After establishing the world’s biggest online platform for long-distance carpooling, BlaBlaCar, in Germany, Christian Schiller took a year off to travel around the world. He was sailing between Colombia and Panama when the boat hit a garbage patch several hundred meters long. “When the rudder got stuck in the plastic trash in the Caribbean, I thought back to my time in Houston, Texas, where I had done an internship as a Fulbright Scholar with one of the biggest international construction companies,” he says via Zoom from his Hamburg office, shaking his head. “In Texas, I had seen the crazy effort we need to extract oil from under the earth. Then we use it once and it ends up in the ocean. I can hardly imagine a bigger waste of value.”

When he got back to Germany in the summer of 2018, he didn’t have a job lined up and started reflecting: What am I really passionate about? Where can I make the biggest difference with my background as a digital platform builder?

At an innovator conference in Berlin, he met software engineer Volkan Bilici who had worked as a software developer for plastic manufacturers. Together, they started Cirplus in the final months of 2018, an online platform designed to solve one of the most vexing problems this planet currently has: the plastic crisis. The company name for the world’s first global recycling platform for plastic is a wordplay, meant to indicate both the need to move to a circular economy and the outsized value of plastic. “This motivates me to this day,” Schiller says, “how wasteful humankind treats this incredibly valuable substance.”

Crushed by negative news?

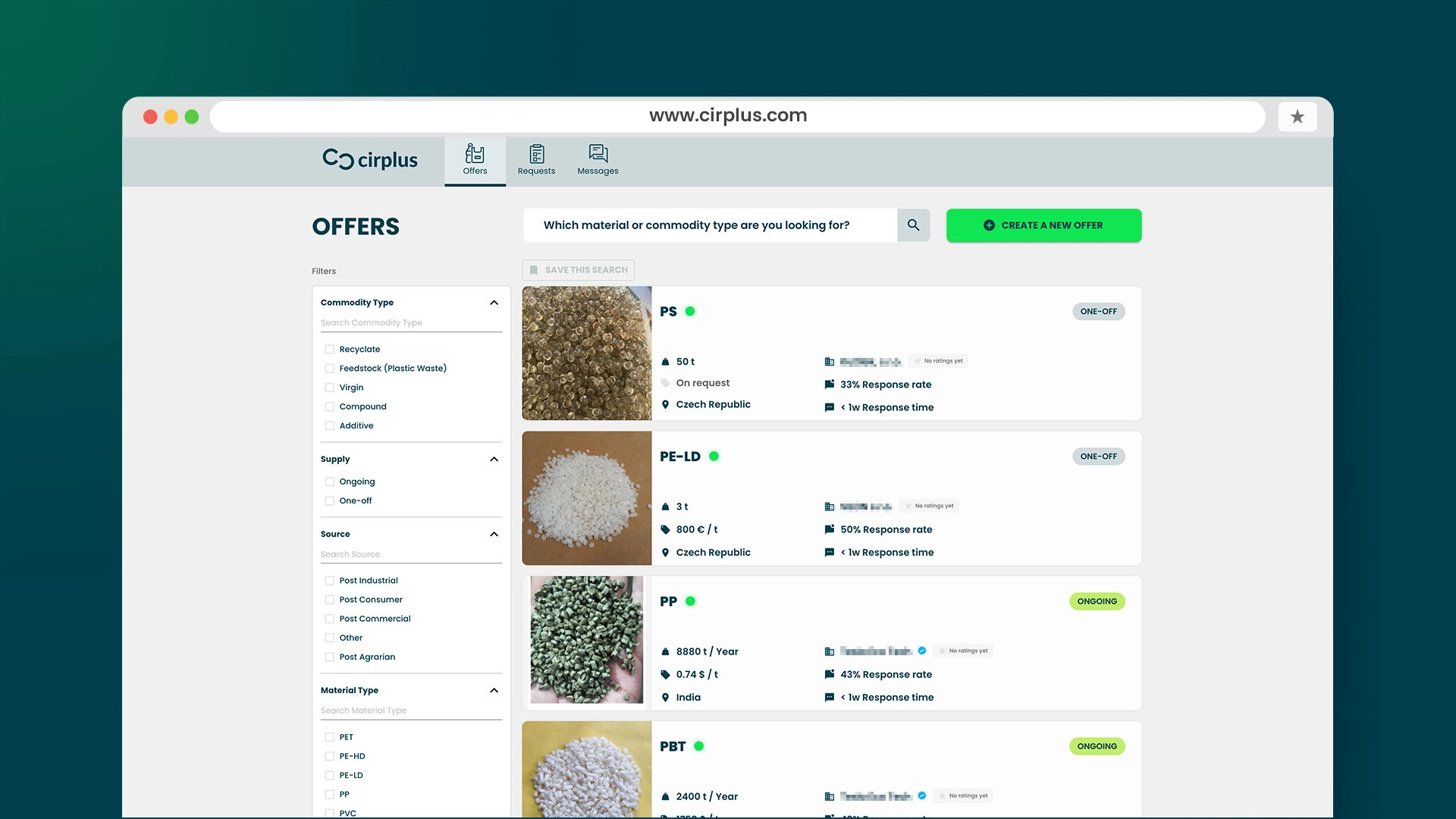

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.Schiller’s idea seems simple: connect recycling companies with manufacturers and distributors to close the loop. Currently, the low level of digitalization and the opaque market for different kinds of plastics make it difficult to even get an overview of the available material. Cirplus uses its own software to follow the material across the globe and create transparency for buyers and sellers of recyclates — think post-consumer shampoo bottles, caps and more. Once broken down, they can be used to make new products. The platform — which Schiller hopes will one day be the Amazon for recycled plastic — currently has 2,500 users, including packaging giants that handle big labels.

But speaking with Schiller makes it obvious that Cirplus is only one piece of the puzzle in the complex process of handling our trash crisis. Despite recent advances in local and national laws, with entire countries such as India and the EU banning single-use plastics, plastics production continues to grow. “By 2050, plastic production is estimated to hit more than one billion tons per year,” Schiller says. With the amount of plastic grows the amount of plastic trash — currently 240 million metric tons per year, according to the World Bank. Barely five percent gets recycled, and the US tops the world at 287 pounds of plastic waste per person per year, according to a 2020 estimate.

Plastic is one of the most difficult materials to recycle because of its various components, but reducing and recycling the material is also one of the most urgent. The recent train disaster in East Palestine, Ohio, raised public awareness about the often highly toxic additives involved in plastic manufacturing. Schiller was perplexed after starting Cirplus when plastic manufacturers openly admitted to him that they didn’t know where their plastic trash ended up.

“They told me, ‘To be honest, we weren’t forced to bother with that,’” he says. “It’s actually pretty shocking: In Europe, we don’t know what happens to eight to 15 million tons of plastic trash.” But we do know that at least 14 million tons of plastic end up in the oceans every year.

New legislation aims to change that: Starting in 2030, the EU will force companies to use a percentage of recycled plastic in their manufacturing, not just virgin plastic. “It is really unfair that the industry was allowed to keep the profits while passing on the environmental costs to everybody else,” Schiller comments. (Exxon, the world’s largest producer of virgin polymer derived from petrochemicals, just announced a record $56 billion in earnings for last year.)

Schiller once studied law and international relations with the goal of becoming a career diplomat, but an internship in the German embassy in Washington, DC made it clear to him that bureaucracy was not his strong suit. In a way, he’s now becoming a global diplomat for plastic recycling.

Recycling plastic is fiendishly complex. Many people think the plastic we put in the recycling bins will be recycled. The EU officially claims a recycling rate of 13 to 15 percent for plastic but recent reporting unmasked the truth. “When you take out the PET bottles that have a higher recycling rate because of the deposit system, you end up with less than five percent of plastic recycling,” Schiller acknowledges.

One issue is the web of local recycling options that might differ from one city or community to the next. The EU alone has 27 different recycling laws. Another are the often toxic additives plus contaminants in post-consumer plastic. And even after this is dealt with, melting down plastic components creates a stink that is hard to mask.

“Which problem are we actually solving?” Schiller therefore asks. “The lack of transparency of trash and recycling streams is one of the biggest.” Without a global platform, a manufacturer in, let’s say, Belgium, doesn’t know where he can buy a ton of plastic recyclates while a plastic waste collector in East Europe is sitting on a ton of recyclates. “The buyers at the big labels such as Procter & Gamble, Henkel or Beiersdorf need to reliably secure recycled plastic in a consistent quality before they seriously transition from virgin plastic to recycled plastic,” Schiller says.

Currently, virgin plastic is 20 to 30 percent cheaper than recycled plastic, and he says that he hears from manufacturers: “‘We don’t have the buy-in from our CEO to buy the material for 20 percent more. Talk to me again in a year.’” Others want to include recyclates, “but reliability in quality and quantity is essential. It is simply more difficult to achieve the exact color blue a brand might be known for from recyclates.” Second, he says, nobody wants to deal with 300 different recyclers. “The big producers have three to five big suppliers where they order a million tons of plastic for the next year.” Also, he notes, “This is an industry that still relies on fax machines and phone calls. It needs a major investment in digitalization.” As long as recycling is more expensive than virgin plastics, few invest in innovative recycling methods. “If you really want to move to a circular economy, you have to look at the recycling market like we currently view the energy market,” Schiller says.

Cirplus is still a small startup with only 12 employees, based in Hamburg. However, the platform has offered up to 1.3 million tons of available plastic. Cirplus and its competitors such as Plastship are emulating Metalshub, a rapidly expanding digital platform to trade metals, started in Düsseldorf, Germany, in 2016 that has moved $3 billion worth of material. How much material was actually traded through Cirplus is unknown to Schiller because until recently, companies could look up suppliers and then cut a deal outside the platform. A relaunch this April will change the business model of Cirplus and prompt clients to trade on the platform itself. Schiller expects that the platform will truly take off when the 2030 legislation approaches. “Manufacturers still tell us, they are opting for the cheapest, easiest option, which is virgin plastic, and they will only pivot to recyclates when they are forced to by either the laws or consumer pressure.”

To really solve the plastics crisis, Schiller pushes for bold and big moves. In 2022, he was instrumental in establishing a new standard for plastic recyclates, DIN SPEC 91446, to streamline recycling. He points to Sweden, where a plastic recycler is currently building the world’s largest plastic recycling facility, Site Zero, with the ability to handle 200,000 tons of plastic packaging every year once completed later this year. Norway is recycling 97 percent of its plastic bottles and is leading the negotiations to hammer out an international UN treaty to reduce plastic pollution, similar to the 2015 Paris climate accord.

Until then, Schiller advocates for the classic “3 Rs” mantra for the move to a truly circular economy: reduce, reuse, recycle.

He sees himself as an “activist-entrepreneur,” meaning his platform is as much about solving the problem as raising awareness about the multifold aspects of the crisis.

Last summer, he visited the world’s largest landfill in Jakarta, Indonesia, which absorbs more than 7,000 tons of waste daily. Hundreds of waste pickers sort through the stinking trash, searching for valuable metals. For years, they overlooked plastic, but the Plastic Bank with its “social plastic” program has created new incentives for locals to collect and process ocean-bound plastic. The program claims to have diverted more than 1.5 billion plastic bottles from the ocean.

Every recycled pound is a pound less of plastic in landfills or oceans.