Just two decades ago, the waterfront of Miani Hor, a swampy lagoon along the Arabian Sea coastline in Pakistan’s western province of Balochistan, was no more than a barren strip of land nearly devoid of vegetation. Today, it is awash with lush thickets of velvety green mangroves, their signature aerial roots poking through the lagoon’s brackish water.

The return of mangroves to Miani Hor is part of a vast ecological revival taking hold across Pakistan — one with huge implications for climate change. Hugging tropical and subtropical coastlines, mangroves are trees and shrubs that tolerate salt, thrive in wetlands and rank among the most endangered habitats on earth. More than a third of the earth’s mangrove area has been lost since 1980, destroyed for coastal development, chopped down for timber, or poisoned by industrial pollution. And although the rate of loss is slowing, mangroves are still disappearing three to five times faster than land-based forests — especially in Asia, where deforestation has massively increased over the past 30 years.

But Pakistan stands out as a notable exception. After losing as much as three-quarters of its mangrove forest over the past century, in the early 1990s the South Asian nation began restoring its mangroves. What began as a series of small, piecemeal efforts eventually grew into one of the most ambitious reforestation campaigns in the world. Now, under a nationally coordinated effort, Pakistan has restored vast swathes of degraded mangrove habitat and become one of the few places to have experienced a net gain in mangrove area in recent years.

“Pakistan got a lot right with mangrove restoration,” says Catherine Lovelock, a coastal and marine ecologist at the University of Queensland, Australia, and one of the world’s foremost mangrove experts. “It surely represents a blueprint for how other degraded mangroves around the world could be revived.”

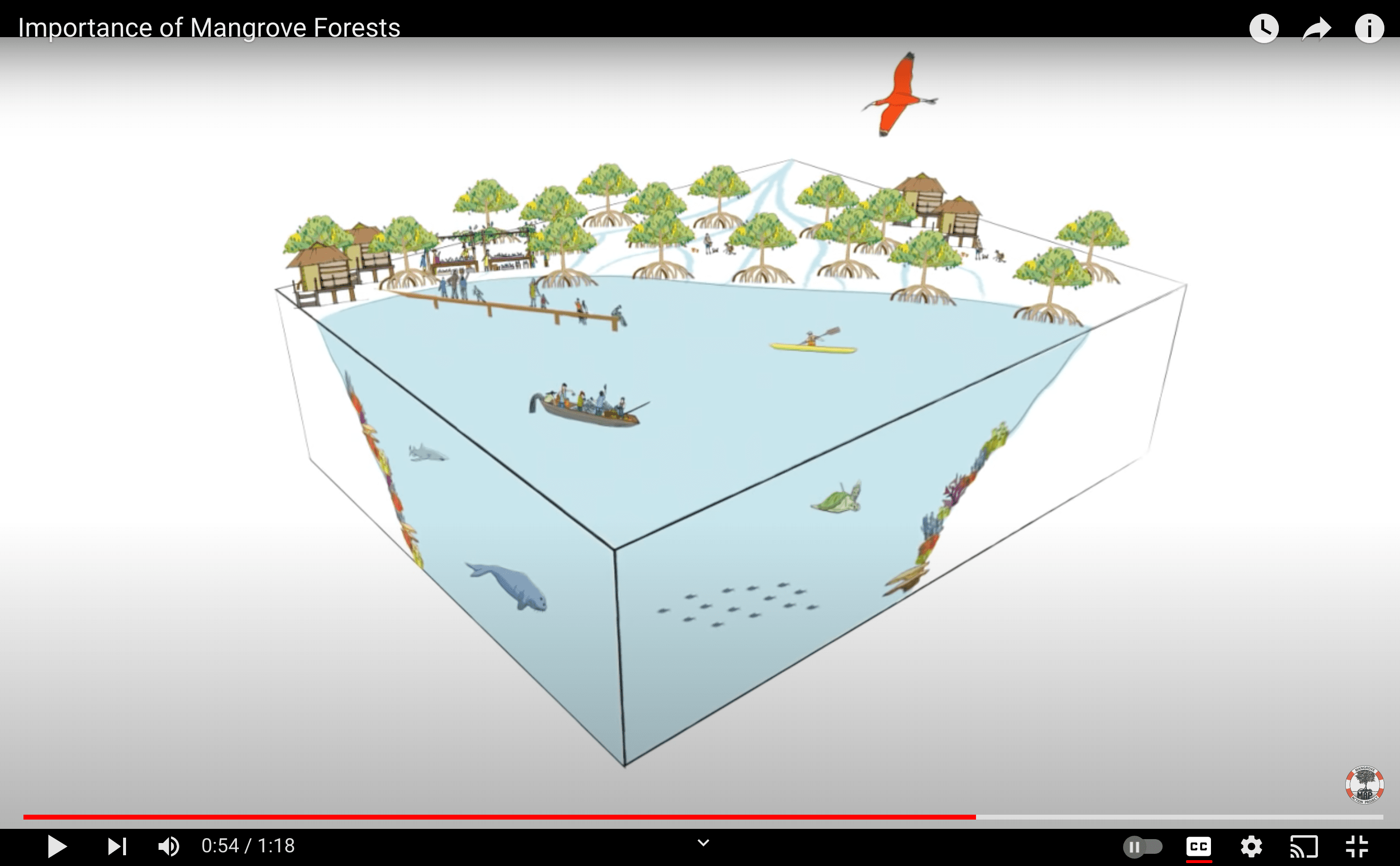

Often dismissed as dirty, mosquito-ridden tangles of roots standing in the way of an ocean view, these coastal jungles are in fact biodiverse sanctuaries with huge benefits to coastal regions. They are breeding grounds for countless species and provide food security for millions. They cleanse water by trapping sediments. They slow wave action, a major cause of erosion, and shield coastlines against storms and cyclones. Most importantly, they are highly effective carbon sinks, sequestering four times as much carbon as terrestrial forests do.

This is why, in the last decade or so, mangroves have increasingly been touted as a cost-effective, nature-based solution to climate change that can help countries meet their ecological goals. As a result, hundreds of thousands of acres of mangroves have been planted through restoration and rehabilitation projects around the world.

Yet such endeavors have frequently failed. A 2019 survey of over a hundred rehabilitation efforts in Thailand and the Philippines found that over half of the attempts had a survival rate of less than 20 percent, while another in-depth study showed that most of the mangrove restoration projects undertaken in Sri Lanka this century have had an average failure rate of 80 percent. The most common reasons for failure, those analyses found, were selecting inappropriate planting sites, planting in the wrong densities, and choosing species that are easy to plant over native ones that would do better in the long term.

Pakistan is the exception. The country has seen a three-fold increase in its mangrove coverage over the past three decades, going from 184 square miles in 1990 to roughly 565 square miles in 2020. The average success rate of mangrove regeneration efforts during that time was 80 percent or more, according to estimates by WWF Pakistan and the Pakistan branch of the International Union for Conservation of Nature Commission.

One of the keys to such large-scale success was the country’s step-wise, science-based approach to mangrove restoration, says Steve Crooks, a wetland scientist at Silvestrum Climate Associates, a consultancy that has helped design tree planting programs in Pakistan since 2015. “Pakistan has been working on mangrove afforestation on a small scale since the early 1990s and only recently has switched to bigger undertakings,” he says. “That gave officials time to familiarize with the process and get to know mangroves’ biological needs.” Crooks says that building this kind of institutional knowledge allowed Pakistan to avoid the most frequent missteps that hamper most restoration projects worldwide.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.

Critically, Pakistan also established legal protection for mangroves. “More often than not countries don’t have specific regulations to protect these ecosystems from threats that jeopardize their existence,” says Crooks. It imposed a countrywide ban on commercial timber harvesting in 1993 after deforestation was deemed to be partly responsible for the crippling floods that hit the country the year before. To help protect existing mangrove forests and newly restored patches, the provincial governments in the states of Sindh and Balochistan, where most of the country’s mangroves are found, also declared in 2010 all the forests within the Indus Delta region a “Protected Area.”

More recently, mangroves have even become a central part of the government’s ambitious Ten Billion Tree Tsunami campaign. Launched in 2019 by former cricket legend-turned-politician Imran Khan, the program aims to plant 10 billion trees by 2023, nearly a third of which are supposed to be mangroves. The initiative has attracted some criticism for its high costs, and Khan was ousted as prime minister in April. Still, his outsize plan seems to have already taken root as the new federal government has decided to continue the project.

Another element that played a key role in Pakistan’s successful mangrove restoration campaign has been the high level of involvement and support from local communities. “The participation of local people and their political representatives is vital for the conservation and regeneration of mangrove forests,” says Riaz Wagan, a chief conservator for the Sindh Forest Department.

To build public support, he explains that his agency has worked with local governments and environmental NGOs to create awareness about the importance of restoring the mangroves. Together they ran a series of community-engagement programs that involved activities such as planting and collecting seeds, looking after saplings and standing guard of newly planted areas.

Giving locals a personal stake in the effort was key to its success, points out Saeed ul Islam, assistant manager conservation for WWF Pakistan. With the support of regional forest departments, the organization set up a network of mangrove nurseries across the Indus Delta region over the past few years, hiring women and young people to grow saplings that are later sold back to both environmental nonprofits and government agencies, providing an important source of revenue in an area where nearly 90 percent of the population is estimated to live below the poverty line. “In many households, mangroves are now the only safe and assured source of income,” says Islam.

At the end of the day, he says, of all the ingredients needed for successful mangrove restoration – good science, strong government commitment, and support from local communities – the last is the hardest to secure, but by far the most crucial one. “The rehabilitation of mangrove forests can only be done on one condition, and that’s to put the needs of the people who call these places home first and find ways to make it pay off for them.”