Earlier this week, we published a story about musicians who are diversifying classical music, one of the whitest genres in the arts. Privilege and class have long played a role in how culture is consumed, and by whom. Today, we explore what’s behind the remarkably strong links between education levels and involvement in cultural events.

Can an interest in theater and music predict whether someone will graduate from college? And if so, can introducing children to the arts put them on a path to academic success?

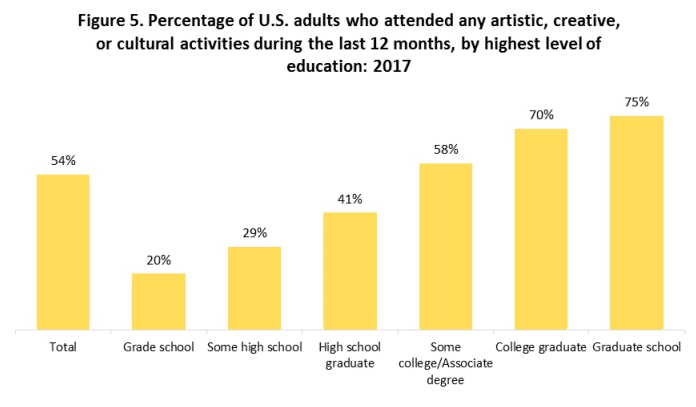

In January, the National Endowment for the Arts released its latest Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, which analyzes the various ways Americans interact with arts and cultural events. It’s a trove of data with more than a few surprising revelations. (For instance, one percent of Americans attend a live reading of poetry or prose every week — the mind reels.) One of its most thought-provoking findings has to do with education. As it turns out, how much schooling you’ve had is a near-perfect predictor of how much culture you consume.

The NEA’s report shows a direct correlation between the highest degree a person has achieved and the number of arts events they attend. (“Arts events” are defined broadly as plays, museums and concerts, but also live music in a church or nightclub.) Of the adults surveyed, 20 percent of those with only a grade school education attended an arts event in the previous year, while 40 percent of high school graduates, 70 percent of college graduates, and 75 percent of those with post-graduate degrees did the same. The pattern holds even for those who didn’t finish high school or college; the more years of education you have, the more likely you are to see a ballet performance, go to a craft fair, or visit a historic site. What’s more, this has been true since the NEA began conducting the annual arts participation survey in 1982, almost 40 years ago.

There’s a chicken-and-egg question here. Do elementary school art classes lead to PhDs? Or do people whose privileged backgrounds allow them to get the best possible education also have more opportunities to cultivate an interest in the arts (and the cash to afford subscription seats to the opera)? We consulted the experts to find out.

A question of access

“There is correlation here around opportunity,” says Sarah Johnson, director of the Weill Music Institute, Carnegie Hall’s education and social change initiative. “Who’s most likely to participate in [arts activities]? Kids who have plenty of resources and who are in good schools.”

Weill Music Institute, founded in 2003 as an umbrella for Carnegie Hall’s education programming, provides learning opportunities for children, teenagers and disenfranchised populations in New York City and around the world. Among their programs: a digital world music curriculum for young children, a program that links professional orchestras with local elementary schools, and opportunities for young artists to be mentored by famous musicians (including, this year, opera legend Renee Fleming and rapper Tariq “Black Thought” Trotter from The Roots.) The vast majority of their programming is free, accessible to students and educators at underfunded schools who may not otherwise have those resources. “We have been thinking about those issues around equity and access to opportunity a ton, for years, across all our programs,” says Johnson.

Here’s the good news: exposure to the arts has been shown to have a profound impact on all students, regardless of their socio-economic status.

The arts advantage

There is no major study that directly addresses the question of whether arts participation leads to higher education levels. There is, however, a whole lot of data about how the arts improve students’ performance and motivation in school, which, logically, may encourage them to go on to college and beyond.

Broadly, the arts have been shown to strengthen both reading and math skills. When drama is integrated into a language arts curriculum, students achieve higher levels of literacy and build better vocabularies. The study of music has been connected to improved math skills. Children who participate in arts have higher GPAs and perform better on standardized tests — ironic, since No Child Left Behind inspired many districts to cut arts funding and redirect their resources towards test preparation.

The arts advantage not only cuts across income levels, it can level the playing field. Disadvantaged students who are “deeply engaged in the arts” have been shown to perform better academically than students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds who are less involved in the arts. Even juveniles in the justice system are more likely to earn high school credit if they participate in the arts while incarcerated.

Not only do the arts improve academic performance, they enhance students’ overall experience of school. Young people who participate in arts programs report less boredom and are more likely to describe school as enjoyable. They feel more respect for their teachers and peers. They have fewer disciplinary infractions. They are less likely to abuse drugs.

All of these positives help students stay on track. Young people who are highly involved in the arts are five times more likely to graduate high school than those with low involvement, and students who study the arts are 29 percent more likely to apply to colleges than those who do not. So while no specific study has drawn a straight line from art classes to advanced degrees, the cumulative evidence is compelling.

What can’t be quantified

While the data is persuasive, it’s also not the whole story. The arts have the power to transform education in ways that are difficult to quantify, and some that researchers are only beginning to understand.

Educator and scholar Sarah Fine believes that the subjects we think of as extracurriculars, including the arts, often sculpt students’ intellect more effectively than core academic classes.

“In a lot of classroom classes, kids are constantly practicing isolated skills without ever really understanding how those skills fit together towards some authentic purpose,” says Fine. “There are very few opportunities to actually produce something that is distinctive and involves any sort of individual contribution, whereas in the arts, almost by definition, you’re creating something that ideally has some aesthetic or social value to the world.”

Fine’s book In Search of Deeper Learning: The Quest to Remake the American High School, co-authored by Jal Mehta, compares the experience of students studying Hamlet in English class to theater students at the same school producing the 18th century comedy The Servant of Two Masters. The authors observed that, in comparison with their classroom behavior, the students participating in the production worked harder, had a greater sense of purpose, built closer relationships to their teacher and were less self-conscious about participating. They also had more opportunities for collaborative work, and simultaneously achieved a spectrum of learning that is physical (building sets, performing), mental (learning lines, analyzing text) and emotional (exploring character arcs, building relationships with other theater kids).

Fine argues that some of these crucial life lessons — for example, learning how to use one’s skills in collaboration with students in different roles to achieve a common goal — are necessary to earn a living wage in the 21st century, and are not being adequately taught in most classrooms.

She also notes that it’s possible to attain these same benefits by participating in non-arts-based extracurriculars — for example, playing on a soccer team. But physical education isn’t being eliminated from public education at the same rate as arts programs, because sports are recognized as inherently valuable to a well-rounded education, just as Fine believes the arts should be.

Passing the baton

Given the research, one could extrapolate that exposure to the arts encourages students to pursue a higher education. But why stop there? Jeri Lynne Johnson, founder and conductor of the Black Pearl Chamber Orchestra, facilitates educational programs with children in underserved communities across Philadelphia. She believes that “part of the reason that we are in the political situation we are in” is that U.S. citizens feel powerless to even imagine a better society, let alone make changes. By facilitating creativity and a sense of agency, she theorizes, arts programs won’t just get kids into college — they may even save democracy.

“We have programs where we’ll go out, we’ll do a concert, then we put a baton in people’s hands and say, hey, come on up and conduct the orchestra,” says Johnson. “I give them a little conducting lesson. And to a person, they’re amazed that the orchestra really is doing what they tell them to do. They need to understand that when they move, that makes something happen. And so an orchestra as a living system becomes a metaphor for the political system, the financial system, the legal system, the educational system, and that people have the capacity to move and communicate in a way that affects that system.”

Read the companion piece to this story, This Is What Classical Music Looks Like.