“Alexa, kuki utumva Kinyarwanda?”

That question — “Alexa, why don’t you understand Kinyarwanda?” — would be easily recognized by some 12 million Kinyarwanda speakers in Rwanda, eastern Congo and parts of southern Uganda. But when directed at any one of the world’s three most popular voice assistants — Siri, Alexa or Google Assistant — the response is always polite yet perplexed: Sorry, I don’t understand…

That’s because, while Africa boasts over 1,000 native languages, each with its own unique accents and speech patterns, the three bestselling voice assistants can’t respond to a single one of them. It’s a blind spot that cuts off much of a continent from one of the fastest growing digital technologies there is, in part because African consumers represent a relatively minor share of the voice assistant market.

But just because a particular group of language speakers isn’t buying Echo Dots by the millions doesn’t mean that that language can’t be integrated into voice assistant programs. The ideal situation, according to Chenai Chair, special advisor for Africa innovation at the Mozilla Foundation, is “to be able to have voice data that can be used by anyone” — voice samples from thousands upon thousands of people speaking these languages in their native tongues.

Often, such large reams of voice data are proprietary, held by a few large for-profit corporations and used to train machine-learning algorithms. This makes it difficult for smaller developers, researchers and startups to get in on the voice-recognition technology game.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.To remedy this, in 2017, Mozilla, the non-profit tech company that created the Firefox internet browser, launched an open-source initiative called Common Voice. Aimed at democratizing voice data, Common Voice makes it easy to donate your “voice” — your language, accent, intonations and speech patterns — to a publicly accessible database.

Donating is simple. On Common Voice’s homepage, there are two options: “speak” and “listen.” Clicking on the former ushers contributors to a page where they can record audio samples. The contributor is given sentences to read aloud, with the option to play them back before submitting. The “listen” option allows participants to validate the accuracy of already donated voices on the platform.

This minimalistic user interface requires little technical ability. Participants don’t even need to register or identify themselves. Essentially, Common Voice is crowdsourcing the everyday speech of thousands, and then asking thousands of others to verify that those contributions sound correct.

The platform includes 90 different languages including two other Indigenous African languages: Luganda, spoken in Uganda, and Kabyle, a Berber language spoken in Algeria. The multi-language public domain holds more than 9,000 hours of voice data in these languages, with more than 166,000 people worldwide contributing to the project as of May 2021.

A deluge of data

Kinyarwanda was added to the Common Voice platform two years after it launched — its first native African language. In February 2019, Mozilla and the German development agency GIZ co-hosted an ideation hackathon in Kigali. The goal was simple: To come up with a concept that would encourage native Kinyarwanda speakers to donate their voice data to the Common Voice project.

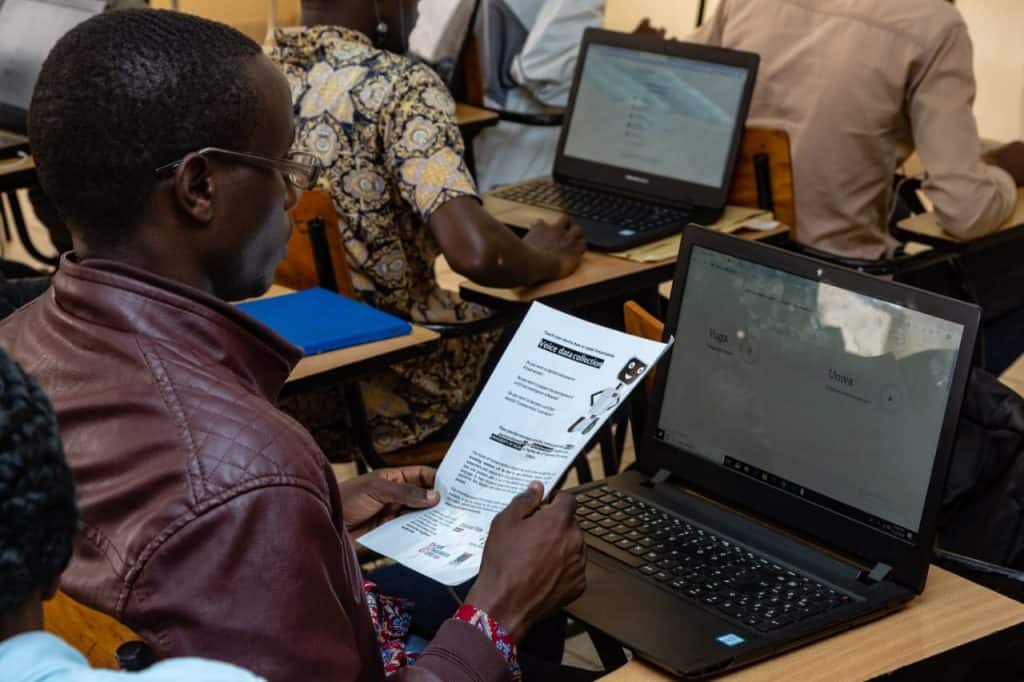

The winning concept centered on an idea familiar to all Rwandans: “Digital Umuganda.” Umuganda is a unique national holiday that takes place in Rwanda on the last Saturday of every month. On this day, people across the country gather in their communities and work together to build physical infrastructure like schools, roads and health care facilities. The idea behind “Digital Umuganda” was to adapt this concept to build a different kind of infrastructure — voice data — every month at universities, tech hubs and community spaces.

“It was more like gathering people from different universities and telling them the benefits of voice technology in their native languages.” says Remy Muhire, Common Voice Kinyarwanda’s community lead.

According to Muhire, prospective contributors were sold on the idea of inclusive technology and innovation, often by personalizing the issue. For instance, contributors would be told: “Imagine your grandma speaking to her feature phone to switch on the light outside instead of actually moving? Or running a Google search in your native language, or talking to Siri in your local language?”

The Digital Umuganda messaging appears to have worked — so far, 1,700 hours of Kinyarwanda voice data has been donated by over 840 contributors, making it one of the fastest growing languages on the Common Voice platform. Cultivating this large volume of source material is critical to making a language work correctly on a voice assistant device — machine learning requires lots of training. All the data that Common Voice collects, not to mention the platform itself, are open source and free for anyone to use, from scientists working on linguistic projects to large for-profit corporations.

The Mozilla Foundation’s Chenai Chair emphasizes that contributors’ privacy is a priority — the data collected from them is both minimal and anonymous. Certain basic types of information, like age and gender, help the project ascertain how a certain demographic speaks. While working in the community, says Chair, “Whatever data is collected, we ensure the safety and security parameters so that it doesn’t end up being misused.”

Since the beginning of the pandemic, contributions to the Common Voice project have moved entirely online. While this removes the hassle of organizing physical events, it highlights issues of internet access and affordability. Pre-pandemic, spaces used for data collection events were equipped with strong wifi connections. Now, some would-be participants are stymied by poor or expensive connectivity issues. Also, lack of supervision or in-person instruction can lead to poor quality data donations.

“Working in NLP [natural language processing] for low-resource languages is a challenging task in and of itself, because of a lack of data,” says Kathleen Siminyu, Mozilla’s Kiswahili machine learning engineer. “I will say that data quality is a key factor that does not get as much ‘airtime’ as data quantity.”

“It is a challenging task but good quality data would give us a huge advantage, which is why how we engage with the communities at the point of data collection will probably be the most important step of this entire pipeline.”

As it compiles data on languages long neglected by big tech, Common Voice is aiming to avoid the mistakes that contribute to the growing problem of AI bias. For instance, voice recognition tends to work better for men than for women, and often struggles to understand people with accents varying from those considered standard.

“From a common voice perspective, what we are doing is thinking about it from a design perspective which will include ensuring we have representative datasets or data samples that represent both men and women,” Chair says. Inclusivity, she says, must be fundamental to the process, “from design to collection to implementation.”