My visit to see the future of farming begins in an unlikely place, on the edge of a 60,000-square-foot insect farm in the suburbs of Vancouver, British Columbia.

I am standing inside what workers at Enterra, one of the world’s most commercially advanced insect agriculture companies, call “the love shack”—a humid warehouse where adult black soldier flies reproduce and the females lay up to 600 eggs at a time.

The love shack is an unnerving place to visit: black soldier flies do not bite (they do not have mouths; the adults subsist on a small abdominal fat sack), but they are not shy about landing and crawling all over you. Most are contained by netting and stacked vertically. Virtually no land is needed for breeding, which is happening all around me.

Enterra’s insect larvae (bug farmers prefer this to “maggots”) are technically livestock, making this, by population, one of the largest animal husbandry operations in the world—and part of an early-stage farming experiment that might be the start of the green future animal farming has been searching for.

In recent years, the $400 billion global animal feed market has grown hungry for alternatives to wild fish and soybeans, currently the two dominant animal feed protein sources.

And it’s about time alternatives came around. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization issued a report in 2006 that found livestock is responsible for 18 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Since then, they’ve discovered that it’s not livestock itself, but the food livestock eats, that produces almost half of those emissions.

About a quarter of the world’s commercial fish catch today—mostly forage fishes like herring, menhaden and anchoveta—are reduced into protein meal and oil to feed livestock and other fish. Meanwhile, soybeans consume vast tracts of deforestedland, and are grown with herbicides and other polluting chemicals.

Companies like Enterra are betting that this unsustainable link in the food chain will be gradually replaced by insect protein, which feeds on food waste and is carbon neutral. If a handful of fledgling global bug farmers can be successful, 2019 could be a make-or-break year for insect agriculture, and an opportunity to eliminate vast water and land pollution, protect forests and global fish stocks, and slash runaway greenhouse gas emissions.

It’s a simple premise: why feed our high-emission animals high-emission food when the world’s chickens, pigs, farmed fish and more can easily subsist on low-impact insect larvae that can be raised on the food and agricultural waste we currently discard?

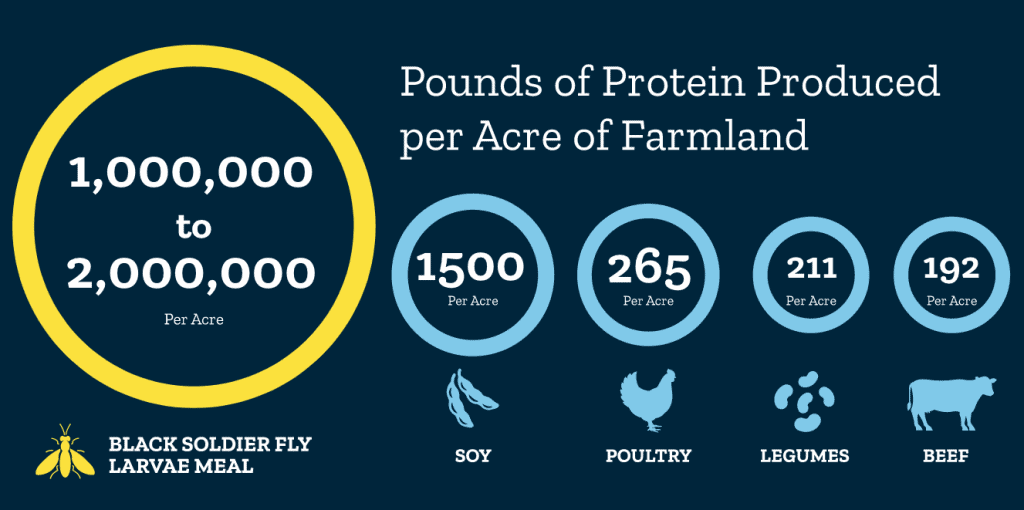

Enter the black soldier fly (BSF), a quick-to-mature, non-invasive insect that has a voracious appetite during its larval stages. At Enterra’s farm, they thrive on a diet of 100 percent pre-consumer food waste. The operation requires no water and a miniscule footprint of land, with negligible methane or greenhouse gas emissions.

“This is the future of food,” says Bruce Jowett, director of marketing for Enterra, a private Canadian company that sells farmed fly larvae products directly to commercial feed companies. “We are diverting food waste from the landfill, and black soldier fly larvae convert it into protein.”

On the cusp of a mass expansion, Jowett says Enterra will soon be ready to supply an industrial-scale stream of insects to a protein-hungry world. And they’re not the only ones.

The race is on

Enterra is one of at least six early-stage insect agriculture companies around the world—based in Europe, Canada, the U.S. and China—engaged in a race to prove their own proprietary approaches to farming insects can supply animal feed on the scale required to be commercially successful.

Most of them raise black soldier flies, which are super-fast to mature, and whose bodies in the larval stages are rich in fat, protein and calcium. Their larvae are pressed into a fat-rich oil; their bodies are ground into a high-fat/protein powder meal particularly good for aquaculture; and their molted skins and feces (called “frass”) are processed to make an excellent fertilizer.

EnviroFlight opened its first commercial-scale farm near Cincinnati last year, while Enterra is set to begin commercial production at a new CAD$30 million (about USD$23 million) 160,000-square-foot insect farm in Alberta this fall, with new farms planned for Greater Vancouver and Ohio in the next five years.

Europe is a particular hotbed, home to companies like England’s AgriGrub, which produces about eight tons of BSF per year for fertilizer and bird and reptile pet feed, and Protix, one of the biggest companies, with farms in the Netherlands and Asia.

InnovaFeed, a relative newcomer, has built the world’s largest insect production facility to date, producing 300 tons of insect meal per year in the north of France. But the company is scaling up, says spokesperson Maye Walraven, with a new facility opening in 2020 that is capable of producing 10,000 tons of insect meal annually—enough to feed 35,000 farmed salmon until maturity—with five similar-sized units planned for Europe, the U.S. and Asia by the end of 2022. This company made news earlier this summer when it signed a deal with Cargill, one of the world’s biggest agricultural food and animal feed companies, to jointly market its insect protein for the global farmed salmon industry.

The interest from Cargill, the biggest private company in the United States, bodes well for the future of the world’s nascent insect farmers. In 2015, Cargill paid over €1.35 billion (about USD$1.5 billion) to buy Norway’s EWOS, which produces about a third of the world’s feed for farmed salmon and trout.

“As aquaculture continues to grow, fish meal substitutes will be necessary, and this is where insects can play a key role,” says Cheryl Preyer, a spokesperson for the North American Coalition for Insect Agriculture, an industry trade group. “With amino acid profiles very similar to those of fish meal, insects can help by extending or replacing fish meal in those diets.”

Fish farmers could be forced to seek out protein from alternatives like insects sooner rather than later. Faced with dwindling wild fish stocks diminished by overfishing and climate change, the availability of wild fish is an open question moving forward. According to a June report by the FAIRR network of investors, warming waters in 2014 reduced anchovy yields in Peru, the world’s biggest exporter of fish feed. As a result, fish feed costs ballooned from $1,600 to $2,400 per ton.

Chickens, if given the choice, will devour all the bugs they can find, too. Last spring, Reuters reported that fast food behemoth McDonald’s is studying using insects as chicken feed to reduce its reliance on soy protein.

Helene Ziv, director of risk management and sourcing for Cargill’s animal nutrition business, confirmed that the InnovaFeed partnership will go beyond aquaculture, to include using insect protein to feed chickens and piglets, and to explore the unique health benefits of insect oil for farmed animals.

“With a population that is growing exponentially and finite resources on our planet, Cargill is proactively looking for alternative feed ingredients and new proteins to feed the world. We are therefore encouraging the emergence of several alternative ingredients which will enable a growing feed and food industry.”

Ziv added that the appeal of the BSF is that it can be produced in a sustainable way using agricultural waste—all at a cost that is competitive.

Insects are happy to eat the food waste that we humans discard or ignore, converting it into high-quality protein and fat. And herein lies the great promise of insect agriculture. Starchy waste from corn and wheat processing feeds InnovaFeed’s bugs; AgriGrub is involved with experiments to use marine algae as BSF feed; and for Enterra, their larvae gorge on pre-consumer food waste, otherwise destined for the landfill.

Along the way, huge reductions in greenhouse gases are possible. InnovaFeed has calculated that by feeding insect meal to animals, the company can eliminate 25,000 tons of CO2 emissions per year with each 10,000-ton-production facility it operates—the equivalent to taking 14,000 cars off the roads.

Back at Enterra’s farm, I visit a food mixing warehouse, where waste food—much of it discarded due to appearance or expiry date—is collected from bakeries, food processors and warehouses. (Jowett estimates 30 to 40 percent of all food produced for human consumption is wasted). There are dozens of watermelons on the concrete floor, piled crates of ripe Roma tomatoes and about a ton of fresh pasta. The food waste is mixed together and fed to the larvae in liquid smoothie form. Getting the right dietary balance is so important, Enterra has a nutritionist on staff to ensure the optimal mixture for health and growth.

After the larvae are cooked and dried, which kills the insects and any pathogens therein, they are pressed for oil and the remaining solids converted into a powdery meal.

The lucky one percent that escape the kiln or press end up at the love shack, where this journey begins all over again.

Niels van Swaemen / YouTube