A number of recent initiatives have shown that a one-time gift of money to poor or homeless folks often allows them to permanently and meaningfully improve their lives. The studies that show the positive results of these projects disprove a myth that has often been used to argue against free cash: that people will simply squander it rather than spend it responsibly and effectively.

In Vancouver, the Foundations for Social Change conducted a pilot initiative called the New Leaf Project in which homeless people were given CAD $7,500 (USD $5,800) as a one-time gift. Recipients were screened and not all were accepted — people with severe addiction or mental health issues were not eligible, for example. All recipients were asked to think about how they could best use the money to move their life forward. Some proposed fixing up their cars so they could get to and from a job. Others bought computers, and some planned to start their own businesses.

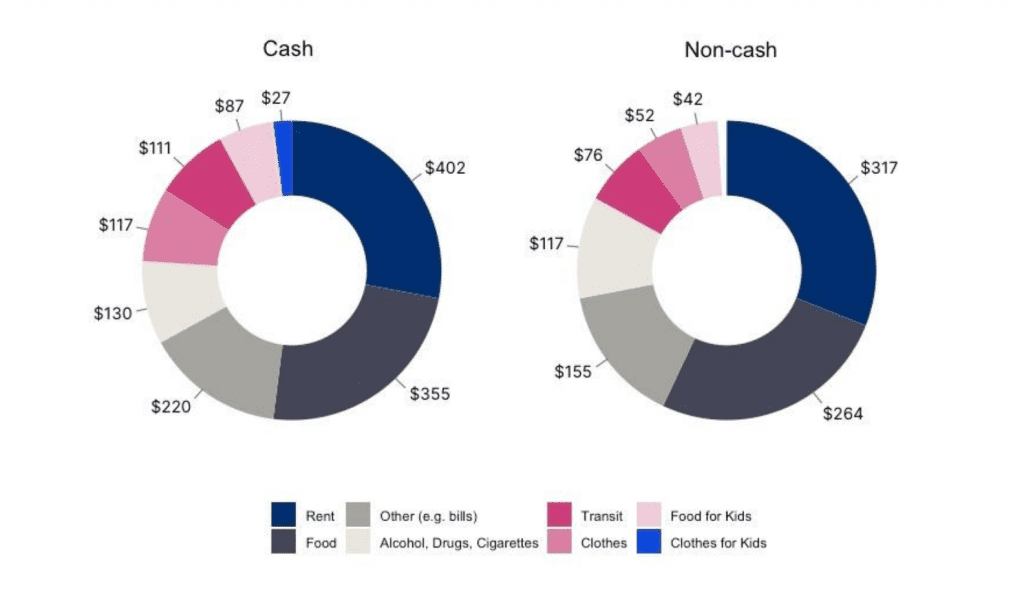

Some of these folks received ongoing coaching and, for comparison, others did not. About half of them participated in a workshop and the study results showed that they used the cash to improve their situations dramatically. They moved into stable housing, became food secure, and after a year many still had around $1,000 of the money tucked away in savings. They dispelled the myth that the money would be misspent — they actually reduced their spending on alcohol, cigarettes and drugs by an average of 39 percent.

Receiving a lump sum seems to provide a kind of jump start to people’s lives that the usual incremental assistance doesn’t. A lump sum is transformational and it instills in recipients a sense of empowerment, of choice and of dignity. This approach also cuts through much bureaucracy, as the recipients have to manage the funds themselves.

Vancouver’s New Leaf Project was a test to see if a one-time gift could make a difference. The results seem to show that in most cases it works, though only if the recipients are in a position to benefit from it and if there is infrastructure they can plug into: public transportation, affordable housing, fair credit ratings and alternatives to fast and junk food.

Around the world

The Foundations for Social Change was not the first to give this approach a try. A century ago, many U.S. states had something called Mothers’ Pensions, which were cash transfers for mothers who were single or whose husbands couldn’t work.

A recent study of the effects of the program found that:

Male children of accepted applicants lived one year longer than those of rejected mothers. Male children of accepted mothers received one-third more years of schooling, were less likely to be underweight, and had higher income in adulthood than children of rejected mothers.

In 2010, a British charity called Broadway gave 13 homeless folks in London $1,277 each. All of them had been living on the streets for at least four years when the project started. A follow-up study found that 11 of the 13 ultimately moved into housing. That’s not a big sample size, but it is additional evidence of success.

In 2014, Christopher Blattman wrote a New York Times op-ed describing how he worked with the Ugandan government to give out $8,000 to poor folks to put toward a business proposal. When Blattman followed up four years later he found that most of the recipients invested in learning trades like carpentry, and their earnings were 40 percent higher than the control group.

However, when Blattman checked in again after nine years it seemed the control group had mostly caught up. The cash recipients did accumulate more assets and they and their children were healthier, but after nine years they were not earning more. It seems the gift accelerated the progress of those who were motivated rather than being solely responsible for it.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.A similar initiative in Mexico, the Prospera cash transfer program, had positive effects mainly on the children of recipients — better health, more education and eventually better jobs.

Blattman also worked on a cash giveaway program in a poor part of Liberia. Here the recipients were given just $200. They spent it wisely — mostly on food, clothes and adding minutes to their phones — but it was not enough to put them over the threshold to true self sufficiency. It takes a substantial amount for one to get both feet on the ladder out of poverty.

Issues and questions

So, does this imply that all we need to do is hand out free cash and let the recipients figure out everything for themselves? I suspect not exactly. Folks are smarter than they are given credit for, and that needs to be acknowledged. But the rungs on the ladder have to be in place for a person to gain a foothold.

The programs described above were paired with other kinds of support: workshops, job training programs, subsidized housing, affordable public transportation to and from jobs, decent low-cost or free medical care, and in some cases, child care for single parents who became working parents. Without that infrastructure folks can’t really put the money to use. In Uganda, for instance, carpentry mentors were available to help recipients learn the skills they needed. An ecology and infrastructure are key — cash alone won’t do it.

If that ecology is present, and if folks are given a substantial enough amount of money — enough to really allow them to create and sustain a change in their lives — then it appears they do come up with a plan, a roadmap to raise themselves and their families up. They know how to manage their money and time given the opportunity.

With renewed dignity and confidence folks who were counted out often realize their hopes and ambitions.