By 2018, Tasha G. was tired of the hassles of renting. A single mother of two boys, the 37 year old from Broward County, Florida grappled constantly with her negligent landlord, who she says would rarely make basic repairs to her apartment, even while the threat of him raising the rent beyond what she could afford loomed constantly.

Tasha, a medical coder, picked up a second coding job, with which she paid off her credit cards and saved up $5,000 for a down payment on a home. But even with her good credit and that cash on hand, she couldn’t afford the appraisals and inspections that home sales require and found herself locked out of the local real estate market.

Frustrated but undeterred, she continued to work, save and educate herself. Her research turned up a company called Down Payment Resource that connects prospective home buyers with local, county and state programs that help people buy their first home. Tasha applied to the Florida Housing Finance Corporation’s down payment assistance program and, after taking a home buyer’s education course, was able to get a $7,000 forgivable loan towards her down payment.

The down payment loan plus the $5,000 she’d saved allowed Tasha to pay for a down payment and closing costs on a condo. The mortgage and HOA fees are about the same as her old rent. Tasha and her boys just celebrated their one-year anniversary as homeowners.

“Without the down payment assistance I don’t think I would be in the home right now,” she says. “It means a lot [to own my home]. I’m already starting to see how the value of my condo is going up. It’s amazing.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.Florida’s is one of more than 2,500 local and state down payment assistance programs meant to help mostly low-income and first-time homebuyers surmount a hurdle that often keeps homeownership out of reach. Now, if legislation working its way through Congress makes its way into law, that patchwork of programs could be complemented by a national down payment assistance program to help more Americans leap that hurdle.

Proponents see down payment assistance as a method to help narrow the country’s intertwined racial homeownership and racial wealth gaps. Thanks to decades of discriminatory lending practices like redlining and outright bans on home sales to non-white residents, today there is a stark gap in white and Black homeownership in the U.S. Some 44 percent of Black families own their home compared to 74 percent of white families. Many factors contribute to the persistence of this problem, but one big one is the down payment, a large lump sum of cash that often requires a degree of privilege to scrape together.

“We don’t have a mother or father to give us a down payment,” said U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Secretary Marcia Fudge in her Senate confirmation hearing last January. By “we” she was referring to communities of color. “We don’t have the wherewithal, the same kind of income, the same kind of access. It is like we were starting out of the blocks with someone who was ahead of us by 100 yards.”

The $1.7 trillion Build Back Better Act would give people of color and other lower-income Americans a chance to catch up in the housing race. Recently passed by the House of Representatives, the Act includes $10 billion to help first-generation home buyers get a foothold in the housing market.

If the Senate also passes the Build Back Better Act, it will create the federal First Generation Downpayment Fund, which would provide down payment assistance to first-generation, first-time home buyers earning no more than 120 percent of the median income where they live. Qualified applicants are eligible to receive up to $20,000 or 10 percent of the home price, whichever is higher, to put toward a down payment. The legislation defines a first-generation home buyer as someone whose parents or guardians do not currently own a home or, if no longer living, did not own a home at the time of their deaths.

According to research from Urban Institute, about 4.4 million Americans would qualify based on the criteria of being renters whose parents haven’t owned a home in the past three years (a real estate industry definition for first time homebuyers). Of those 4.4 million, 1.58 million are Black, 1.22 million are Latino and 1.32 million are white.

The bill does not say exactly how the program could be used to target racial disparities. But it does specify that when funding is distributed to states to grant out, “racial disparities in homeownership” will be one factor among several that determines how much money each state will get.

A fragmented homeownership history

America’s racial homeownership gap was crystallized by the post-war home building boom that birthed the modern housing market nearly a century ago. After World War II, members of the rising middle class bought their first homes with federally backed low-interest loans. Later, they were able to draw on the equity of those homes to help their grown children afford the down payment on their own first homes. Those children, in turn, used their home equity to help out the next generation, and so forth. Through this process, families built a comfortable cushion of generational wealth.

But Black Americans and other communities of color were mostly locked out of that process. Money lenders rejected them, realtors shunned them and sellers refused to entertain their offers. This wall of discrimination contributed to a racial wealth gap that persists to this day. In 2016, the median white household had $171,000 of wealth, 10 times that of the $17,150 wealth of median Black households.

“The benefit of having a public policy around down payment assistance goes right to the fact that, for multiple generations, people of color were not provided the same access to homeownership opportunities,” says Janneke Ratcliffe, associate vice president of Urban Institute’s Housing Finance Policy Center.

In effect, federal down payment assistance would do for people of color what mothers and fathers have been doing for more privileged buyers for decades. A 2019 survey by the National Association of Realtors found that 32 percent of first-time homebuyers received a gift or loan from family or friends to help with the down payment. Parents without accumulated wealth or home equity to draw from can’t be the Bank of Mom and Dad for their home-buying children. But the federal government can play a similar role.

The fund created by the Build Back Better Act would be this country’s first national program, placing the U.S. alongside at least five other nations offering countrywide down payment assistance: England, Ireland, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Modeling other countries’ success

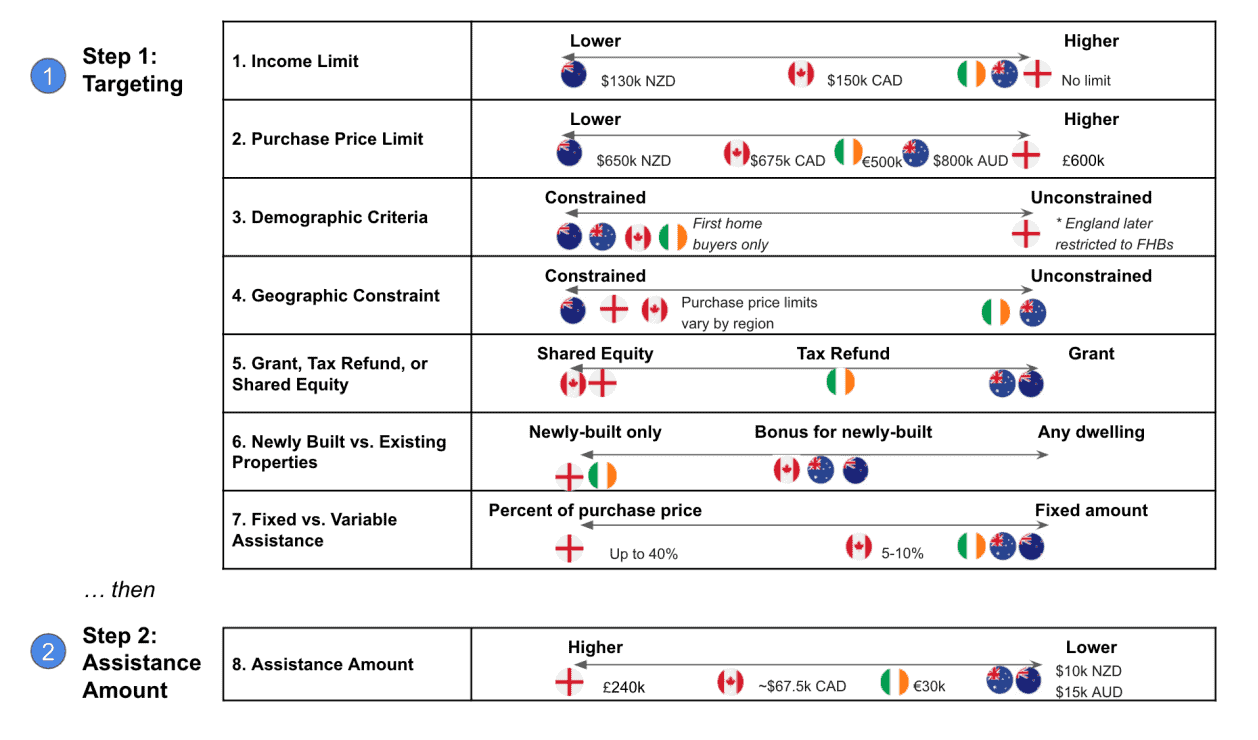

A newly published paper from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies analyzes those five national down payment programs to draw lessons on what the U.S. program should and shouldn’t do.

The paper was authored by Benjamin Ward, who recently received his masters from Harvard’s Goldman School of Public Policy. He says his interest in down payment as public policy comes from seeing many of his friends and peers, even those earning fairly high wages, struggling to purchase homes unless they got money from their parents.

“I’m concerned we’re heading down this path of where your ability to buy a home is contingent on your parents owning a home,” Ward says. “That’s a fast track to feudal society where there’s a land-owning class and a non-land-owning class, and whatever class you’re born into depends on your life chances.”

One key lesson from other countries’ down payment programs is that financial institutions and homebuyers are more likely to participate in a uniform, widespread program than one that’s tightly tailored to a specific region. In Australia, where Ward is from, the nationwide First Home Owner Grant provides some variation in grant size by state. But the eligibility requirements are simple and uniform countrywide. Banks are very comfortable with the program and fill out the paperwork for home buyers as part of the loan process. As a result, more than 80 percent of first-time home buyers receive the grant.

“There are different needs and costs in different housing markets in the U.S.,” says Ward.

“You definitely need some level of variation. But if things like eligibility criteria and reporting requirements and application processes become fragmented across states and local jurisdictions, I don’t see that as a very fundamental change in the current set up other than pumping more money into the system.”

The varied success of other countries’ programs show that the U.S. needs to strike a balance between targeting the program tightly enough that it serves those who most need assistance and ensuring there’s enough participation to create ongoing political support.

For instance, England’s down payment assistance program has no income limits and is open to both first-time and repeat homebuyers. The government does attempt to target funds to those who need it by taking a share of the value if the home is later sold and by collecting interest on the home’s equity. Those who don’t need assistance are less likely to want to share their home’s equity, and therefore less likely to seek out the funding. Nonetheless, thanks to the broad eligibility, 63 percent of participants in England’s program could have purchased a home without the assistance.

Critics of both the proposed U.S. program and the ones in other countries fear that down payment assistance can actually exacerbate housing affordability by increasing demand without increasing supply. Ireland, England and Australia attempt to address inflation concerns by limiting down payment assistance to home buyers purchasing new homes. In New Zealand, first-time home buyers can get $5,000 towards a down payment on an existing home and $10,000 for new homes.

With $10 billion, the U.S. down payment assistance program could assist at least 500,000 people. It would likely help even more, since in many housing markets, buyers wouldn’t need the program’s maximum $20,000 down payment for their home.

“Five hundred thousand additional homeowners is a great step in the right direction,” says Ratcliffe. “Especially if it’s targeted in a way that really serves people who have been cut out of homeownership in the past.”