Everything at the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) is designed to make it less scary. The bright yellow walls feature pictures of adorable seal and lion cubs, an overweight corgi waddles over demanding to be pet, and a live band rocks out in the foyer to Tom Petty’s “I Won’t Back Down.” On the seventh floor, Jeffrey Gold’s tiny office is filled with colorful children’s drawings and — higher tech but just as whimsical — virtual reality headsets. “Do you want to try it on?” the psychologist tempts.

As soon as you put on the Oculus headset, you enter a comical neon green fortress. From all sides, plump, pink teddy bears bound towards you. You can direct the game simply by moving your head, and the bears giggle loudly every time you hit them virtually with a plush purple ball. It’s a lot of fun, even for grownups.

Gold developed “Bear Blast” for medical use in cooperation with the software company Applied VR. He uses it with his young patients, aged 10 to 21, while they get their blood drawn or their bandages changed. The Children’s Hospital, where Dr. Gold leads the BioBehavioral Pain Management Lab, has been pioneering virtual reality for acute pain management since 2004. Initially, the game developers had designed a world where the bears screamed “Ow!” and exploded when they got hit. “That’s not helpful when the goal is to soothe pain,” Gold half-jokes. “I might as well put the kids in front of ‘Grand Theft Auto.’”

Inside the world of Bear Blast

Pain is not an objective experience — context determines its intensity. We experience it more acutely when we’re tense, anxious, or overly focused on it. And while every parent knows that a child can be distracted by putting him or her in front of a screen, studies demonstrate that VR is significantly more effective for pain management, especially when the games are interactive. “We compared: When you distract kids with cartoons, picture books or videos, it works, too,” says Gold. “But VR is significantly more effective because our brain does not differentiate between a virtual and the real environment.”

Because of Covid restrictions, we weren’t able to interact with patients directly. Instead, Gold shows a video to demonstrate how VR makes painful procedures less traumatic: 12-year-old Anthony, in his Star Wars shirt and VR mask, enthusiastically thrusts his head into the air while a nurse prepares the IV to treat his neuromuscular disorder. (Since the kids need to keep their hands and bodies still for the treatment, the game was modified to be steered with head movements alone.) He whimpers quietly as the needle enters his arm, but as his mother confirms afterward, “No comparison to last time. Without VR, he screamed and cried.” Another patient, 15-year-old Ben, remains motionless when a nurse connects the port catheter to his boney chest for cancer therapy. He’s serene, and seems to be entirely immersed in “Bear Blast.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.With VR, Gold interrupts the cycle of fear and tension that intensifies pain. “If you are having a fun time, your body is producing natural endorphins,” he says. “It is a neurochemical analgesic.” Several times, he says, his young patients asked when the procedure would finally start — in their obsession with the game, they hadn’t realized it was already over.

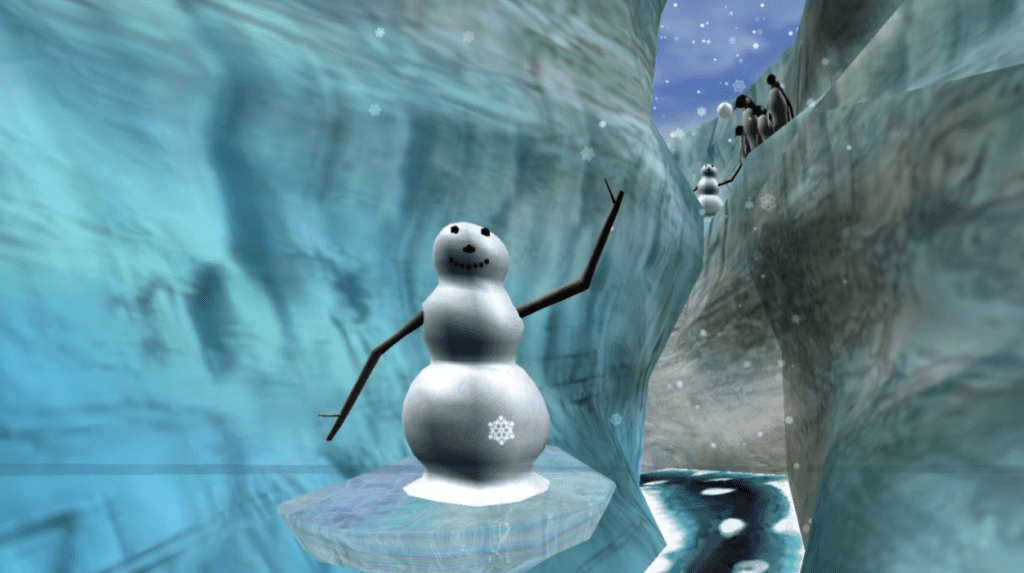

Virtual reality is increasingly being applied as a treatment for a variety of physical and mental conditions, from dementia to post-traumatic stress and phobias. In most of these areas, scientific evidence is slim. But its effectiveness in short-term pain management has been documented in a number of peer-reviewed studies. Psychologist Hunter Hoffman at the University of Washington in Seattle uses VR to mitigate excruciating bandage changes for his adult burn patients by immersing them in a game called “Snow World” filled with polar bears and icebergs. Studies show that these patients feel 35 to 50 percent less pain than other burn patients.

At the University Hospital in Heidelberg, Germany, patients wander through virtual natural landscapes, or they might take a virtual boat ride across a calm, picturesque lake. Michaela Wüsten, who’s in charge of the surgery ward, calls the use of VR “enormously successful. We have cancer patients who suffer from horrible pain despite pain medication. Some rate their pain levels three points less after a virtual tour. That’s a success we have not seen with any other method.”

And at Stanford University, Sam Rodriguez, a pediatric anesthesiologist who co-founded the Stanford Chariot program and the non-profit Invincikids, has shown that VR can reduce sedation in children undergoing minor surgical procedures. “Recovery times were significantly shorter in VR patients (18 vs. 65 minutes),” the study found, and the patients loved the experience. “Not only was the child less afraid and more cooperative, but, in some cases, removed the need for anesthesia altogether.”

Sixteen clinicians and academics, including Gold and Rodriguez, are now working together as the INOVATE-Pain consortium to provide guidance for best practices to manage pain with the help of VR and augmented reality.

When Gold started at the Saban Research Institute at CHLA, it was one of his colleagues, Dr. Skip Rizzo, and a graduate student, Dr. Greg Reger, an enthusiastic gamer, who came up with the idea to use games in the clinic. The student wrote his dissertation on the topic, and Gold began modifying VR sets with software developers for his patients.

In the time since, Gold says he has never observed adverse side effects. Adults sometimes experience vertigo, but children don’t because their middle ear is not fully developed yet. He also has an answer to the argument that teenagers already spend more than enough time in front of screens. “Our way of using VR short-term does not render patients dependent, like opioids,” Gold says. “Without a doubt, the kids are having a much better experience — no distress.” It is simply a way of using VR to focus the brain on something other than pain. “Instead of reaching for your pill, reach for your headset.”

For instance, he has successfully used an interactive Disney game with a female doctor of color, Doc McStuffins, to ease kids’ fears about upcoming procedures. They can direct Doc McStuffins to take blood pressure, suture a wound, or listen to a heartbeat. “She’s a good role model for children, and also helping them to manage their distress before a procedure. It’s a win-win-win.” Another game, Ready Teddy, teaches little kids to hold still in the MRI machine, eliminating the need for sedation. “A lot of our kids go through many procedures annually, so they might be exposed to sedation many, many times. This program can eliminate that.” Gold also wants to introduce multiplayer sets, “so the entire family or several patients can play together because the community is important in the hospital.”

The success of VR with long-term pain or trauma is less evident. “Chronic pain has a lot of variables; and each trauma, each pain experience is different,” Gold acknowledges. “Maybe there will never be one method that works for everybody equally.”

But for short-term pain, the data is convincing. At CHLA, Gold has extended the use of VR to IV catheter placement and painful gastroenterological procedures. Gold has also started to use Augmented Reality. The advantage of AR versus VR is that one still sees the real environment but enriched by virtual elements. “This is important for procedures where we need to see the patient’s eyes, for instance for anesthesia, we need to see when the kids fall asleep,” Gold explains.

Gold explains that “the game intensity needs to match the pain intensity.” He shows me one that starts with the player choosing a cartoon face to indicate pain level, from a smiling one for zero pain, up to ten, a face twisted with pain. I try level four. Immediately, dice, cones and pyramids race toward me. With a virtual gavel, I whack them into pieces. Gold shows me a video of a teenage boy who’s wheeled into the operating room with the game control in his hands, smiling and totally immersed. “You can see the nurses are all laughing, and the surgical techs think it’s hysterical because the kid is so into it.” This is markedly different from the nurses’ usual experience “when the kids can be tense, struggling, crying, angry and afraid.”

For the doctor, the use of AR and VR goes far beyond entertainment: Eliminating stress and anxiety before the surgery may lead to better postoperative outcomes. “They fall asleep laughing and giggling,” Gold says, “and then they wake up from the surgery just as relaxed.”