In Telangana, an arid south Indian state notorious for drought, a man swipes a card at an ATM. Instead of cash, the machine doles out 20 liters of clean drinking water. The ATM is housed in an iJal (My Water) station, run by 31-year-old Somarathi Sindhuja, a petite mother of two. When she set it up seven years ago, she had not imagined that her seed money of Rs 2,00000 (just under $2400 US) would help her create what she today calls her “public service business,” which supplies clean drinking water within a two-mile radius of her home in Warangal, Telangana’s second largest city.

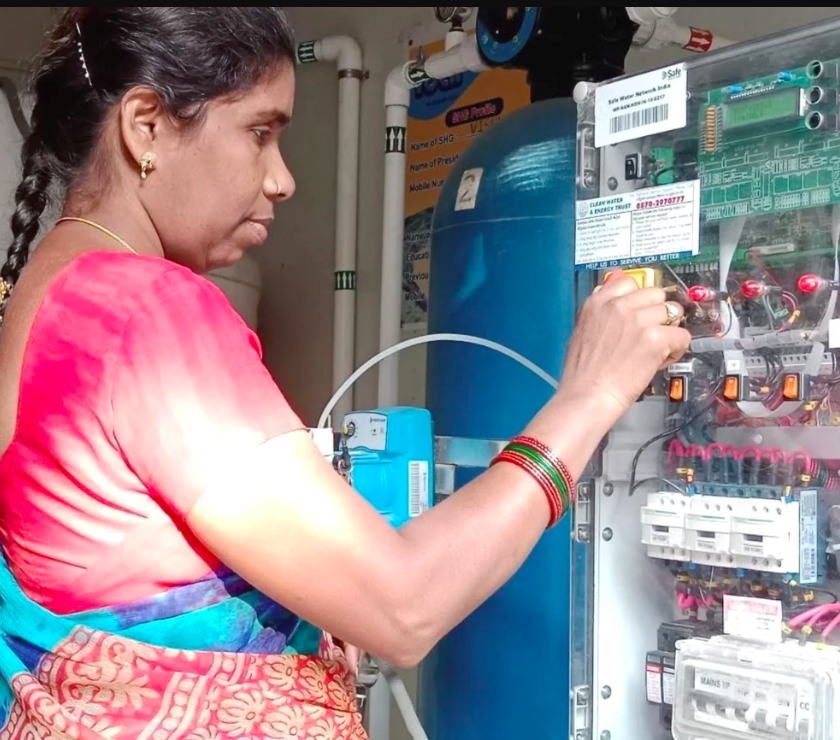

Sindhuja is one of the 350 rural water entrepreneurs trained and supported since 2017 by Safe Water Network (SWN), an American nonprofit founded in 2006 by the late actor and philanthropist Paul Newman and other civic leaders. The entrepreneurs buy or provide the space for the water filtration equipment and ATM, as well as the raw water. SWN provides them with the necessary training, technical support and water treatment expertise. Using all this, they are able to filter water to international safe drinking water standards and sell it for the nominal sum of Rs 5 ($0.07 US) for 20 liters.

That’s an extremely good deal for the community: Typically the price for a similar quantity of water, from a competing supplier like commercial tanker owners, is at least double this amount; bottled water can go for as much as 10 times more. It’s a good deal for the entrepreneur, too. “I earn about Rs 15,000 to 20,000 (roughly $180 to $240 US) per month from this, which is amazing as there are hardly any jobs available to women like me here,” Sindhuja says. “And I’m also improving the lives of people in my neighborhood.”

Warangal is undeniably parched, and the water that most residents there can easily access is not safe to drink. And it’s not alone in these challenges: Due to depleting groundwater reserves, erratic rainfall and poor civic infrastructure, an estimated 2.2 billion people across the globe were unable to get safe drinking water in 2022. In India, thanks to the government’s ambitious piped water scheme Har Ghar Nal ka Jal (Water on Tap in Every Home), things are looking up — but a lot more needs to be done.

“The piped water still needs to be filtered and treated before it can be drunk,” says Poonam Sewak, SWN’s vice president for programs and partnerships, pointing out that an estimated 63 million Indians lack access to safe drinking water, and half of the country’s groundwater is contaminated with fluoride, nitrate and heavy metals. The network’s iJal stations with attached water ATMs offer high-tech and decentralized safe water access solutions in India and Ghana.

Building a corps of rural water entrepreneurs

The network’s water ATMs operate in several districts in Telangana, Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh. Some are co-owned and run by self-help collectives of five to six women, while others are run by single entrepreneurs. The entrepreneurs provide the fixed assets and water source, usually a borewell on the premises. SWN contributes technical expertise to set up a reverse osmosis water filtration unit, provides marketing support and maintenance help and trains the entrepreneur to operate and maintain the water station and ATM. All in all, an iJal station costs under Rs 20 lakh (about $2,400 US) to set up and can service around 350 households. Sindhuja reckons she gets about 200 customers every day.

Creating clusters of iJal stations is crucial to this model, as this enables SWN’s technical staff to monitor and maintain the stations efficiently and cost-effectively. On average, each cluster with 30-plus stations creates about 60 to 100 jobs. This leads to what Kurt Soderlund, CEO, and Venkatesh Raghavendra, vice president, of the network described in an article in the Wharton School’s business journal as a “virtuous cycle, in which “[f]amilies participate, using more, safe water, leading to a healthier population and improved livelihoods.”

This is one of the many ways in which water entrepreneurship has been facilitated in underserved regions across Africa and Asia. While this model trains new business owners as well as provides technical and maintenance assistance, other models are more hands-off. For example, the for-profit African company Jibu has a network of franchises, which purify existing water sources in high-density communities and distribute water to the neighborhood within walking distance of their storefronts.

Jibu’s one-time paid transfer of water filtration technology to rural entrepreneurs probably costs less in terms of time, energy and money, compared to the SWN model, which continues to maintain the ATMS and handhold its iJal station owners through their working lives. Consequently, the stations’ water revenue does not cover all the costs — of water advocacy; monitoring, evaluation and maintenance; water quality testing; and field supervision costs — which are mostly subsidized by the network’s donors.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.This makes the SWN model highly dependent on philanthropic funding. In 2020, SWN’s biggest donor, Honeywell, decided to shift its funds to Covid relief and environmental sustainability. “We have other donors like PepsiCo, Oracle, Macquarie and Pentair Foundation, so there was no pause in our programs,” Sewak says. “But it was tough.”

However, this stream of funding is also why, as Sewak points out, Sindhuja’s and other ATMs have been working smoothly since 2017. “None of our stations have closed down,” she says. In some cases, she notes, stations have been “lifted and shifted” because the community wasn’t buying the water or because there were issues with the machine or the entrepreneur.

“Why should I spend on drinking water?”

Sindhuja says one of the initial challenges she faced was in convincing people that drinking clean water was imperative for their continued good health — even if it meant paying for it. Many other similar projects across the world have observed a similar hesitation to buy drinking water. “Some even said that the iJal water tasted different from the water from their wells and borewells,” she recalls.

To this end, SWN conducted large-scale outreach programs to educate people about the necessity of safe drinking water and improved the branding and signage at all their iJal stations. “We have also trained all our station operators to become safe water advocates,” says Sewak. Sindhuja uses her TDS meter (which measures the total dissolved solids in water) to show skeptical customers that the water from her ATM is cleaner than untreated water. Also, the palpable impact of drinking clean water has told its own story. An impact assessment report in 2020 found that the reported incidence of waterborne diseases among water ATM users in Telangana declined from 34 percent to 23 percent over a period of three years. Sixty-three percent of users reported a reduction in medical expenses and 73 percent, a reduction in school absenteeism.

Vanitha Baloth, 30, comes to Sindhuja’s water ATM every day to buy drinking water for her household. “My parents and I have been drinking this water ever since we moved to this neighborhood six months ago, and none of us have had diarrhea, dysentery or any other waterborne disease during this time,” she says. Baloth lives across the road, but in general, last-mile connectivity poses a challenge as customers still have to ferry heavy containers from the iJal stations to their homes. Sindhuja says she often helps elderly customers carry their water cans home.

Integrating water purification with doorstep delivery could help. For example, the Indian company Janajal (Hindi for “community water”) operates water ATMs in and around Delhi, as well as at several railway stations. In 2019, the company introduced clean fuel-powered three-wheeled vehicles that deliver clean water directly to communities, reaching both prime urban and deep, previously inaccessible rural areas. SWN “tried several water distribution models in India as well,” Sewak says, “but this increased the cost of the water.” It is worth noting that the network does operate a piped drinking water program in Ghana. In India, however, since the Indian government’s Jal Jeevan Mission already aims to provide tap water supply to every rural household by 2024, it is focusing on safe drinking water as the government water supply cannot be drunk without being filtered.

Another issue lies in the fact that the clusters of iJal stations are by and large dependent on groundwater extraction, which depletes a limited supply, and makes them vulnerable to any drops in groundwater levels brought about by climate change or overuse. “Today, as the government is moving towards water safety in its sustainable development goals, we have developed an automatic chlorination and online monitoring system, which digitally monitors and chlorinates water in the overhead water tanks installed by the government,” Sewak says. “This last-mile chlorination removes microbes that have contaminated the water as it is transmitted through pipelines, making it safe to drink.”

Meanwhile, Sindhuja is upbeat about the future of her “social business.” “Reverse osmosis filters are expensive to run at home. My water ATM offers a cheaper and equally good alternative,” she says. “Today, the iJal station supports me and my family, and together we support our entire neighborhood.”