At the time of this writing, the homepage of the Daily Mail, the U.K.’s most widely read news outlet, offers this headline to summarize the prime minister’s March 12 national address: “BORIS: MANY WILL DIE.”

The headline is factually accurate — as the COVID-19 coronavirus spirals across the globe, it is indeed causing fatalities. But in another sense, it is inaccurate, in that it frames the story from an angle that serves the paper’s needs, not the reader’s, by eliciting an emotional response rather attempting to fully describe what is going on.

There can be no doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic presents massive medical, social and economic challenges, and that the press has a duty to report on these. Doing so helps us understand the scale of the problem and hold individuals, organizations and governments accountable for their actions. An example of this is the media’s coverage of the U.S.’s failure to widely test for the virus — a failure that many news outlets have chronicled in cities and towns across the country.

But there is something journalists forget: How we report on challenges affects how likely they are to be solved. News does not simply reflect reality as it unfolds; it plays an active role in shaping it.

This was the medical profession’s assessment of the news coverage of the 2014 Ebola outbreak. During that event, the news cycle fixated on the thousands of deaths sweeping Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone. To be sure, the death toll was pertinent and the lethality of the virus significant. Equally newsworthy, however, was an important story going on right next door that went nearly untold.

In the nearby countries of Mali, Senegal and Nigeria, a highly effective response to the virus had managed to contain its spread to fewer than 30 cases collectively. When the first case was confirmed in the Senagalese capital of Dakar, the authorities were immediately alerted, and then identified and monitored 74 of the patients’ closest contacts. They promptly tested all suspected cases, increased surveillance at entrance points and invested heavily in public awareness campaigns.

Forty-nine days after the country’s first and only confirmed case, Sengalese officials announced they had stopped the virus. The U.N called Senegal’s response a “good example” of what to do when an imported virus crosses borders.

It was an extremely valuable story. Yet many news organizations defaulted to their negative tone, running a variation of the same headline — “First Ebola Case in Senegal Confirmed” — while littering their stories with statistics of the neighboring countries’ fatality rates. Far fewer organizations reported that Senegal’s first Ebola case was also its last, even though doing so not only would have painted a more accurate picture of the situation, it could have communicated lessons drawn from how these countries had contained it — lessons other countries could learn from.

Stories like these were why, in an analysis published one year into the Ebola epidemic, the World Health Organization included “intense media coverage” in its list of factors that exacerbated the crisis. An article in the Lancet also warned of the risks of sensationalizing the outbreak. “Some sources have shared accurate guidance aimed at those most in need, such as… the BBC’s WhatsApp Ebola service,” wrote the author. “But, overall, the media has tended to encourage substantial misunderstanding about the risks of exposure and where the real threat and causes of Ebola lie.”

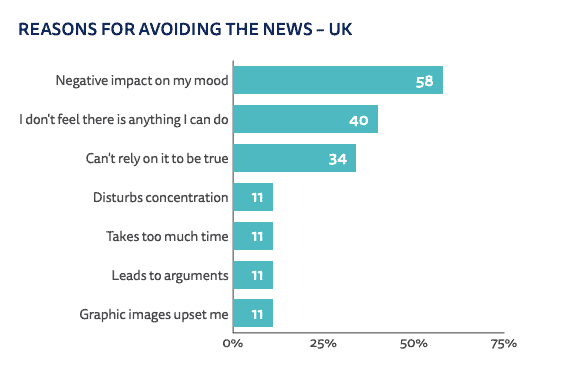

What’s more, relentless scare-mongering isn’t even the best way to get ratings or clicks. The sensational negative reporting practiced by many in the media may be an effective way of initially grabbing our attention, but the “if it bleeds, it leads” news strategy eventually becomes ineffective because negative news is the single biggest factor in audience disengagement.

Instead, I would argue that what we need is “constructive journalism,” a term used to describe news that provides both context and perspective, as well as solutions, when presenting the problem. Despite its reputation, solutions journalism is not to be confused with fluffy, feel-good stories; as I define it in my book, You Are What You Read, it is “rigorous journalism that reports critically on tangible progress being made in order for us to understand how issues are being dealt with.”

There are some news organizations doing this. They are investigating what measures to contain the coronavirus are working, and why they’re working, so that we can learn how best to replicate those efforts. As news consumers, we can actively seek out these stories to mindfully protect ourselves from the overwhelming negative news coverage. (If you are unsure where to access these resources, there is a starter kit available on my website.)

When we learn about solutions alongside problems, it improves our mood, increases our engagement and optimism, and makes us feel more empowered. And there is reason to feel empowered during this crisis — the threat we face can be detected and, if managed well, slowed down and even contained. As individuals, we can minimize the risk to ourselves and others by taking basic precautions. Most of the reported cases are mild enough to recover from without hospitalization. Meanwhile, scientists are cooperating globally, and vaccine prototypes with antiviral trials are being developed.

The quality of our information will be a factor in determining the quality of our response. So, as journalists, let’s make sure we’re telling the whole story.