This article originally appeared in Nexus Media News and was made possible by a grant from the Open Society Foundations.

For most of the Shinnecock Nation’s history, the waters off the eastern end of Long Island were a place of abundance. Expert fishermen, whalers and farmers, the Shinnecock people lived for centuries off the clams, striped bass, flounder, bluefish and fruit native to the area.

Today, the area is best known as a playground for the rich, where mansions sell for tens of millions of dollars. The Shinnecock community no longer lives off the water as it once did — rapid development, pollution and warming waters have led to losses in fish, shellfish and plants that were once central to the Shinnecock diet and culture.

That’s why Tela Troge, an attorney and member of the federally recognized tribe, started planting kelp.

Kelp is a large, fast-growing brown seaweed that sequesters carbon and harmful pollutants. It’s also full of nutrients and is used in foods, pharmaceuticals and fertilizers — making it a big business.

The global commercial seaweed market is valued at around $15 billion and is projected to reach $25 billion by 2028. In the United States, the kelp market is expected to quadruple by 2035, according to the Island Institute.

For the estimated 800 residents of the Shinnecock Reservation, where Troge said some families live on just $6,000 a year, kelp farming could be an economic lifeline. On one side of Shinnecock Hills, “you have billionaire’s row where some of the wealthiest people in America have homes,” Troge said. “Then, on the other side, you have Shinnecock territory, where 60 percent of us are living in complete poverty.”

In 2019, Troge, an attorney who has represented the Shinnecock Nation in federal land rights cases, was looking for a way to create jobs and clean up Shinnecock Bay. That’s when GreenWave, a nonprofit that promotes regenerative ocean farming, approached the community about starting a kelp hatchery.

Troge and five other women from her community formed the Shinnecock Kelp Farm, the first Indigenous-run farm of its kind on the East Coast.

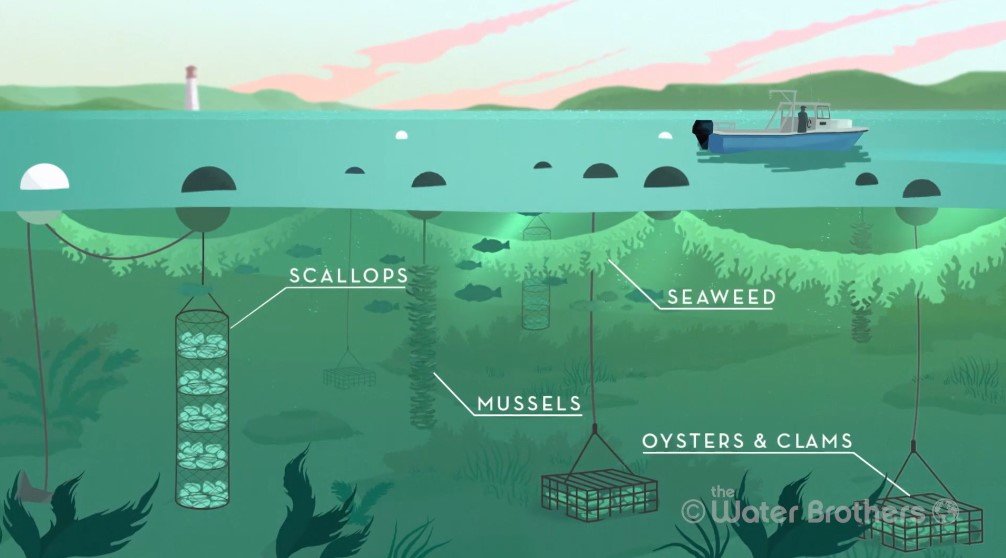

Greenwave’s model “so closely matched our skills, our expertise, our traditional ecological knowledge,” Troge said. The Shinnecock practiced regenerative ocean farming long before the term existed; they farmed scallops, mollusks, oysters and clams — all natural water purifiers — together with seaweed.

This system of kelp removing nitrogen near the surface while shellfish do the same down below creates powerful water filtration, said Charles Yarish, an emeritus marine evolutionary biologist at the University of Connecticut. It’s an ancient model. “If you go into Chinese literature, even to ancient Egypt, you will see examples of those cultures having integrated aquaculture,” he said.

Kelp feeds off excess carbon dioxide, nitrogen and phosphorus. The last two are pollutants responsible for harmful algal blooms that have killed off plants and animals in Shinnecock Bay, said Christopher Gobler, a marine scientist at Stony Brook University on Long Island. Kelp blades are lined with cells containing sulfated polysaccharides, essentially chains of sugar molecules that give kelp its slimy texture. These polysaccharides bind with nitrogen and phosphorus, pulling both out of the water and dissolving the nitrogen into a compound called nitrate. The dissolved nitrogen is what makes kelp a potent natural fertilizer.

Kelp forests promote biodiversity, lessen ocean acidification and remove dissolved carbon dioxide from the water. One meta-analysis by researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found that, on average, these farms remove 575 pounds of nitrogen per acre. (Projections based on another study, from Stony Brook University, put that figure at 200 pounds of nitrogen per acre.) Seaweed aquaculture could absorb nearly 240 million tons by 2050, equal to the annual emissions from more than 50 million fossil fuel — powered cars, according to a 2021 study published in Nature.

Compared to land-based crops, kelp requires very few resources — just spores, sea, and sunlight — and far less labor and harvesting equipment, said Halley Froehlich, a marine biologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. But, Froehlich added, kelp’s real superpower is that it grows quickly — faster than almost any other plant on the planet.

In December of 2021, Troge and her business partners started planting 20 spools of kelp off the shore of St. Joseph Villa, a retreat space just across the bay from the reservation. The villa, which offers easy access to the water, had once belonged to the Shinnecock nation. Today, it is run by a Catholic ministry known for its environmental and social justice work.

Troge and her fellow farmers ran the business out of a cabin donated by the ministry and encountered their share of challenges. It took longer than they had expected to find the right species of kelp — one that they deemed hearty enough for the hatchery.

“We got out later than we had hoped, as December is quite late,” said Danielle Hopson Begun, who co-founded the Shinnecock Kelp Farm. Sugar kelp is normally planted in the mid-fall, in time for a January growth spurt.

Then they suffered outbreaks of slip gut, a type of algae that grows on sugar kelp and suffocates it.

But by the spring of 2022, the Shinnecock women harvested 100 pounds of kelp, most of which they dried and sold as organic fertilizer. They donated their excess spores back to GreenWave, which distributed the excess to other growers. This was a small harvest compared to established kelp farms. Gobler, the marine scientist, estimated that a one-acre ocean farm could generate 70,000 pounds of kelp.

This year, the farmers plan to expand from 20 spools of kelp to 200. They are expecting a significantly larger yield and are exploring different uses for the crop, like food and cosmetics. They’re also talking with other hatcheries about exchanging spools of kelp in order to experiment with different species of seaweed. The farm is already cleaning up the area, Hopson Begun said; since operations began she said the water appears clearer and more birds fly overhead.

As Troge and her colleagues plan ahead, they’re also looking to bring on additional staff to help manage the harvests. They plan to hire from within the Shinnecock community. “I’m just really excited about building up to the point to offer people living-wage jobs,” Troge says.