years, defined according to over 80 indicators in categories from health to income to civic engagement. But it also found that this rise will not be enough to sustain people’s wellbeing in the long term. Almost 40 percent of the households are still financially insecure. The average death toll from suicide, alcohol and drugs is now six times higher than the death toll from homicide. And support networks are under strain — people spend an average of only six hours per week interacting with their families and friends, a tiny fraction of what they spend working, and half an hour less than ten years ago.

Schneeweiss recognizes some of these trends in her own community in a small village in the county of Brandenburg, an hour outside of Berlin. She says people spend less time with each other, take on several jobs at the same time and are more afraid to lose those jobs than they used to be. “I grew up in the DDR, where it was very different and certainly not only positive,” she says. “But money was not so important then and people had a lot of time left to spend with friends. Today you are restricted in your freedom by the constant need to earn enough money to pay your living.”

With her basic income, Schneeweiss can now turn down some work that she previously would have accepted only for the money. The basic income helps her step off the treadmill that defined her previous work-life dynamic and focus on what she finds important in life.

This is exactly how Michael Bohmeher, the founder of Mein Grundeinkommen, thinks a universal basic income should work. It wouldn’t cost much, he believes, as it is simply a redistribution of the available money, which would be acquired through taxes. Critics contend that free cash would encourage people to stop working entirely. But previous experiments in Finland, Canada, Iran and India show that basic incomes can actually motivate people to work.

This was the case for 33-year old Sebastian Weigel from Hamburg. He had just quit his job at a real estate company when he received the email from Mein Grundeinkommen. “When I first saw the email, I thought it was spam,” Weigel laughs. “Because that’s always the case, right, if someone emails you saying you won money? But then I saw the email was from Mein Grundeinkommen.”

Weigel also works at a laboratory where he analyzes Covid-19 samples. Instead of working less, he actually now works even more hours than he did before. “Yesterday my shift took about 13 hours,” he says. “I don’t work because of the money. Due to the coronavirus we have a lot of work to do and I don’t want to let my colleagues down.”

The basic income helps him to think about what he would like to do in the long term. “I have this idea in my mind to start a little shop somewhere in Hamburg where I would sell products from small creative entrepreneurs. My sister is working on some clothes and I have some other friends who create art. Without the basic income, I wouldn’t think about starting something like this. It gives me a free mind.”

Experiments have shown how a basic income can change the lives of people whose situations are dire, but research into its effect on the wellbeing of people who don’t desperately need it is scarce. “We do have some indications that as a result of the basic income wellbeing increases, less people are depressed and people become more healthy,” says Susann Fiedler, psychologist and economist at the Max Planck Institute. “But research has mostly been done with people who are in need, who go from nothing to having something. So the fact that school enrollment goes up and crime goes down in one village in India doesn’t say much about the results in Germany.”

In an attempt to remedy this, Mein Grundeinkommen successfully crowdfunded a research project in collaboration with the German Institute for Economic Research, University of Cologne and the Max Planck Institute. The researchers will follow 120 people receiving 1,200 euros per month for three years unconditionally, and compare their results with a control group.

In the meantime, Schneeweiss is allowing her dreams to take shape. She stands in an empty hall that she used as a theatre before the pandemic; it reflects a certain peacefulness and untapped potential. She talks about the mental space the basic income has given her, how the pandemic slowed down her life, and how new ideas emerged, such as transforming a few rooms in her house into a community theater, making a play of her grandmothers’ letters from the Second World War and volunteering in a local hospice.

The basic income helped her to get closer to herself, she says, and thereby indirectly closer to the people around her — an effect that is shared by other recipients. Bohmeyer often makes the comparison with small children, whose wellbeing is strongest when they are in a safe environment. “They are allowed to cry and to fail, things we are not allowed to do anymore as adults.” In a time of increasing uncertainty, Mein Grundeinkommen might have found a way to bring a sense of security back to people’s lives.

Photos by Florian Bachmeier. Florian Bachmeier (born 1974) studied photography at the Escuela de Artes y Oficios in Pamplona and new and contemporary history at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich. As a documentary photographer, he has been working on long-term projects with a focus on Eastern Europe for many years. His work has received several awards, and been published in numerous magazines and journals and presented in international exhibitions.

This story was commissioned by the Solutions Visual Journalism Initiative and produced by Are We Europe.