In a small village in the state of Gujarat, India, Amari Kanti Parmar stands in a spacious room admiring a dazzling selection of 50 sarees hanging neatly on a wooden stand. She plucks a teal saree from the rack, pure silk with a paisley pattern, and hangs it on her right shoulder, staring at the full-length mirror on the wall.

“Perhaps a lighter shade would work better,” she muses. Her eyes quickly land on another: a mustard-colored nine-yard in Chanderi silk with a luxurious golden border. “Yes, this would be fit for the morning function at my sister’s wedding,” she tells Kamala Arvind Chauhan, standing next to her to help her decide. “I agree,” Chauhan says and moves on to suggest an additional maroon saree with zari embroidery for the wedding dinner.

Parmar neatly folds both the sarees, stowing them in her sling bag as Chauhan documents the items in a long notebook. No money exchanges hands. “I’m sure you’ll get a lot of envious looks at the wedding,” Chauhan teases. “Don’t worry if you are a little late returning them.”

With a spring in her step, Parmar steps out of Chauhan’s home.

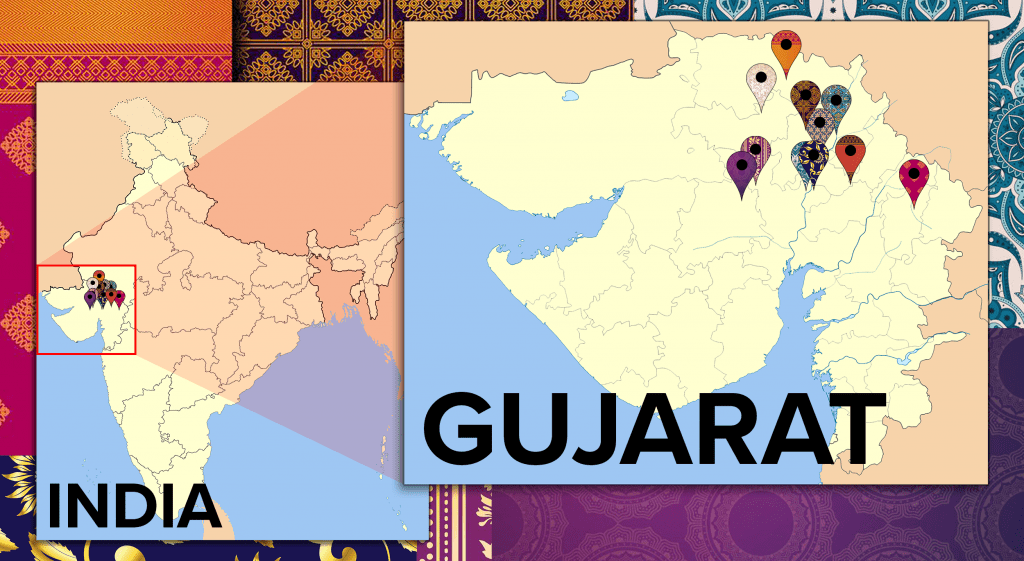

Launched by the Ahmedabad-based NGO Gramshree Trust in December 2020, this saree library in the village of Chadotar is part of a growing network across the state. One of the latest additions to Gramshree’s lineup of 11, eight of which are in rural areas like Chadotar, the libraries provide access to top-end sarees for women who cannot otherwise afford the items critical to every Indian woman’s ability to participate fully in social life.

Living in a small community, Parmar is invited to at least six to eight weddings each year, where her absence could strain important relationships. At the same time, the pressure for women to dress well is high. Wedding rituals in India last three to four days and women are expected to wear a new outfit for every function. Quality attire is an investment in social capital. Other social events such as births and mundan ceremonies — the ritual shaving of a toddler’s head — also require festive attire that Parmar is unable to buy with her day laborer’s income of 3,000 rupees (about USD$40) per month.

In the past, Parmar purchased used party-wear sarees for 100 or 150 rupees ($1.37 or $2.06), which were mostly worn out and lasted just a couple of washes. But now she regularly makes trips to Chauhan’s house to admire the extravagant selection, retailing between 2,000 to 20,000 rupees ($27.50 to $275), and has earmarked a few for upcoming events. There is no renting fee; borrowers must only have the saree drycleaned, which costs 50 rupees (70 cents), a small fraction of the price of purchase.

Overflowing wardrobes put to use

The saree library concept was developed nine years ago by Vandana Agrawal, a trustee and board member of Gramshree, which works to support women in becoming economically self-reliant by training and employing them in textile arts.

“Whenever I went to the Gramshree centers, women working there surrounded me and appreciated my dress or accessories. When I told them they were looking nice too, I got big smiles,” she says.

At the same time, Agrawal knew plenty of wealthy women with overflowing wardrobes of sarees they were unable to use. Typically in India, women buy several showy sarees for their trousseau — a collection of outfits “suitable for a new bride” worn in the weeks following their wedding. Most women have little use for these dresses a few months after marriage, so each of Gramshree’s libraries stock 30 to 50 such pieces.

Ami Udeshi, a donator to the library from Ahmedabad, prefers to donate her sarees to the libraries instead of giving them away to one woman because it “widens the scope of their use,” she says.

The first library premiered in the winter — wedding season — of 2011 at a Gramshree center in Ahmedabad. Though it was originally launched just for the women working with Gramshree, word of mouth spread quickly, eventually leading to the libraries’ doors opening to the wider public.

Libraries are set up at Gramshree’s centers, village temples and people’s homes — like the library Chauhan manages out of her spare room in Chadotar. Chauhan knows most of the women in her village already and keeps the library open for two hours every evening for borrowers to stop by. The library operates on a trust-based system and so far every item has been returned. “I love welcoming women into my home and chatting with them,” she says.

“Spending on themselves is their last priority”

Asha Suresh Makwan lives in Ahmedabad and works as a domestic helper for about the same income as Parmar. “I don’t have a single festive saree, since I can’t afford one,” Makwan says. “But I love the selection at the library and borrow quite often.”

Makwan likes to spend whatever she can save from her salary on her children’s needs. Despite doing all the cooking at home, the food she puts on the table caters to her family’s liking. She foregoes her favorite dishes like kadhi, a sweet-sour Gujarati curry with chickpea flour and yogurt, that her family isn’t fond of. “I prepare what my children and husband like to eat,” she says.

“Women who are underprivileged do not give any significance to their desires. Spending on themselves is their last priority,” Agrawal says. “The saree library is just one of the catalysts to change women’s mindsets about themselves. We want them to understand that the society will never pay attention to their needs and desires if they don’t do it themselves.”

Gramshree’s other programs for its employees, such as talks and camps on health and nutrition, all have a similar aim: to help women understand their physical, sexual and mental health and fulfill some of their own desires.

So far the Gramshree saree libraries have served over 4,700 women across Gujarat. Due to high demand, Gramshree’s sister organization Manav Sadhna also opened three in Ahmedabad. While saree libraries do not yet exist in other states — save one retail shop in Kerala that distributes free designer wedding wear — Agrawal is quick to point out that the opportunity for growth is infinite. “The library is easy to maintain and the idea is easily replicable across the world,” Agrawal says. Women in India are certainly not alone in withstanding high pressure and social or economic consequences stemming from expectations around attire.

Parmar associates the sarees she borrows with joy. “Dressing well is important to me — so what if I earn so little?” she says. “I feel good and confident when I wear a new saree.”

“So many people appreciated the sarees I wore at my sister’s wedding,” Parmar says. “I told them: We have a saree library where I can get something new to wear every time I want to.”

Photos by Ashit Parikh