When Aisha Bekele’s (not her real name) daughter was 14, she was abducted on her way to school, raped and forced to marry the man who did it. Scared the same thing would happen to her 12-year-old, Bekele kept her younger daughter at home in her southern Ethiopian village to protect her.

It was only when the mother of two heard a radio program about marriage by abduction on Yeken Kignit (“Looking Over One’s Daily Life”), a soap opera that was broadcast across Ethiopia between 2002 and 2004, that she learned that not only was the practice common in the region, it was also illegal.

Empowered by this knowledge, Bekele and a group of other villagers — many of whom had also listened to the show — came together to condemn the practice and work out ways to prevent it, and Bekele felt able to send her younger daughter to school again.

Bekele’s story is one of many that Population Media Center (PMC) tells to demonstrate the impact of its work. The U.S. nonprofit, which tackles social, health and environmental challenges using entertainment-education soap operas on radio and TV, has created more than 40 shows in over 20 languages since it launched more than two decades ago, broadcasting them to 50 countries and reaching more than 500 million people.

“People do not go home at night to listen to public health messages, they go home to relax and be entertained by the mass media,” says PMC founder William Ryerson. “Using charismatic characters in serial dramas to role model healthful behaviors has been shown over and over to influence large audiences to adopt new social norms.”

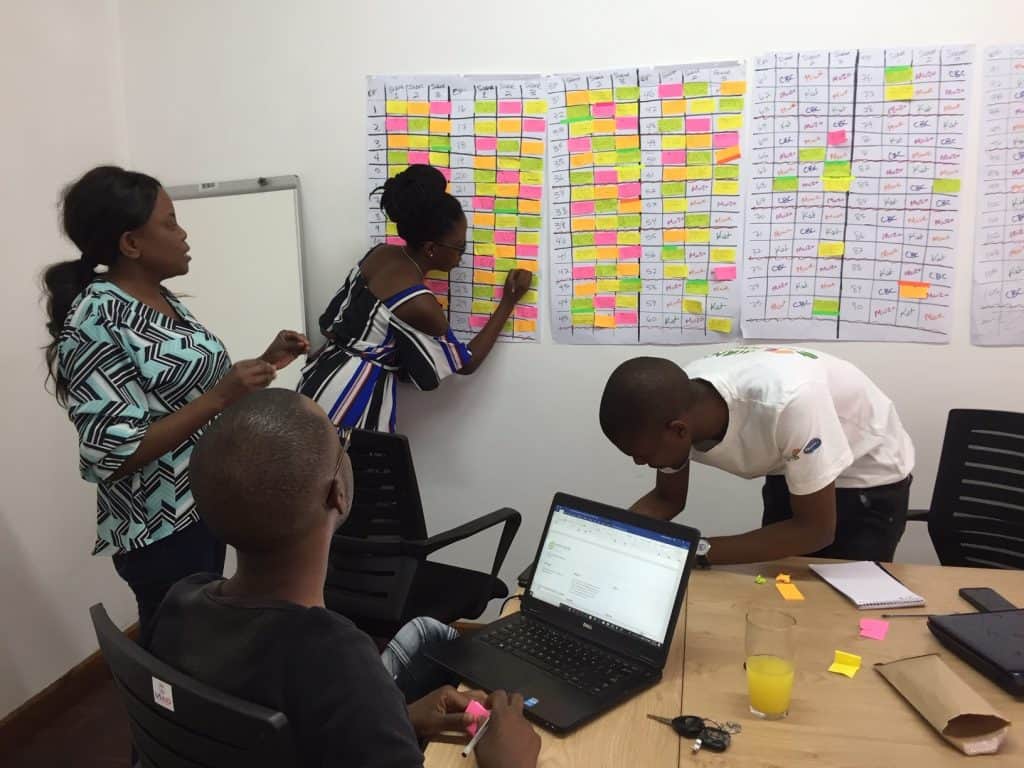

While the plotlines of programs like Yeken Kignit might appear straightforward, their simplicity belies the significant work that goes on behind the scenes. Before creating a new radio or TV soap, PMC researchers go into the field to do quantitative and qualitative research, interviewing culture experts to learn as much as they can about the place and its people, from the challenges they face to what they like to eat for breakfast.

Based on this ethnographic research, PMC chooses the main theme, or themes, of the show — Yeken Kignit’s marriage by abduction, for example — checking that the messages they intend to advocate align with government policies and programs available to the intended audience. If there is no reproductive health clinic in the broadcast zone, for example, PMC will not address reproductive issues that require visiting a clinic.

PMC then hires local writers, training them in an entertainment-education methodology established by Miguel Sabido, former vice president for research at Televisa, a Mexican media corporation. Sabido’s approach, founded on psychological principles of behavior change, gave rise to a communications strategy that uses mainstream media to educate the public on social and health issues. Among his accomplishments, his telenovela Ven Conmigo (”Come With Me”) is credited with increasing enrollment in state-run literacy classes by 63 percent to over 800,000 students.

Once PMC’s writers are trained, it is their job to develop a plot with three types of characters — positive, negative and transitional. The former advocate for positive values and negative ones criticize it, but it is the transitional characters, whose attitudes evolve over time towards positive values, who tend to be the most influential, according to Ryerson.

The shows are broadcast over at least a year, enabling such character development and giving audiences time to get accustomed to the messages.

“Parachuting a feminist leader to Sudan would be too radical,” says Ryerson. “It is better to bring permanent change in baby steps. If we do it too fast, the radio gets switched off and people get angry.”

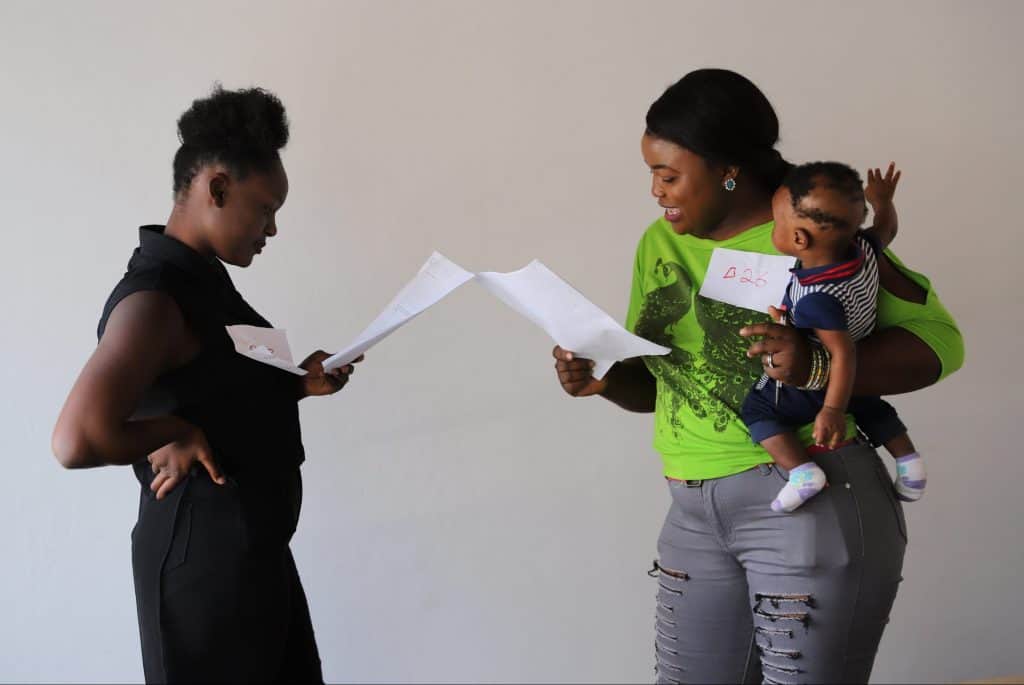

To be as culturally relevant as possible each PMC show is produced by local professionals in the local language, played by local actors, and set across rural, urban and semi-urban locations so that everyone can identify with at least one of the characters. As the show evolves, the writers incorporate audience feedback and real-life events happening in the country in question into the storyline.

To measure the impact of its work, PMC uses a number of methods including nationally-representative household surveys conducted once a show has ended. These compare knowledge, attitudes and behaviors between listeners and non-listeners. The nonprofit also tracks use of a particular service, such as a health clinic, during a show’s broadcast to discern if the program is helping increase real-time demand.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.While paying for the likes of prime time airtime and professional actors is more expensive than, say, a billboard campaign, PMC is convinced that the impact of their soap operas makes them a cost-effective way to bring about positive change in low-income communities.

Ruwan Dare (“Midnight Rain”), a PMC radio drama that aired in four northern states of Nigeria between 2007 to 2009, reached an estimated 12.3 million listeners (over 70 percent of the local population) and is believed to have led to 1.1 million new people adopting family planning methods, among other outcomes. Even though the show cost $1 million, funded in part by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, PMC calculated that the cost per person for those who adopted family planning and attributed it to the program was only 30 cents.

As well as the measurable impacts of PMC’s work there are the anecdotal ones, such as the Burundian father who says that the popular three-season serial drama Agashi (“Hey! Look Again!”), which aired between 2014 and 2016 and which addressed family planning, reproductive health and HIV/AIDS, helped him talk with his family about issues normally considered taboo.

“There are things I don’t feel comfortable talking about,” he said in a video about PMC’s work. “The serial drama helps me educate my children.”

Entertainment-education has its critics among scholars who find fault with it for focusing too much on individuals and their power to change themselves rather than on complex sociocultural and economic underlying factors that might influence an individual’s behavior.

Critics also highlight that development communication interventions are based on the concept of modernization, a process through which countries adopt Western political, economic, cultural and health systems. They argue that the main factor that impedes development is not lack of knowledge but global patterns of power and exploitation as well as structural inequalities and power relations within countries.

While acknowledging these concerns, Shereen Usdin, a founding member of the Soul City Institute for Social Justice, which uses popular culture for social change (and which has no affiliation with PMC), says that entertainment-education isn’t itself a negative thing.

“Historically, many entertainment-education programs were used by the Global North to educate people in the Global South about issues such as family planning,” says Usdin. “Their agenda was questioned as to whether this was about fertility control or genuine interest in women’s reproductive rights. But people have learned from stories since time immemorial in all cultures. We have found that creating local stories that are not victim blaming and that focus not only on the individual is extremely powerful.”

Traditionally, PMC focused more on individual behavior change. In recent years, the organization, like many leading entertainment-education practitioners, has moved towards approaches that focus on structural barriers. PMC has also been trying to cooperate more with communications researchers to help them understand the importance of social norms.

For an upcoming project in Liberia, where a three-year ban on female genital mutilation was recently announced and national elections are scheduled to take place next year, PMC is working with an NGO on the ground to address gender equity, sexual and gender-based violence, and social cohesion and conflict resolution.

There are times when the impact of PMC’s work is immediately evident, as the story of Agness Kaonga, a 23-year-old mother of three from Zambia, demonstrates.

“I had my first child at the age of 16 and my second son came soon after that,” says Kaonga. “While listening to Kwishilya (“Over the Horizon”) I learned that I could use contraception to space my children and use the time to take better care of my two children. Our third son was born four years later, allowing us to save money for clothes, food and school equipment.”

In many cases, however, working to change norms can take a long time, says Joe Bish, director of issue advocacy at PMC.

“While our efforts may not be as immediately tangible as the work of other developmental organizations,” says Bish, “which may be providing health clinic services or building physical infrastructure like school buildings, we are trying to bring long-lasting, transformative impacts to the health and wellbeing of future generations.”