When Randolph County’s $242 million Riverstart Solar Park is completed in 2022, it will be Indiana’s biggest. Thousands of photovoltaic panels covering 1,400 acres of rural land will generate enough clean electricity to power 36,000 homes.

Massive solar farms like this can be a touchy subject with locals. So, in the lead-up to the project’s approval, county legislators ensured the developer would be a good neighbor, with measures to avoid glare from the panels and mandated setbacks from roads and highways. And then they took it one step further, requiring the planting of pollinator-friendly plants like wildflowers and clover, in addition to native grasses. It was the first such mandate in state history.

The requirement will ensure that Riverstart will benefit the very land it is situated on. “It will help the bees, which are under attack,” said Michael Wickersham, one of the three Randolph County commissioners who approved the zoning ordinance. “Adding the pollinator [plants] back into the ground is nothing but a win-win.”

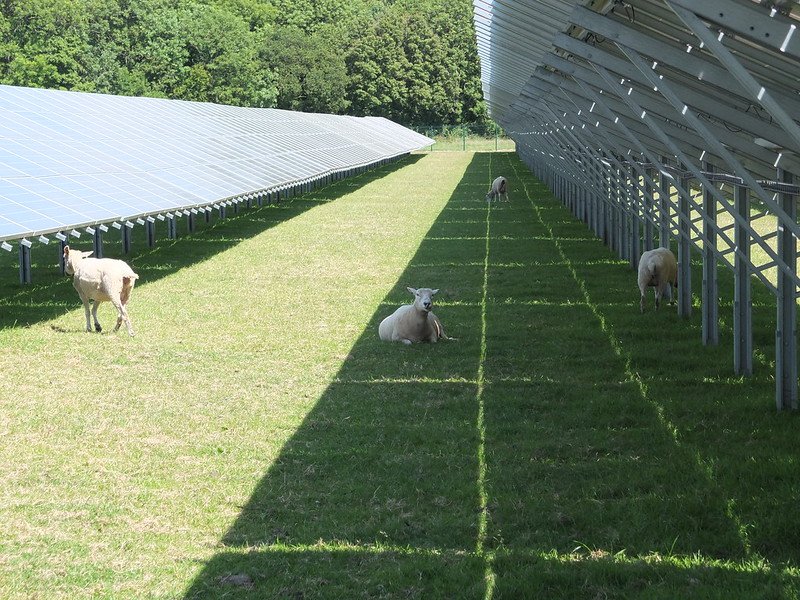

Solar farms with plants can also become fodder for “solar grazers,” like at the Nexamp community solar project in Newfield, New York, where about 150 sheep are “deployed” to prevent plants from growing tall and interfering with the solar panels. Fencing keeps predators out, while the panels themselves shelter the sheep from sun and storms.

Solar companies will sometimes enter into agreements with local farmers to allow sheep herds to graze the vegetation around the solar panels, providing another income stream for the farmer who is leasing the land to the solar farm. Such natural grazing also encourages grass regrowth, increases manure nutrients to the soil, and avoids the costs and pollution of mowing. And the very act of taking plots of farmland out of production for the typical 20 to 30 year lifespan of a solar project rejuvenates top soil degraded by annual cropping and chemical applications.

Meanwhile, new approaches are promising to expand the species of plants that can be grown at solar sites. The U.S. Department of Energy is experimenting with “agrivoltaics” — for example, raising solar panels higher off the ground to enable food crops to be grown in the shade underneath. In the summer heat of a place like Arizona, peppers and tomatoes can be shaded from the scorching sun by the panels, which then retain heat and boost the crops’ growth during the cooler evenings.

Moving forward, solar farms could play a role in food security, as well. With big utility-scale solar farms alone predicted to cover almost two million acres of land in the U.S. by 2030, a huge opportunity is on the horizon to support pollinators, improve soil health, nurture biodiversity, produce food and, not least, slash emissions, all at the same time.