On the drizzly first Tuesday in March, voters crammed into a historic white clapboard meeting house on a hill in Stockbridge, Vermont. It was Town Meeting Day, when Vermonters across the state gather to debate and vote on local government. And the election for the next member of Stockbridge’s three-person select board, the main governing body of this town of just over 700 people, had drawn record turnout.

As voters waited to cast handwritten ballots in a long queue that snaked around wooden benches, University of Vermont sophomore Sarah Andrews approached locals, notebook in hand. Andrews and two classmates were not just there for course work: They were there as part of UVM’s Community News Service, reporting for the White River Valley Herald, the weekly newspaper that covers 16 towns in this rural region.

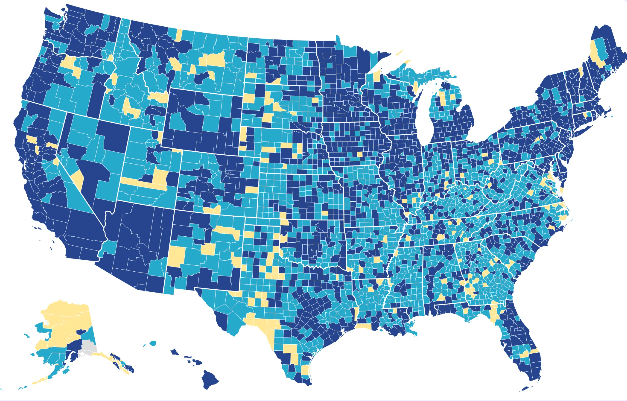

Small newspapers like the Herald have long been the main way of recording and distributing information about community happenings. But local news outlets are disappearing. The 2023 State of Local News report found that about half of all counties across the country have only one local news outlet, and more than 200 counties have none.

As local news deserts grow, universities are stepping in. With initiatives ranging from student-staffed statehouse bureaus to newspapers run by journalism schools, these academic-media partnerships are bolstering local news.

“It’s a short-term win and it’s a long-term win,” says Penny Muse Abernathy, a visiting professor at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, and co-author of the local news report.

University-media partnerships provide reliable local news coverage in communities where it is needed. In the process, students get hands-on experience with community decision-making in a way that shapes their careers and worldviews going forward.

“Too often over the last 20 years, we’ve tended to focus on teaching students what we assume are professional digital skills for the digital age, when in fact journalism at its core teaches not only the journalist but the citizen how to employ critical thinking and make wise decisions,” says Abernathy.

Closures of smaller news outlets over the last several decades have left many regions without reliable media coverage. Since 2005, the number of newspapers in the US has dropped by a third, and the number of journalists has declined by 60 percent. The erosion of local news makes it harder for community members to be aware of the issues in their regions.

“Most of the decisions that affect our immediate everyday life occur at the local level,” says Abernathy.

Through university-led journalism programs, students — under the tutelage and editorial supervision of faculty members — are stepping in to fill in some of those gaps. The model isn’t new: The University of Missouri has been practicing a “teaching hospital” approach that involves students in community news coverage since 1908. Now, in the current media landscape, higher education institutions are looking at how they can both offer students enriching experiences and contribute to communities, according to Richard Watts, who heads the University of Vermont’s Center for Community News.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

“Students like to do things that are real,” he says. “There’s a sense of agency about writing real stories that real people read and make a real difference.”

There are about 120 such programs at colleges and universities across the country, according to Watts. The Center for Community News found in 2023 that over the last year, more than 2,000 student journalists across the US had produced more than 10,000 news stories that were published in community outlets. The stories were estimated to reach more than 14 million people.

Often offered to students in the forms of classes, the programs require a high level of commitment from faculty members — editing stories for publication is more intensive than typical grading. Across different regions, the scope and focus of programs varies, says Watts.

Louisiana State University’s Manship School of Mass Communication has taken advantage of its location a few miles away from the State Capitol to bolster coverage of the legislature.

News coverage of state policy-making is among the casualties of the erosion of local news. Across the country, the number of reporters covering statehouses full-time declined by 34 percent between 2014 and 2022.

As press coverage of the Louisiana legislature diminished, LSU launched a statehouse bureau in 2016. Through a high-level journalism class, student reporters cover committee meetings and floor proceedings. Grant funding allows the program to keep students on as interns to cover the weeks of the legislative session after the semester ends. Christopher Drew, a former New York Times investigative reporter and editor who heads the bureau program, edits the stories. Then they’re made available for any news outlet to publish for free.

Ninety-five outlets have run LSU student statehouse stories, ranging from some of the state’s largest newspapers to small weekly and bi-weekly papers, many of which Drew says wouldn’t have another option to get stories about news from the statehouse.“Our students never have any problem getting taken seriously by lawmakers because we often are the hometown reporter for the lawmakers,” says Drew. “A lot of them come from places [where] the only thing that constituents could read about what they do comes from what the LSU students do.”

The idea is spreading; 20 states have some form of university-led statehouse bureau, and Drew is involved in conversations with schools interested in launching programs in additional states. LSU also offers an investigative journalism course, focused on civil rights era cold cases, which similarly distributes stories to outlets. Drew is working on a new project that would create a network of universities and colleges around Louisiana, partnering journalism programs with small local news outlets.

LSU senior Claire Sullivan is taking the statehouse course for the second time this spring. She sees the community news model as mutually beneficial for students like herself who want experience and local news outlets that want coverage.

“It’s the best kind of motivator,” says Sullivan. “You want to do your best job for the local outlets.”

The Oglethorpe Echo has been covering the issues of Oglethorpe County in northeastern Georgia since 1874. The weekly was poised to shut down in 2021, when the long-time publisher was ready to retire. Instead, a community member hatched a plan for the local paper to be taken over by the University of Georgia’s Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication.

Over the last two and a half years, students have reported the stories that fill the Echo’s pages. During fall and spring semesters, the newspaper is staffed by students in a senior capstone class. Over summer and winter breaks, students are hired as interns, so there’s no break in news coverage. The paper was converted to a nonprofit, and Andy Johnston, a longtime sports journalist who had been an adjunct professor, came on as the paper’s editor.

Student journalists have dug into issues related to limited rural broadband access, and use of a particular form of fertilizer on local farms. In its first full year of operating under the university, the paper won nine awards from the Georgia Press Association.

One difference between university-led media and traditional local outlets is that student reporters turn over frequently, so they don’t have the long-term knowledge and relationships that a professional reporter would. But editors — both employed by universities and with community news outlets — help provide that expertise. In Vermont, when the White River Valley Herald picks up stories written by UVM students, editor Tim Calabro says he occasionally adds in local context that students don’t know.

When the University of Georgia took over the Echo, Johnston says there was an adjustment period of building trust with the community. The university is located about 25 miles west of Oglethorpe County, so students don’t live locally. But the feedback he gets is generally positive. Readers appreciate having a local news source, and they particularly like slice-of-life stories that feature their friends and family members.

“We’re writing to tell the stories of the community, tell the stories of the county,” he says.

Back in Vermont, on Town Meeting Day, a total of 139 people voted in the election for Stockbridge’s new select board member. Two days later, Andrews’ story about the election ran in the White River Valley Herald.

For the Herald’s editor, Tim Calabro, UVM students’ stories helped his limited staff cover news around the region on the biggest single day for local government of the year. But Calabro says there are broader benefits of the program beyond filling the paper with news.

“Of all the dangers that newspapers, news organizations of any stripe are facing, the biggest worry is that people just won’t care about what’s going on in their communities,” Calabro says.

Not every student who goes through a university-led news program will go on to a career in journalism, he says. But even for those without ambitions in journalism, he sees this kind of program as valuable for engaging young people in communities: “Being a human being in society,” as Calabro puts it, “it’s good to care about society.”