By 6 a.m. on a steamy Friday morning in August, a handful of food carts and two produce stands are already set up and serving commuters on their way to the elevated 7-train subway stop above Corona Plaza, at 103rd Street and Roosevelt Avenue in Queens, New York. The plaza is named for the neighborhood around it, and while it may seem untimely now, maybe someday the name will also symbolize the dawn of a new era in New York City’s tortured relationship with street vendors.

Gabriela Almaraz was one of many New Yorkers who turned to street vending when the coronavirus pandemic shuttered the economy last year. She’s lived in or near Corona for the past 25 years, and previously worked as a housecleaner. Now she makes and sells tacos, quesadillas and other Mexican staple meals — just as she did as a child with her mother on the streets of Mexico City.

Currently, for a city of 8.8 million people, there are only 5,100 permits for mobile food vendors and 853 general merchandise street vendor permits available. Waiting lists are in the thousands, and the city hasn’t accepted new applicants for years. Only veterans or their surviving spouses can get new street vendor permits.

The city only charges $200 every two years for mobile food vendor permits and $100-$200 a year for general street vendor permits. But the arbitrary cap fuels a black market for those who have them to illegally lease them out. The going rate to rent an NYC mobile food vendor permit is between $20,000 and $30,000 for a two-year period.

Despite the cap of around 6,000 permits overall, there are an estimated 20,000 street vendors across New York City, according to the Street Vendor Project, a citywide association of street vendors.

It’s technically a $1,000 fine for unpermitted vending, but last June, the city administratively removed NYPD from enforcement of street vendor regulations, partly in response to last year’s protests against police. At the time, without a clear alternative for enforcement in place, the change effectively suspended street vending regulations in the city. Many saw an opportunity that wasn’t there before.

Before the pandemic, Corona Plaza had around 30 established vendors, but by the fall of last year, their numbers swelled to more than 100, selling food as well as household items, baseball caps, sneakers, clothing and flags of every Latin American country. Some were new vendors, some moved to the plaza from other parts of the city that lost foot traffic because of the pandemic. But most Corona Plaza street vendors still do not have a permit to sell food or other goods curbside. As vibrant as the plaza is today, the city could wipe it out at any moment, and many are anxious that it might, as officials transition this year to a new system for enforcing street vending regulations.

“We don’t have permits or licenses, but we know the risks we are taking,” says Almaraz. “A lot of us who are vendors here were vendors in our home countries. What we’re trying to do here is, until we’re able to get those permits and licenses, we’re organizing to keep the plaza clean so that we’re not drawing negative attention from enforcement agents.”

Just before 7 a.m., a large maroon and white truck pulls into the center of the plaza, and workers begin unloading and setting up tables, canopies and goods for another large produce stand. It’s one of four vendors with the weekly NYC Greenmarket, one of 132 city-recognized farmers’ markets around New York. The Greenmarket program works with local farmers, and it allows shoppers to buy produce from its farmers using SNAP. This Greenmarket site has been here since 2007, before the city even built Corona Plaza, but after street vendors first lined these sidewalks. Now, everyone feeds off each other’s success.

“It’s a busy market,” says Michael Hurwitz, director of food access and agriculture at Grow NYC, the nonprofit that runs the Greenmarket program. “It’s interesting because there’s some overlap in product between the [Greenmarket and non-Greenmarket] producers but everyone builds their own relationships and their own committed customer base.”

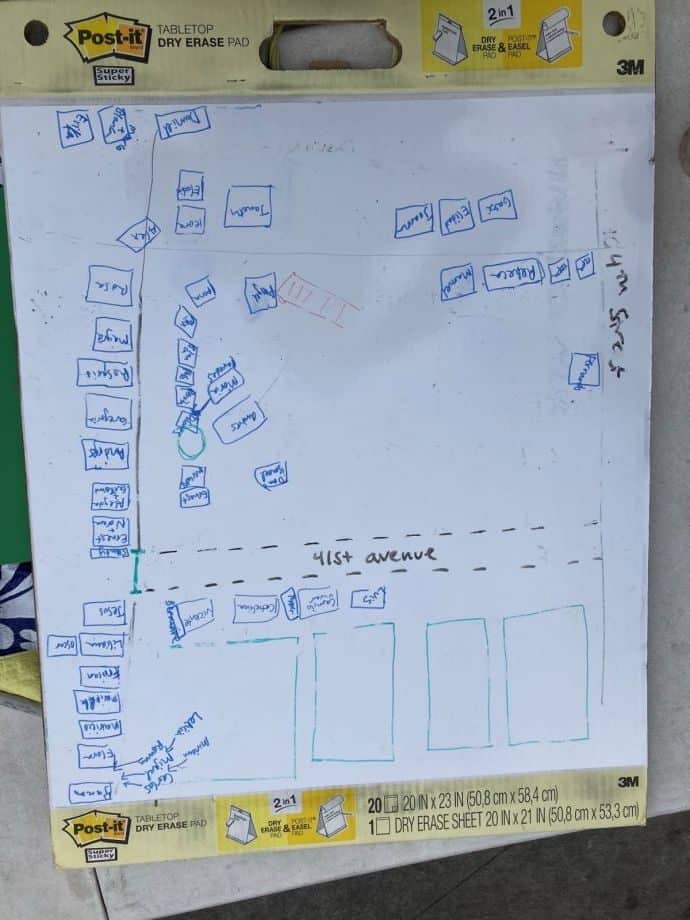

When the numbers of Corona Plaza street vendors swelled last fall, it initially caused some chaos because new vendors would set up in established vendors’ spots, or in the area where the Greenmarket farmers set up on Fridays. But, with some help from the Street Vendor Project, the Corona Plaza street vendors organized themselves. They established a community agreement with rules around managing trash, and made a map of the plaza with designated spots for each vendor and for the Greenmarket on Fridays. They elected representatives for six-month terms to resolve disputes, facilitate monthly vendor meetings and coordinate with other groups such as the Greenmarket program. They didn’t establish a nonprofit or other formal entity, but there is a WhatsApp group.

“Nobody steps on anybody’s toes,” says Mohammed Attia, director of the Street Vendor Project and a former street vendor himself. “Everybody’s happy, everybody’s doing business, everybody’s supporting each other. It’s such a great example of what the city could look like. Hopefully one day we could scale this up.”

An urban fixture for generations

New York City’s love-hate relationship with street vending goes back a long way.

The city created a Department of Markets in 1917 to operate and supervise the city’s wholesale markets for meat, fish and produce. The department eventually took the lead role in the city’s goal to eliminate what it called “open-air markets.” As of 1929, when the city’s population was just under seven million, the city officially counted 6,053 “pushcarts” across 57 open-air markets, according to a Drexel University history of open-air markets in New York City from 1929 to 1948. These “peddlers” sold a reported 50 million dollars’ worth of food annually to 1.5 million people.

According to the Drexel University history, city officials believed open-air markets to be unsanitary, a traffic hazard, a fire hazard and “a relic of the past that is no longer necessary.”

But even back then city officials were aware that street vendors can make business better for everyone, including brick-and-mortar businesses. As one of the Department of Markets’ own annual reports stated, “It is a fact that where these open-air markets are operating, rents and property values have increased and in many instances where pushcarts are allowed on only one side of a street, the storekeepers on the other side have requested that pushcarts be permitted for part of the day to stand on their side of the street to attract business to them.”

During the Great Depression era, the economic importance of street vending was not lost upon city officials. As a 1937 annual report from the Department of Markets stated, “Peddlers are a means of distributing great volumes of food tonnage at low prices to the poorer sections of the city, and since further thousands of families do depend on this method of retailing for a livelihood, it was the plan of the mayor to place the peddlers in sanitary enclosed markets, instead of the public street.”

So rather than eliminate street vendors, the city came to settle on a policy of building enclosed public markets for them — though the enclosed markets never had enough room to fit all the vendors working in the open-air markets that they were built to replace.

It nearly worked. By 1942, the city counted just 362 street vendors remaining across 10 open-air markets.

In 1969, NYC’s Department of Markets merged with the city’s Department of Licensing to form the Department of Consumer Affairs. The agency’s mission has continued to expand, and today it’s known as the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection. But the same types of resistance to street vendors still play out today.

“Usually folks who put down street vending really have arguments of aesthetics,” says NY State Senator Jessica Ramos, whose district includes Corona Plaza.

Ramos, who says she is the granddaughter of a street vendor in Colombia, has been leading the charge for a bill that would forbid municipalities in the state from placing any caps on street vendor permits.

“For me, it’s very hard to justify removing a human being and their livelihood simply because it doesn’t look pretty or their existence bothers a particular person,” says Ramos. “I believe their honest work supersedes anybody’s sense of aesthetics. I have great respect for the woman who wakes up at three o’clock in the morning to make 500 tamales so that she can feed our essential workers for just a little bit of money to keep a roof over her head and to feed her kids. What’s more beautiful than that?”

Progress with licenses, problems with enforcement

NYC’s current cap of 5,100 mobile food vendor permits has been in place since 1983. The city’s population has grown by nearly two million since then. In January of this year city council passed Intro 1116, which put in place a plan to add 400 more mobile food vendor permits every year for ten years, starting in 2022. The law was the result of years of advocacy led by the Street Vendor Project and immigrant rights groups; the vast majority of street vendors are immigrants, including many who have been street vendors for decades.

That in itself would have been a huge victory, but the bill also officially codified into law the earlier administrative changes that took enforcement of street vending regulations out of the hands of the NYPD and into a new civilian office, the Office of Street Vendor Enforcement. The new office goes back to the original home of street vendor regulation, the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection.

But the transition of responsibility for enforcement has been rocky. Despite the new law, the NYPD has still gotten involved in cracking down on street vendors. In May, the developer of Hudson Yards called in the police to kick out vendors from open areas within the grandiose mega-development.

In late June, NYPD officers swept through a bustling section of Fordham Road in the Bronx to eject unlicensed street vendors, more than a year after Mayor Bill De Blasio administratively removed NYPD from street vendor enforcement. Defending the action to a radio program caller, De Blasio said “the mom-and-pop stores that build themselves up over years and really suffer if those rules are not followed.”

At the same time, as DCWP started to send around its own agents to conduct outreach about the new enforcement process, those agents weren’t leaving a good first impression.

At Corona Plaza in mid-June, Attia told me, “A few weeks ago, DCWP agents or inspectors came here and were supposed to do some outreach and education to vendors, and instead they were scaring the vendors, telling them they were going to start enforcing on June 1, and they would kick out every unlicensed vendor. That was problematic. It hasn’t happened yet, but there’s people feeling the threat, hearing the tough language that they’re going to have to go. And that’s not what we want to see.”

Some DCWP agents seem to be learning about street vending regulations on the job — sometimes from street vendors themselves.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.In July, Attia helped resolve an incident where DCWP enforcement agents issued a violation to a street vendor for being in a restricted area that goes from 33rd Street to 42 Street along Eighth Avenue in Manhattan, even though the vendors were further uptown and therefore not inside that restricted area. DCWP tells Next City it started the process of withdrawing that violation.

Less than a week later, Attia got a call from a vendor near Brooklyn Bridge Park. DCWP enforcement agents were attempting to confiscate the street vendor’s license because they said the distance from his cart to the exterior wall of the building at that location was less than 12 feet. However, regulations for mobile vendors clearly state that if the sidewalk itself measures at least 12 feet from the building to the curb — which was the case in this instance — the vendor is allowed to be at that location as long as their cart is right along the curb, which it was. DCWP tells Next City that in that situation, the agents did not issue a violation and returned the license to the vendor.

“We transitioned from NYPD for a reason,” says Attia. “To get rid of that disrespect, that rudeness. We wanted to have a civilian agency that respects people, that supports them. Now DCWP doesn’t seem interested in that, obviously.”

The agency says these incidents are the exception, not the norm. As of July, DCWP had 12 staff members dedicated to street vending inspections and was in the process of hiring and training approximately 12 additional inspectors. DCWP’s enforcement of street vendor regulations officially began on June 1, and by July 16, the agency says its street vending inspectors had conducted 433 inspections and issued 226 violations.

About one in six inspections were in the Times Square area, which reflects the tendency of street vendor complaints to be concentrated in tourist areas. Out of 2,764 complaints DCWP had received about street vendors as of July 16, 1,274 complaints were in tourist-heavy Manhattan, followed by 685 in Brooklyn (the most populous borough), 519 in Queens (the second most populous borough), 203 in the Bronx and 27 in Staten Island.

“Vending is a complicated issue that touches us all — from the vendors themselves to local businesses to residents and visitors,” says a DCWP spokesperson, via email. “Our goal is to strike a balanced approach, which includes ongoing education coupled with scaled, strategic enforcement, especially in problematic areas.”

Self-governing for a better city

At around 9 a.m., another set of workers arrives at Corona Plaza to water the plantings and set up colorful tables and chairs. The plaza today shows what’s possible through a cooperative instead of an adversarial approach to working with street vendors.

“This is the first time it’s really been coordinated like this,” says Hurwitz. “There’s only certain configurations that work for our farmers, just basic things to minimize what farmers have to work out with street vendors at six in the morning when the farmers just drove all the way down to the city. That was appreciated and understood by the Street Vendors Project and the [Corona Plaza street vendor] reps we’ve been working with. It’s a model for city government to ensure that the plazas are activated and activated well, that the folks who are there are working together for the collective whole and it just builds community.”

That the plaza even appears in its present form is a testament to the city working with the community instead of against it. The nearby Queens Museum started in 2005 applying for temporary permits to shut down the small street running across the area for cultural events. It became a wildly popular space. By 2012, the city officially de-mapped the roadway, and finally, in 2017, broke ground on a total redesign of the plaza, part of a citywide program of pedestrian-oriented plaza building initiated under the Bloomberg administration. The reconstruction was completed in 2019.

Mariela Vivar has been a street vendor at Corona Plaza for three years, selling small ceramics and other household goods and gifts imported from Mexico, where she’s from originally. She was one of the vendors who previously organized to strike a deal with the local police precinct — as long as they kept the walkways clear, the local police officers agreed not to bother them.

When the Corona Plaza vendor numbers started surging last fall, she and a few other established vendors started explaining to newcomers where they could set up without taking established vendors’ spots, without blocking the walkways as they had promised the local police precinct, and to keep space clear for the Greenmarket — which only sets up on Fridays.

“Some would move, others wouldn’t,” Vivar says. “Trash was being left out, people were fighting among each other. We started going around to talk to people about the Street Vendor Project, about what was going on. One day I had proposed a meeting and we talked to three or four other longtime vendors and brought everyone together.”

The first vendor meeting took place in January, out in front of a bakery at one end of the plaza, at noon — the warmest part of the day.

“We all came together, introduced ourselves, our names and what we sell,” Vivar says. “We agreed to start meeting as a group. Started getting to know each other. Shared a community agreement.”

The first point of the community agreement was for vendors to take out all of their trash before leaving every evening.

“The vendors know it’s going to come back on them,” says Alamaraz. “The trash always gets blamed on the vendors.”

To help manage waste, Street Vendor Project worked with another organization in the neighborhood to hire two women from the community on a part-time basis to collect trash from vendors and drop it off in a designated spot on the plaza where city sanitation workers can collect it every night.

The second point was to respect everyone’s established spots and to abide by city rules to keep sidewalks safe for pedestrians.

“After we started meeting, people started making their stands a little bit smaller so there was room for more vendors, and to have more space for people to walk through,” Almaraz says.

At the second meeting, two weeks later, Vivar, Almaraz and other vendors signed the agreement. For the next few months, the group met every two weeks. Some of the early meetings were dedicated to mapping out the plaza and designating which spots belonged to whom.

To help maintain order and facilitate communication, they also elected two representatives from their ranks to serve as liaisons with other entities — the police precinct, the Greenmarket Program, or city health officials. During the pandemic, the city began using part of the plaza curbside for a mobile vaccination site that operated out of two tour buses.

Vivar served a term as one of the first set of Corona Plaza vendor reps. More recent meetings have covered things such as the city’s regulations for vendors. Rules are stricter for food vendors, for obvious reasons. Health concerns are real, and one bad vendor risks spoiling the reputation of every food vendor at the plaza. In addition to getting a street vendor permit, which isn’t currently available, food vendors must take a food safety training course and obtain a license from the city’s health department. Fortunately, the city does not limit the number of food handling licenses.

Vivar says they’ve also often talked about best practices for staying safe amid the ongoing pandemic. Corona is a working-class neighborhood filled with essential workers; its COVID-19 caseload was among the highest in the city. Nearby areas were even worse.

The group recently scaled down to monthly meetings. Most recently, they’ve talked about the changes to the city’s street vendor enforcement process, although updates from the city have been scant.

“We have asked a zillion questions — how many people will be there, what languages will they speak, what training will they get,” says Attia. “All these questions are left unanswered.”

The plaza could be cleaner. And it could use more programming, which would require more funding to pay artists. But Corona Plaza doesn’t have generationally wealthy donors funding a lavish park conservancy like those for Central Park, Riverside Park or Prospect Park. It’s up to the city to step in and dedicate more resources to fund public spaces such as this one — a space that serves many essential workers who keep the city going during a pandemic, but who are not paid enough to bring more resources of their own to the table.

But even if city officials did commit more resources for the plaza, there’s no guarantee that they would allow the vendors who are already here to obtain the permits they need to stay.

“Really what I would like to see is for the city to take street vendors seriously and work with them to provide them with the infrastructure and the resources they’ve been lacking,” says Ramos. “There is more that we can do if only we will sit down with them and listen to what they need. Street vending is so integral to who we are as New Yorkers, but it’s ignored and marginalized because it’s immigrants, it’s people of color, it’s undocumented people, it’s veterans.”

This story originally appeared on Next City.