In Zanzibar, where in some areas 40 percent of the population once suffered from malaria, infections have fallen by at least 94 percent since 2003. They’re not the only ones to have shown incredible success—Mozambique, Rwanda and Bhutan are doing it, too. Paraguay is malaria free! How are they doing this? Is there a model they’re using that can be replicated by other countries?

Malaria is serious

In his book The Mosquito, Timothy Winegard notes that mosquito-borne diseases have accounted for half of all deaths in human history… 52 billion over 200,000 years. (To be clear, some of those deaths were caused by dengue and yellow fever, which are carried by mosquitoes, too.) To this day, malaria is one of the biggest threats to life. An estimated 435,000 people died of it in 2017.

But it seems in some places, at least, we’re winning this “war.” In Zanzibar, they’re combining standard mitigation measures—nets and spraying—with innovative community engagement techniques. Too often, ambitious health programs are unsuccessful because of poor local uptake, but Zanzibar has focused on making sure that everyone is part of the fight, right down to the last villager.

Bottom up

By encouraging communities to be part of the solution, Zanzibar’s government has given individuals a sense of agency and participation, which seems to have been key to the effort’s success. They’ve combined this engagement with mobile technology that connects far-flung villages to health services, and allows officials to more efficiently target their eradication efforts.

In Zanzibar, locals report outbreaks by texting or using a phone app, and health officials respond quickly, allowing them to focus their finite resources on the hot spots. These interventions are free, which makes it easier for communities to get involved. The government has even started using drones to find stagnant water, where mosquitoes breed. As a result of these efforts, Zanzibar hopes to eliminate malaria completely by 2023.

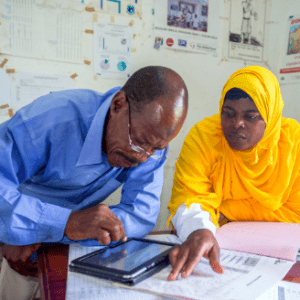

Women are central to this goal. It is often women workers who receive the alert when a community identifies a malaria outbreak and enters it into the Coconut Surveillance app, an open-source mobile reporting application designed by malaria experts. Women’s involvement reflects a worldwide reality—even in the U.S., 80 percent of health care workers are women. In places like Zanzibar, women are home-based community leaders, and in the malaria fight, they can earn a tiny bit of compensation gathering critical information and responding to outbreaks.

This sometimes means traveling by motorbike to affected areas, administering tests for the disease (the testing kits are simple to use and the results are instant), and reporting their findings on their smartphone or tablet.

Reports are passed to the Tanzania Vector Control Scale-up Project (TVCSP) and the Zanzibar Malaria Elimination Program (ZAMEP), which target the area with free nets and spraying within 48 hours.

Early intervention stops the spread of the disease.

This works for a few reasons. The community is involved, women are taking charge, targeting outbreaks is efficient, and the testing, treatment, spraying and nets are all free.

Rwanda

Women are at the forefront of this fight in Rwanda, too, where there were 430,000 fewer malaria cases in 2017 than the year before. This is due to efforts like those in Rwanda’s Mahama refugee camp, home to most of the 61,000 refugees who have fled political violence in Burundi. Burundi has seen an uptick in malaria cases, so women in the Rwandan camp have led the effort to prevent the disease from spreading there from their home country. They do this by monitoring the health of their neighbors, accompanying sick ones to the clinic and spreading the word about Rwanda’s anti-malaria strategy, which consists mainly of nets and spraying houses with insecticide that lasts for up to a year.

“In Burundi, women were not highly considered for leadership, because even the culture was prohibitive for women to become leaders,” Mukamusha Beatriceone, a woman at the camp, told the Telegraph. “Their [women’s] voices are still hidden. So when we become leaders, we are the ones who will raise voices of women in the community.”

Some 52 percent of the deaths that occurred in the Mahama camp used to be caused by malaria, and now that’s down to 0.5 percent. Wow.

Mozambique

In parts of Mozambique, Goodbye Malaria, an initiative run by African entrepreneurs, has found success with a similar mobile reporting technique to the one used in Zanzibar. The team organizes soccer games and art classes to educate families about the disease, and uses a data dashboard and geolocation to track infections and monitor treatments. As with Zanzibar, the group also engages local communities and adapts to the needs and cultural mores of each area. It’s not one size fits all—the process needs to conform to local contexts.

In the areas where Goodbye Malaria—or Tchau Tchau, Malaria, as it is known in Mozambique—has worked, the number of malaria cases has dropped by up to 89 percent.

Isolation vs. Cooperation

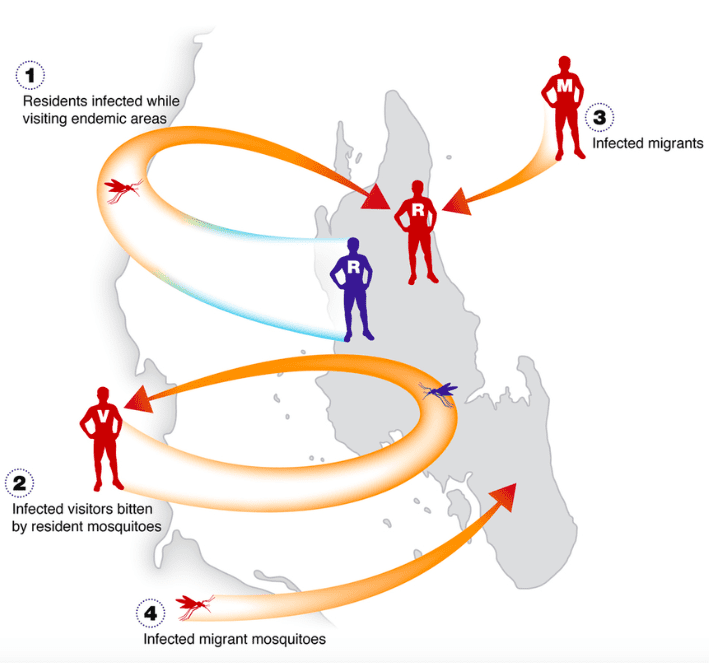

Zanzibar is a semi-autonomous island archipelago off the coast of Tanzania. The fact that it is an island is important, as many countries that fight off malaria find that it seeps back in when workers and visitors from neighboring countries cross the border.

This happens even in Zanzibar. But by and large, being an island has worked in its favor, which makes replicating Zanzibar’s success complicated, since most places are defined by shared borders.

The tiny mountain country of Bhutan is winning the fight. In 1994, it recorded 40,000 cases of Malaria—by 2018, there were just 54. Most of these few cases were day laborers and visitors coming in from neighboring India. (Significantly, in 2017 the only person who died of the disease was a soldier stationed near the Indian border.) An infected Indian worker in Bhutan is required by law to get treatment in a hospital for a few days, but many leave as a hospital stay means lost wages. It’s hard to blame them.

The cases of Zanzibar and Bhutan show that malaria reduction can be achieved, but it requires nations to cooperate and work together if they are not islands or otherwise isolated.

Another sticky issue is that Bhutan is a Buddhist country, so strict religious adherents resist killing other lifeforms, even mosquitoes.

The officials spraying buildings with insecticide had to reframe this practice. Rinzin Namgay, Bhutan’s first entomologist, laughs when he remembers that they would tell anxious homeowners: “We’re just spraying the house. If a mosquito wants to commit suicide by coming in, let it.”

Bhutan’s relatively small size has helped it, too. In a giant country like India, where culture and politics vary widely from region to region, it’s harder to make a widespread eradication program work. But even in India, the number of malaria cases is down.

Completely free

Many of the earliest countries to eradicate malaria are island nations: Saint Lucia (1962), Taiwan (1965), Dominica and Jamaica (1966) and Cyprus (1967). Paraguay, in South America, was declared completely free of malaria in 2018…the first South American country in 45 years. In the past 12 months, the World Health Organization also certified Algeria, Argentina and Uzbekistan as malaria-free.

Regions of Africa and elsewhere have seen resurgences of the disease, however. Some mosquitoes have developed resistance to the sprays, and in places, the microbe is mutating. So the fight goes on. But targeting and engaging the help of local communities seems to be a technique that is working. Though nets and indoor spraying are not new, engagement at the local level has increased dramatically. Early detection of outbreaks and quick (free) responses has made a difference—a huge difference.