Lawyers are one of America’s most distrusted professions, bringing up the rear behind even bankers and local politicians. But what if lawyers end up saving the world?

Scientists have been warning for years that mounting carbon emissions are dangerously destabilizing our climate. Efforts to tackle this urgent challenge through the political process have so far come up far short of the action needed to avoid some very bad outcomes.

Can litigation succeed where politics has so far failed?

We’ve actually been here before. Several decades ago it also seemed the tobacco industry was an invincible foe to public health. Over the course of decades, however, a series of long-shot lawsuits finally enfeebled this previously unassailable political lobby. Civil litigation against cigarette manufacturers began in the 1950s, but did not bear fruit until 40 years later in a series of court victories that culminated in the $206 billion Master Settlement Agreement with 46 U.S. states.

Terms of this judgment included halting advertising smoking to children, funding anti-smoking campaigns with industry money and dissolving three of the biggest tobacco industry organizations. Phillip Morris and other major cigarette companies were later convicted on racketeering and conspiracy charges for their decades-long conspiracy to deceive the public on the dangers of smoking. Lawyers went where no lawmaker had dared to go before.

Similar to the tobacco industry, the fossil fuel industry enjoys many powerful friends among American politicians. For example, Senator Jim Inhofe, the former Chair of the U.S. Senate Environment Committee, once published a book called The Greatest Hoax: How the Global Warming Conspiracy Threatens Your Future. The Trump Administration withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Climate Agreement and scrapped Obama’s Clean Power Plan. Scores of international climate gatherings seemingly accomplish little more than burning jet fuel.

But new evidence suggests that perhaps lawyers can succeed where policy makers have so far failed.

The tobacco and fossil fuel industries have a lot in common. They both enjoyed decades of power and influence. They have both engaged in highly effective campaigns in order to delay costly regulation of their dangerous product. In the case of cigarette manufacturers, exposed public deceptions eventually became their undoing when turned against them in a court of law.

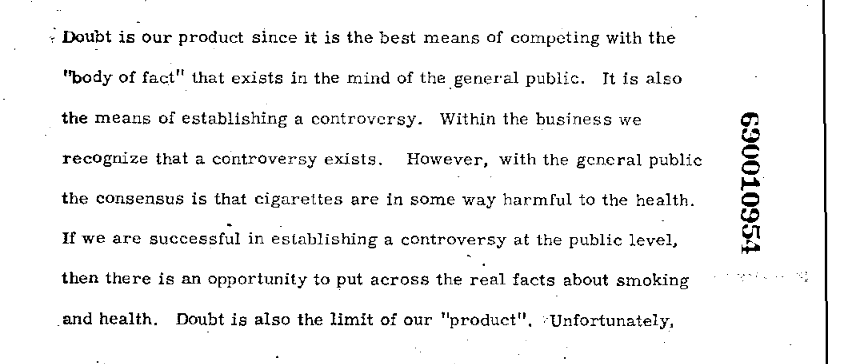

A notorious internal tobacco lobby document stated, “doubt is our product,” outlining how company-funded scientists and doctors are used “as a means to generate controversy” regarding the well-known link between smoking and cancer. These efforts might have bought them some time in avoiding regulation, but ultimately were their undoing when individuals and governments successfully sued companies for health care expenses and personal damages. As settlement costs mounted, the political power of Big Tobacco drained away.

Fast forward several decades and Big Oil is finally beginning to stew in the same pot. Court cases, even if unsuccessful at first, are one of the best ways to compel the production of potentially incriminating documents and evidence. Parties to a lawsuit are required to provide the other side a baseline of discovery information by either opening their file cabinets or through sworn deposition of key witnesses outside of court.

As such, a growing trove of damning evidence against the oil industry is being unearthed in a series of lawsuits and other investigations—much of which runs afoul of requirements that companies inform regulators and the public if they know their product is dangerous. The bigger the danger, the larger the obligation.

The fact that these documents are being unearthed is a huge win for the future of climate litigation—it is the first critical step in building the case against the industry that knowingly helped light the planet on fire. There are few dangers more pressing than our destabilized climate. Billions of dollars in potential damages are predicted by not only the scientific community, but by the oil industry’s own scientists. Adding to the tort lawyer allure is the fact that nobody has deeper pockets than Big Oil. We are still a long way from a legal feeding frenzy, but there is already some blood in the water based on what industry knew long before they said they didn’t.

Back in the 1970s Exxon wanted to be a leading research voice in the emerging field of climate change. They hired some of the best scientific minds of the day with generous funding and access to Exxon’s vast resources around the world. One team was using supertanker-based instruments to sample how much CO2 was being absorbed by the world’s oceans.

Their research was published in leading scientific journals. Former Exxon scientist James Black also warned senior management in a 1977 internal memo that doubling atmospheric CO2 would heat the planet by up to three degrees Celsius—similar to what scientists believe today. “Present thinking holds that man has a time window of five to ten years before the need for hard decisions regarding changes in energy strategies might become critical,” he wrote.

But management had other ideas than getting out of the fossil fuel business. By the early 1980s, internal research teams were fired and Exxon instead began investing in public relations. In 1989, Exxon helped fund the Global Climate Coalition and a constellation of other industry front groups in one of the most spectacularly successful misinformation campaigns in the long history of spin doctoring.

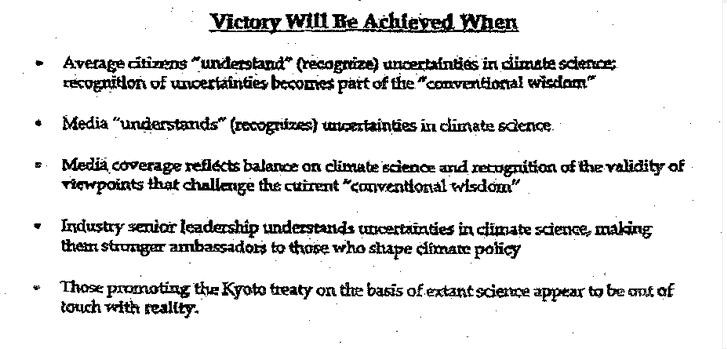

Similar to the strategies used by Big Tobacco, a 1998 internal memo from the American Petroleum Institute stated, “Victory will be achieved when average citizens ‘understand’ uncertainties in climate science” and when “recognition of uncertainties becomes part of the ‘conventional wisdom.’”

And it worked. By 2014, more Americans believed that climate change is due to natural causes than more than a decade earlier in 2001. Those who describe themselves as understanding global warming “very well” are also the demographic most likely to say it is not due to human activity.

Meanwhile, oil companies were quietly spending vast amounts of money upgrading drilling platforms and other infrastructure to withstand extreme climate and rising sea levels. If industry was certain enough about planet heating to invest in preparing for it, how does that square with what they told the public, the media and regulators for decades? Or their legal obligation to warn people if their product is dangerous? All of that could be a problem to explain to the jury.

So why is this good news? After all, whether or not the lawyers of the world ultimately succeed in holding the fossil fuel industry to account in the same way as cigarette manufacturers remains, to a certain extent, to be seen. It will be a long road no doubt with many setbacks. But on top of the mountains of documentation being unearthed in current court cases, slowly building the case against Big Oil, there is also already evidence that companies are taking note and altering their behavior.

Chevron became the first major oil company to disclose to shareholders their legal climate risk, warning investors of “increased possibility of governmental investigations and, potentially, private litigation against the company.” Royal Dutch Shell recently invested $2 billion in renewable energy technologies, the first stage of which was announced only days before the first US climate lawsuit was filed against the company. Exxon also joined a growing list of companies cutting ties with the Koch-funded American Legislative Exchange Council over the organization’s climate denial efforts.

Politics remains an overarching danger to successful litigation against large companies. Seeing what had happened to the tobacco industry, gun manufacturers realized that they could crippled by civil lawsuits for the use of their own (obviously) dangerous products. Instead they successfully lobbied lawmakers to pass a bill granting them indemnity from litigation. If fossil fuel companies succeed in the same outcome, suing for climate damages will be essentially impossible in the U.S.

In spite of these challenges, it would be a game changer if the world’s lawyers begin winning against the fossil fuel industry. After decades of terrorizing politicians, the tobacco lobby withered under massive legal bills and RICO charges for defrauding the American people on the dangers of smoking.

Legal judgments can also be more than about money. When Volkswagen was caught including illegal emission-evading devices into their diesel cars in the U.S., they were hit with $15.3 billion in civil damages. Interestingly, they were also ordered to spend $2 billion installing electric vehicle charging stations across America and prohibited from disputing the facts of the case anywhere in the world, lest they get sued some more. Imagine if oil and coal companies were likewise ordered in a settlement to tell the truth about their decades of misdeeds? Or, more importantly, to spend some of their billions mitigating climate change? Cases demanding this kind of action are already underway.

The law can be a blunt instrument, but also a heavy hammer. For some very smart lawyers, the oil industry is starting to look like a nail, and that’s a very hopeful thing.

This story is part of a collection called Sue the Bastards: Stories about hauling climate change scoundrels into court and suing their pants off. Read more here. Also in this series from Mitch Anderson, an interactive timeline of the most hopeful moments in climate litigation history… and present.