At the age of 55, Deepak Swaroop left his global role as a senior partner at an accounting firm to embark on a new path as a startup founder. Lacking the change and fulfillment he was hoping to find in this world, he then dabbled in retirement, only to feel unsatisfied by his new activities of golf, walks and trips to the library.

He’d read about Lucy Kellaway, the Financial Times editor who left journalism to become a trainee teacher and went on to found Now Teach, an organization that helps people change careers and become teachers, in 2017. After sitting in on lessons at five different schools, his mind was made up: He would retrain as a high school math teacher.

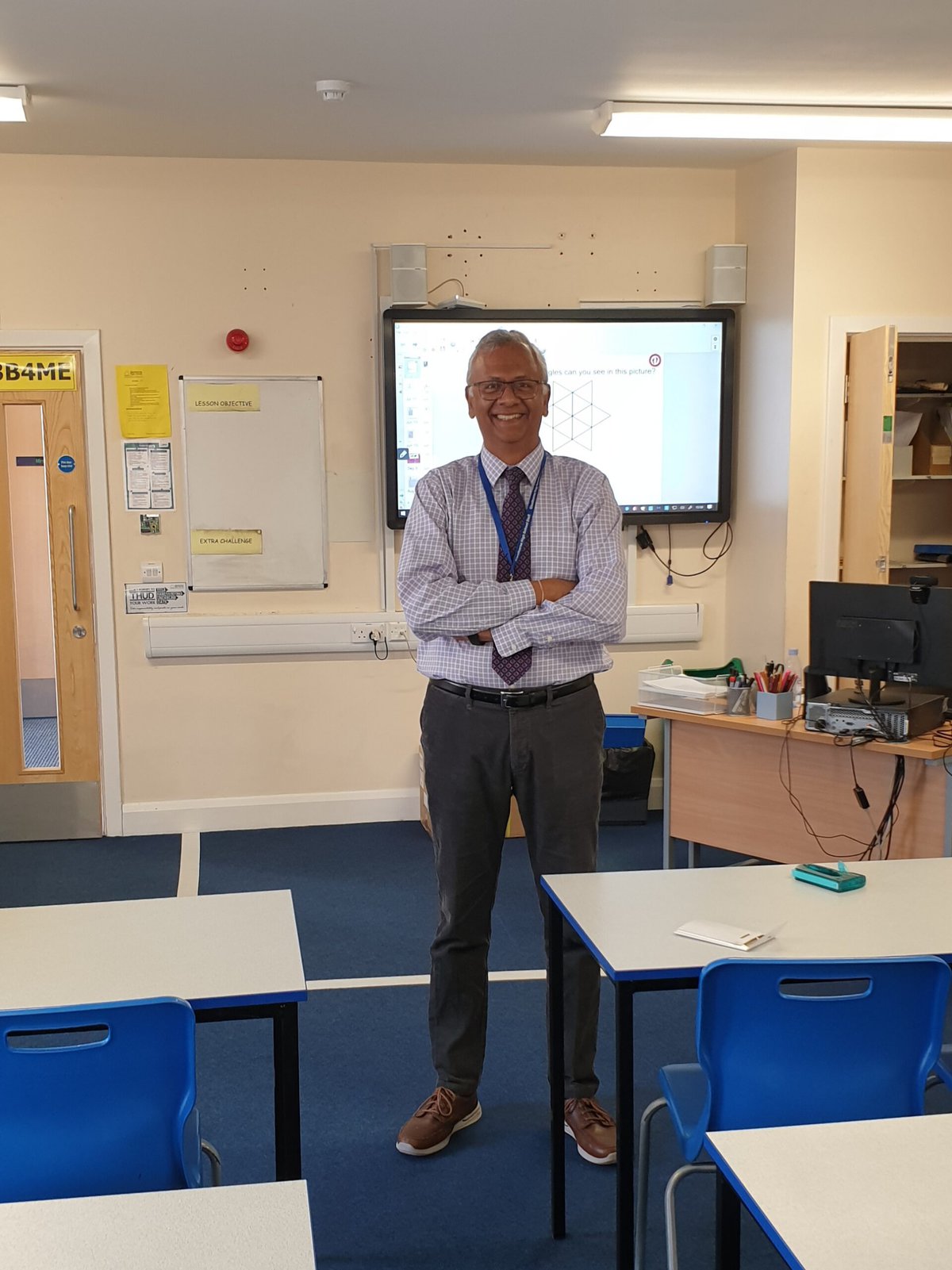

Three years on, Swaroop feels energized and inspired — even if he is now earning a fraction of what he used to.

“Money wasn’t really the make or break for this option,” says London-based Swaroop. “I was keen to do something which had a purpose, so I could contribute back to society in a way. My view was that I don’t think I can contribute a lot of money to charity, but I can definitely contribute my time.”

Finding a new purpose in the classroom

Swaroop is one of the 850 people who have left careers like finance, IT, medicine, science, engineering and more to retrain as teachers through Now Teach, which relies on both government funding and corporate donors. Now Teach helps them gain a Postgraduate Certificate in Education, which typically takes one to two years depending on whether it’s done in a full- or part-time capacity. Now Teachers are also encouraged to apply for the many scholarships and bursaries on offer.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.Teacher vacancies in England have doubled since before Covid, and the government is well short of its target to recruit new trainees, as the Guardian reports, fueled by a lack of pay increases and failure to improve the heavy workload and long hours, plus more attractive opportunities abroad.

But Now Teach, and second-career teachers like Swaroop, are playing a pivotal role in helping fill the country’s teacher shortage. The organization has hit on a winning formula by focusing on an otherwise overlooked segment of the employment market: the over 50s. The average age of Now Teach teachers, the organization confirmed, is 49, with the oldest being 70. Countries like Australia are also looking to midlife career changers to meet shortages of math, science and technology teachers.

As Now Teach CEO Graihagh Crawshaw-Sadler acknowledges, many will have taken a pay cut to pursue this new path, but they’ve reached a point in their life where their priority is satisfaction over salary.

“It’s not about the money, it’s about what this opportunity is affording them in terms of motivation, and knowing that they’re having an impact on young people,” says Crawshaw-Sadler. “We’ve got an awful lot of people who perhaps would have been looking to take early retirement, who are doing this instead. And then a large number who actually realized they’ve got a significant number of years left working. They’ve done what they want to in their current career, and it’s time to do something different. People are living and working longer, and they reach a point where they’ve given a lot to a particular profession, and they want to kind of make the next five to 15 years really count.”

This later life ambition is something Swaroop certainly relates to. “I just want to get into the classroom and teach,” he says. “I don’t have an objective of becoming a head of school. Previously, I would actively try to move up the ladder. That is being replaced by my desire to be more committed to my teaching.”

“I have had students write to me that I have helped them realize their potential and what path to take in the future. That is more valuable to me than money.”

Making schools more diverse

Originally from New Delhi, India, Swaroop is also proud to enrich the cultural diversity of his school, which, up until a few years ago, had a predominantly white teaching staff despite its highly multicultural student body. This reflects Now Teach’s success in attracting ethnic minority recruits at a higher rate than the national average and helping to close the representation gap between pupils and teachers. Thirty-two percent of its new trainees come from an ethnic minority, versus 19 percent of this year’s overall national cohort of trainee teachers and the overall national teacher rate of 21 percent, with 36 percent of pupils across the country being from an ethnic minority, according to figures shared by Now Teach. This equalizing effect also extends to gender: 44 percent of Now Teach’s intake this year were men, versus 30 percent nationally.

Indeed, Swaroop has often felt like the odd one out on the teaching staff. “My head of department is a 31-year-old man. He treats me with respect and shares things with me, but ultimately, I’m a junior teacher,” he says. “Initially, I would admit I found it challenging to be around such a young group of fellow teachers, who would think differently and would have different aspirations from me.”

Accepting that your age doesn’t match your seniority when you become a second career teacher doesn’t come easily, acknowledges Now Teach’s Crawshaw-Sadler.

“That’s the balance our Now Teach-ers have to find — being a novice, at the same time as being incredibly experienced. That’s one of the things we often focus on in the coaching support our trainees have with us, on how to tread that line and have the greatest impact, whilst also learning a brand new craft,” she says.

A healthy dose of humility, and adopting the view that people can lead multiple lives in one lifetime, has kept 56-year-old Beverly Melbourne grounded in her transition from government education policy advisor to high school English teacher.

Like Swaroop, Melbourne read about Now Teach in the Financial Times, and was ready to do a job where she could see and experience the impact of her actions. She retrained in 2022, and now, aged 56, is in her first year on the job.

She believes her colleagues and students appreciate the different perspective she brings based on her life experience.

“I’ve written policy, I’ve contributed to government speeches, I’ve done research. I can tell students how important it is to treat your colleagues well. I can tell them that soft skills are just as important as academic skills, because I’ve worked in meetings, created networks,” says Melbourne, who is based in the West Midlands region of the UK.

“Those other skills are just as important to produce people that will be successful, not just for themselves, but for others as well.”

She too has left behind her ambitions to climb the corporate ladder, instead valuing the emotional reward of having a direct hand in a young person’s future.

“When you make a difference in education, the ripple effects are everywhere,” says Melbourne. “When we’re dead and gone, nobody’s going to remember what we got paid. They’re going to remember how we contributed to our family and to other individuals.”