Twice a week, Amy Yang drives her white Chevy Malibu to Mollie Wagar’s apartment in a senior living community in Fort Worth, Texas. Wagar, 78, lives alone and is a bit of a night owl, so Yang always calls her a few minutes before her scheduled 9 a.m. arrival to warn her she’s on the way.

Once situated in Wagar’s living room, an array of devices appear from Yang’s black cargo pants and medical bag—a stethoscope, a blood pressure cuff, a blood sugar meter. While the paramedic gets to work, she chats with Wagar about her recent road trip to Mississippi and new developments in her health since they last saw each other four days earlier.

These casual visits and friendly chats are a gratifying change for Yang, who, until about a year ago, spent 11 years speeding patients to emergency rooms in an ambulance. Now, she is able to develop a slow-paced relationship with patients like Wagar, witnessing and monitoring their health improvements first-hand. Wagar’s situation isn’t an emergency, but in another city it might be treated as one, not because she requires urgent care, but because most cities don’t have a system like Fort Worth’s.

In most cities, a call placed to 911 triggers an automatic series of responses involving an ambulance, a crew of paramedics and a rush to the ER, sirens blaring. But this response is often excessive—one in three 911 calls don’t require an ER visit. Yet few cities have a system in place to deal with cases like Wagar’s—non-emergencies that nonetheless necessitate a medical professional to be dispatched to the person’s home.

For a long time, Wagar, who has diabetes and stomach problems, often called 911 for help. These calls would inevitably land her in the hospital, where she’d receive a full, costly workup, often after her health problems had escalated. It was during one of these stays that she first met Yang, who connected her with the MedStar Mobile Integrated Health Program, one of the U.S.’s first community paramedicine programs.

Launched in 2009, MedStar’s idea was simple: empower paramedics to provide care beyond simply transporting people to emergency rooms. Giving paramedics more time and flexibility to customize their responses to non-emergency situations, the theory went, would provide more effective care for patients, save money for cities and depressurize overburdened ERs.

Community paramedicine programs emerged in rural Canada in the late 1990s to serve populations where medical needs were high, but doctors few and far between. The concept was described in a U.S. publication in 1996 as a way to “decrease emergency department utilization, save health care dollars and improve patient outcomes.” Fort Worth became an early adopter after discovering that it had a small population of residents who disproportionately used 911 when they needed non-emergency care. Today, community paramedicine programs are being developed in countries around the world, from the United Kingdom to Australia to the Maldives.

The concept sounds straightforward. After all, who better to address the root causes of ER visits than the paramedics who interact face-to-face with patients in their own homes? But there are complexities. Implementing the community paramedicine model requires a radical shift in how an entire sector of the medical system views its job. “Our goal is to not be the patients’ medical home or their primary provider,” says Desiree Partain, MedStar’s Mobile Integrated Healthcare Manager. “Our goal is to determine what their gaps are and then to link them to resources in the community.”

Wagar’s case is a prime example. After she was flagged as a high-utilizer of 911 this summer, Yang visited her at the hospital to explain the mobile health care program. Wagar agreed to give it a try. Now, for 30 days, per Wagar’s insurance authorization, Yang is visiting Wagar at home twice a week to check her vitals and help manage her prescribed treatment.

Since Yang’s visits began, Wagar hasn’t been back to the hospital. “I’ll be quite frank,” says Wagar. “MedStar seems to be better than the home health care people when they come in. They take a little more time, a little more personal interest. [Amy] really cares, and I feel like she’s a friend and not just someone who’s doing her job.”

That job goes beyond rote medical treatment. Yang helps patients navigate America’s convoluted health care system, coordinating care between a patient’s doctors and explaining diagnoses and prescription regimes. She often calls doctors’ offices on her patients’ behalf to clarify instructions or address new health issues. Yang will even sometimes attend doctors’ appointments alongside her patients.

Other work Yang undertakes has seemingly little to do with her medical training. Many of her patients’ problems stem from social and environmental issues that a 15-minute doctor’s appointment might not uncover. Is a patient skipping his follow-up appointments? Yang can observe that he lacks transportation and organize a ride for him. Is a diabetic not eating correctly to manage her illness? As a visitor to her home, Yang can observe that she is living in a food desert, and direct her to a nearby food pantry with quality groceries, or help her apply to Meals on Wheels. Or maybe it becomes clear to Yang that a patient is unable to carry out basic tasks. She can set them up with home health care services, or, if the problem is psychological, connect them to mental health resources.

“I think what the health care industry needs to understand is the role we play is truly being other organizations’ eyes and ears,” says Partain. “We’re going into these patients’ homes where the hospitals and some other agencies don’t have that advantage.”

Saving money, and needing more

According to Partain, out of over 20,000 EMS providers in the U.S., only around 300 have community paramedicine programs. Each is shaped to serve the needs of its specific community. In Fort Worth, for instance, with a metro-area population of 7.5 million, congestive heart failure and high-utilizers of ERs were the most pressing issues. In rural Eagle County, Colorado, on the other hand, the problem was simpler: basic access to care. As Chris Montera, CEO of the Eagle County Paramedic Services (ECPS) quips, Eagle County is a “tale of two stories.”

Spread across a vast expanse of some of the world’s most breathtaking natural terrain, Eagle County’s economy is fractured, with a high-wealth population clustered around the Vail and Beaver Creek ski resorts, and on the valley floor in the shadow of the mountains, communities of lower-income resort workers and service providers, many of whom lack access to health care.

In 2009, ECPS started one of the first rural community paramedic programs in the U.S. At the time, the county’s uninsured rate was extremely high, and Montera determined that the new program could increase access to primary and preventative care. As the program has expanded, they have added additional services like a long-term, in-home detox program (their six-month sobriety rate is higher than typical, around 50 percent, says Montera) and a joint initiative with a team of mental health clinicians to respond to suicide calls. According to Montera, Eagle County suffers from a suicide rate that is three times the national average, but in the year that their program has been in place, they have “reduced ambulance transfer off-scene by 78 percent.”

By providing more customized care and addressing the underlying elements of patients’ health problems, Fort Worth and Eagle County are saving money as well as lives. In 2008, the year before MedStar launched its Mobile Integrated Healthcare Program, 21 patients were taken to local emergency rooms by ambulance 2,000 times, racking up $962,429 in transportation charges alone. By contrast, an analysis of 670 patients enrolled in the program from 2013 to 2018 determined that a total of 5,116 ambulance trips were avoided during that time, with a total savings of $2,143,604. Between the ambulance, ER and hospital admissions that were prevented, $24,922 per enrolled patient was saved in Fort Worth.

As for Eagle County, Montera says that in the first four years of the ECPS program, “We were consistently seeing right around $5,200 of health care savings per individual.”

But demonstrating the value of community paramedicine programs is only half of the equation. The expansion of the model requires a paradigm shift in how EMS programs make money. Historically, EMS services in the U.S. have been paid for their transportation services. A person calls 911, an ambulance arrives, paramedics provide critical care and the patient is delivered to a hospital, accruing hefty bills along the way. The idea behind community paramedicine is to provide lower-impact care that reduces costs. That requires a whole host of stakeholders—from hospitals and specialty clinics to insurance companies and tax payers—to buy into the system.

“The way ambulance services in the U.S. and most places, for that matter, have been reimbursed is to transfer patients to hospital,” says Dr. Peter O’Meara, an internationally recognized Australian expert on community paramedicine. “That’s how it’s been done historically. And that’s not a great model, because obviously the benefit is not taking people to hospital. So you have to find someone who’s willing to pay to not take people.”

Fort Worth is moving towards a capitated financial model, where hospitals, home health providers and other referring institutions pay a set fee per patient enrolled in the program. Some patients like Wagar are authorized for 30- or 90-day programs covered by their insurance. MedStar also supplements their Mobile Integrated Health Program with revenue from specialty care transfers. But if the 911 team flags a high-utilizer patient who isn’t covered by one of the above entities, MedStar often picks up the tab.

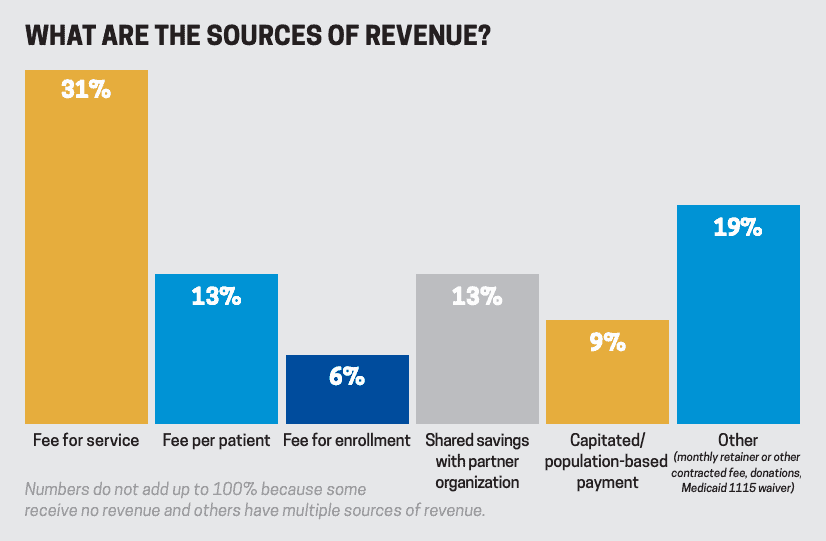

Ten years after its program began, Eagle County is just beginning to sign on health insurance companies. The program has stayed afloat so far mainly through grants and state funding. But many other programs are on shakier financial footing. A 2018 survey by the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians found that, of the 129 programs included in the study, only 36 percent agreed or strongly agreed that their programs were financially sustainable. A quarter of the respondents said their programs were not.

Smarter care requires higher skills

Just as important as program funding is the issue of paramedic education. The U.S. lags behind other countries in the standards paramedics must meet to perform their jobs. With increased education comes the ability to provide greater medical care, but efforts to upskill paramedics have faced some surprising opposition. For instance, some nursing unions view more highly skilled paramedics as a threat to their own jobs. Other stakeholders feel it is simply an unnecessary requirement.

“The U.S really needs to deal with their education level for entry-level paramedics before they can really attain the practitioner-level-type community paramedic,” says O’Meara. The issue is being addressed on a state-by-state basis. Montera has been advocating for changes in Colorado, which recently passed a law to recognize paramedic degree programs, and where the state college system will soon begin offering programs in paramedicine. Oregon now requires an associate degree for the position, and North Carolina has submitted a proposal to follow suit by 2023. “The true paradigm shift we need to make in the United States is really around education and how we view paramedics,” says Montera.

That image of paramedics as ambulance-driving crisis managers, so ingrained in our minds, may be the biggest hurdle. As with any new model of medicine, it takes trial and error to get things right. Both MedStar and ECPS are committed to transparency, hoping an open-source standard will help other programs learn from their successes and failures.

“Health care has been changing and evolving from quantity to quality, and we see ourselves as a provider of health care services,” Partain says, adding that EMS programs trying innovative approaches need to be willing “to plan it a little bit, but [then] we’re going to throw ourselves out there. We’re going to bleed, we’re going to bruise, we’re going to make mistakes, but we learn best from our mistakes. And that’s just what we’ve done.”