In the past two months, some 420,000 people have left New York City, propelled by the coronavirus to seek out lower-density living situations. Though it’s far too early to predict how the crisis might shift living patterns permanently, both residential and commercial real estate activity in the suburbs of some cities seems to be rising. A survey conducted in April, as the virus was peaking in several U.S. cities, found that 39 percent of urban dwellers would consider moving “out of populated areas.”

While lower-density life allows for more social distancing, the design of many newer suburbs can create a little too much distance, isolating people into large lots and private vehicles. “Right now the single-family subdivision is kind of a hell realm” says Tom Dolan, an architect who designs housing based on a model that some planners call the “missing middle.”

The missing middle refers to a range of housing that splits the difference between urban core and suburban sprawl, with the aim of giving neighbors space without sacrificing community. “The crucial blend of control and conviviality,” as the book Happy City by Charles Montgomery puts it, that allows us to “moderate our interactions with strangers without having to retreat entirely.” It’s a centuries-old model that might be well suited to a new world in which home-based work, non-traditional families and six feet of personal space are the norm.

“Less than family but more than neighbors”

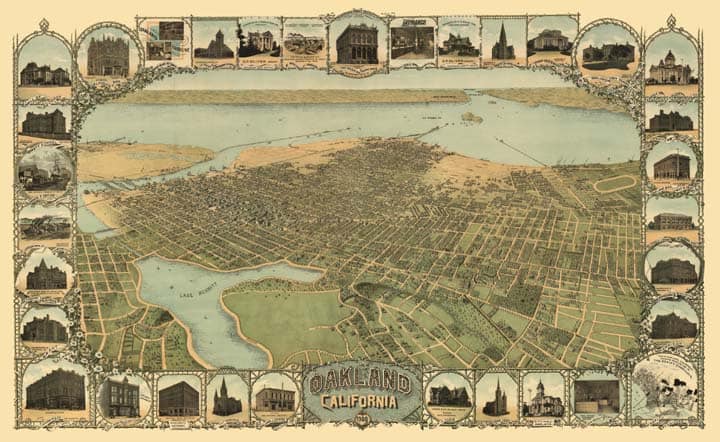

In the late 1800s, an Italian clan called the Salemis built themselves a family compound in Oakland, California. At the time, Oakland was a quiet but growing city with a small-town feel, blanketed with namesake oaks and criss-crossed by a network of streetcars called the Key System.

The Salemi’s small complex there, which architect Dolan describes as “Yankee buildings in a Mediterranean site plan,” consisted of four petite wood-framed homes surrounding a brick courtyard. The property was filled with fig trees and grapevines, from which the Salemi family is rumored to have made wine during Prohibition.

By 1983, however, cars had replaced communal dining in the central courtyard, and the remaining family members were ready to move on to more conventional American housing. The property came to the attention of Dolan and three of his friends, who purchased it collectively.

Today, the compound is a bustling community once more, housing 12 people ranging from age zero to 74 in cheerful white-clapboard houses bordered by a communal garden blooming with trumpet vines and climbing beans. While residents have expanded upon the original structures over the years, they’ve also densified the site with in-law units and studios for both living and working. The smallest of the four main dwellings manages to fit a two-bed, two-bath home into the modest footprint of a two-car garage — over three stories.

Since the San Francisco Bay Area began to shelter in place in mid-March, the residents of the old Salemi compound have found that the social contact and casual connections fostered by the shared outdoor space have been essential. “It’s saved my mind,” says Adriana Taranta, a social worker and one of the founding members of the community, who has been working from home. Otherwise, she says, “I think I would have snapped.”

Rightsizing the courtyard

Research shows that post-war suburbs, designed to house nuclear families in relative isolation, diminish casual interactions like the ones that are keeping Taranta sane. Americans who live in places that foster chance encounters with others — with walkable streets and close-in amenities — are twice as likely to talk with their neighbors as those who don’t. Less than one-third of these residents report feeling socially isolated, compared to 55 percent of people who live in places where happenstance interaction rarely occurs.

Living at the Salemi compound for 17 years, Dolan realized that its Mediterranean-style site plan fostered the kind of vibrant neighborly interaction that staves off isolation. The layout of the average American block — with front entrances around the external perimeter and private, fenced-off yards in the center — was essentially reversed here, where residents typically enter their homes through the commonly held central courtyard.

Having worked on at least 50 multi-family housing developments since 1985, Dolan has had time to experiment with different building scales, courtyard sizes and layouts. According to him, there are three main ways people interact with their neighbors: formal advances like knocking on the door, planned meetings at common destinations and unplanned interactions such as naturally crossing paths. It’s these last, most spontaneous interactions he believes are key to building community. “The way I know it’s working is when I see that people are leaving their doors open and wandering around barefoot, Dolan explains, “walking in and out of their neighbors’ houses.”

The secret to fostering this casual social cohesion is crafting the right scale of shared space, maximizing interaction while allowing for privacy and distance. Dolan cites courtyards of around 30 by 35-to-50 feet as a sweet spot. If the courtyard is too large, it starts to function like a quadrangle — people take different paths, missing those spontaneous encounters. “Beyond maybe six to eight or ten units maximum, you want a second courtyard, or a third. You want people to identify with that space, to feel like it’s ‘ours.’” He has also found that a mix of renters and owners generates a dynamic space. “You get some turnover, and a mix of people at different stages in their lives.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.While Dolan hasn’t designed these buildings specifically in relation to social distancing guidelines, he believes the courtyard community model will continue to work well for this need. Townhouses surrounding courtyards, which he has found to be especially desirable, can be built without common indoor elevators and corridors, minimizing the potential virus transmission vectors of surfaces and airspace shared by many families.

A 2015 study led by Jamie Anderson at the University of Cambridge’s Well-Being Institute found that living in such a neighborhood was linked to higher engagement with healthy behaviors. The study compared two Cambridge neighborhoods of “terraced” dwellings (equivalent to row houses): one laid out in a traditional British pattern with each home having its own small private backyard, and another where the majority of outdoor space was held communally in internal courtyards and community gardens. In the communal layout, where only 25 percent of homes had private outdoor space, residents were significantly more likely to connect socially.

These casual social connections can be especially useful in times of crisis. Research conducted by Daniel Aldrich, professor and director of the Resilience and Security Studies program at Northeastern University, has identified an under-appreciated factor critical to surviving disasters: how well you know your neighbors. Researching natural disasters like the 1995 earthquake in Kobe, Japan, Aldrich found that neighbors were responsible for saving more lives than fire trucks and ambulances.

Collective efficacy

When people see themselves and their communities as capable of dealing with a crisis, they are far more likely to engage actively with social and environmental challenges. This sense of common agency is known as collective efficacy. Would you mail a stamped envelope found in the hallway of your building? Will you wear a mask to protect the people around you from germs? These pro-social behaviours, combined with social trust and a common sense of agency, signal that a community has a high level of collective efficacy.

Thankfully, none of the residents of the Salemi compound have fallen prey to Covid-19. But many say they feel safer knowing their neighbors can keep an eye out for them. As Sally Baker, who suffers from chronic asthma says, “I always find flowers on my porch and containers of soup… and I don’t even know how people know [when] I’m sick.” The communal courtyard has been ideal for distanced socializing outdoors, without necessitating stricter safety measures virologists are recommending for denser “co-living” buildings such as scheduling phased use of internal common areas like kitchens.

For Taranta, the social network around the courtyard has been a critical support in past personal crises. “Our son was extremely sick when he was little and it was a super traumatic time for our family, and I think in a way, for everybody here. . . It helped a lot to have other people around. To help with our other son, but also to know what we were going through.”

To Tom Dolan, this “missing middle” model of housing meets a range of challenges caused by the pandemic: community with distance; remote work that doesn’t isolate; even the “social bubble” construct that some epidemiologists have endorsed as a way to socialize amid a deadly virus. Although the missing middle typically refers to mid-density dwellings, Dolan sees courtyard communities as providing another middle too often missing from both suburban and urban development: shared, central outdoor space.

“To me, this is the kind of building type that the world needs right now,” he says. “I’ve been feeling that for a while, but I think it becomes more true in the context of Covid. Being able to go in your front door and not come out for two days, but when you do decide to come out, you can interact — that’s what makes life complete.”