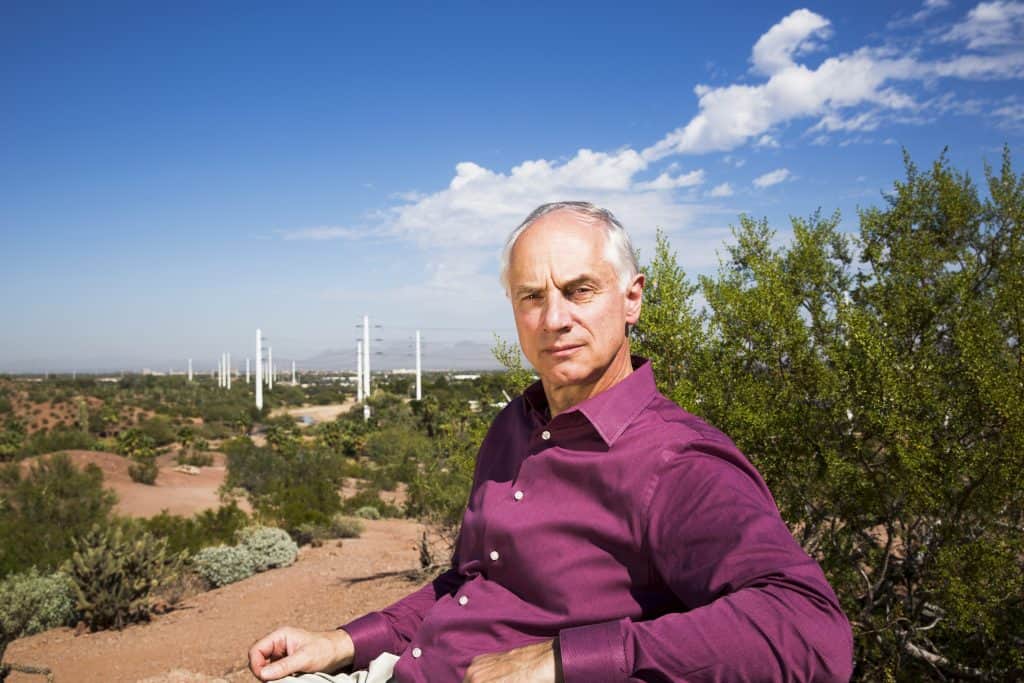

Klaus Lackner’s lab at Arizona State University looks as if an artificial Christmas tree exploded. Seemingly every surface is covered by white shreds of material, some small, some large, some slim, some thick. They look like plastic, but have the feel of stiff leather. And they are, according to Lackner, the head of the university’s Center for Negative Carbon Emissions, our best hope for avoiding catastrophic climate change.

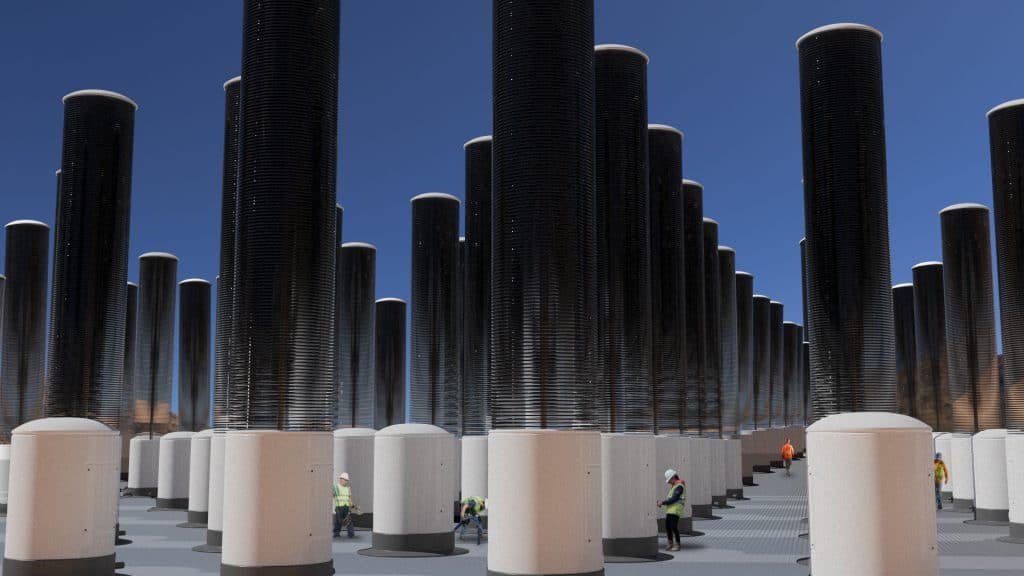

Lackner’s resin strips absorb carbon dioxide when they’re dry and release it when they’re wet. In cooperation with the Dublin-based company Carbon Collect and his colleagues at Arizona State, he wants to build an artificial forest in the desert: 1,200 CO2-eating columns, each up to 30 feet tall, that could capture 100 tons of carbon dioxide per day — the equivalent of sucking up the emissions of about 8,000 cars. The white shreds will form the leaves of the “mechanical trees,” passively absorbing CO2 as the wind passes through them.

The plan only seems radical until you consider the alternative. “The CO2 emissions that are already in the atmosphere make it increasingly unlikely that we will stay under two degrees Celsius of global warming,” the soft-spoken German physicist says. “It’s not a problem that will go away on its own. Therefore the capturing and storing of CO2 is unavoidable. It is too late now to argue whether we need to eliminate CO2 or not. We must get it out of the atmosphere.”

Of course, carbon-absorbing machines were invented millions of years ago. They’re called trees and plants, and they exist throughout the world. So why not simply plant more of them?

“The resin binds CO2 more efficiently than any other material,” says Lackner. “Each column is 1,000 times more efficient than a tree.” Wind speed determines exactly how much CO2 the resin binds. Once it is saturated with CO2, which takes about 30 minutes, the columns fold like an accordion into water, where the CO2 is washed off for storage or reuse. Then the process begins again.

“We use almost no energy; the columns stand in the wind just like a tree,” says Lackner. “Unlike other methods, we need no ventilators, no propellers. Because we need only water, we are ten times cheaper than comparable techniques.” As a result, he hopes to use the captured CO2 to produce fuel at a competitive price. Lackner and Carbon Collect will build the first columns this year at the campus of Arizona State’s Global Futures Laboratory in Tempe.

In 1999, Lackner became the world’s first scientist to suggest CO2 could be captured from the air to manage its climate impact. For many years, he had to explain why capturing carbon was even necessary. Now the consensus among scientists and engineers is that not only is it necessary, it’s mission critical.

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change relies on carbon capturing to keep global warming under two degrees Celsius. If we hit three degrees, we’ll lose most coastal cities. At four degrees, most of Europe will be permanently drought-stricken. In 2020, the International Energy Agency urged governments and companies to focus on developing technologies for carbon capture, utilization and storage or international climate targets will be “virtually impossible” to reach.

“Even if we stopped emitting CO2, the problem won’t automatically go away,” says Lackner. “Too much CO2 is already in the atmosphere. It can last for thousands of years, and it is our responsibility to clean it up. Nature itself cleans up, too, but too slowly, and we can’t wait that long.” He emphasizes that renewable energies are the solution for the future. “But the transition takes time. Until we’ve made the switch, the CO2 will be so high that we have no choice but to lower it.”

From a technical standpoint, solutions are challenging because though atmospheric CO2 increased by 50 percent in the last 150 years, it still makes up a mere 0.04 percent of the air. In other words, if we compared air molecules to rice in a bowl, only one of every 2,500 grains of rice would be CO2.

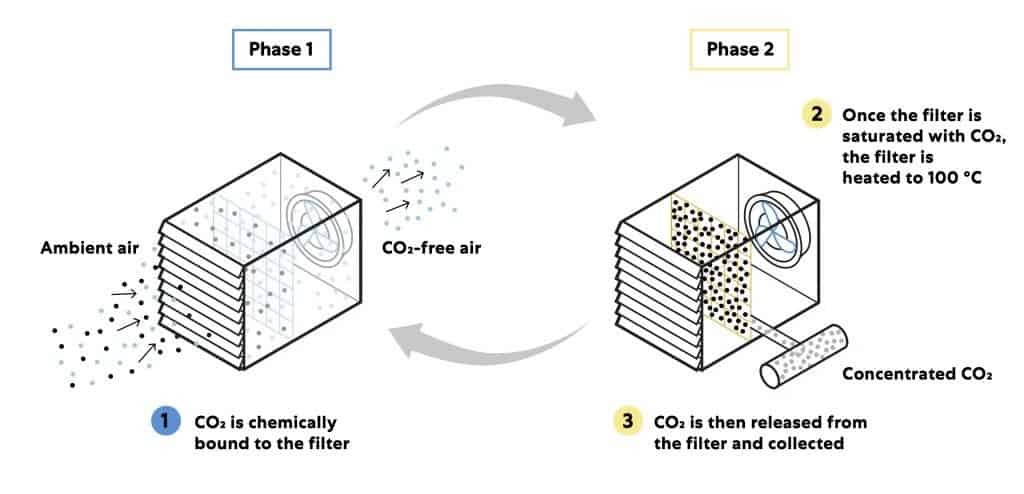

But the absorption of the trace gas is possible, as other innovators have proven. This month, the Swiss company Climeworks opened “Orca,” the world’s biggest direct air capture (DAC) plant in Iceland, that will pump about 4,000 tons of captured CO2 underground per year, where it will be converted into stone by the Icelandic company Carbfix.

And a Canadian company called Carbon Engineering captures about a ton per day in British Columbia, absorbing the CO2 in liquid and then storing or converting it into fuel by adding hydrogen. The company is preparing to engineer an even larger DAC plant in the Permian Basin with the potential to capture one million tons of CO2 each year. “Eventually, we will build a plant that does the work of 40 million trees,” Carbon Engineering CEO Steve Oldham predicts.

So, the technology exists, but at what cost? Climeworks charges between $600 and $1,000 per metric ton. Lackner refuses to attach a price tag to his artificial forest, not least because the exact costs are still being calculated. In the scientific journal Joule, Carbon Engineering founder David Keith wrote that his company will eventually be able to capture CO2 for less than $100 per ton. That’s still too expensive, Lackner knows. “These technologies are still very new and will improve drastically over the next ten years. We are at the stage where car makers were when they developed the first prototype of a car. It drove, but it’s no comparison to the cars we have today. The same holds true for DAC.”

Lackner is convinced the cost of carbon capturing will continue to decrease. “The first solar photovoltaic panels were extremely expensive, too. Now they are being mass-produced and are affordable. The more complicated question is: Who will pay for the CO2 that’s already in the atmosphere?”

Lackner sees two paths to financing the technology: One is to simply treat carbon capture like trash removal. “If I throw my trash on the street, you’ll complain. If I say, it’s 20 percent less trash than last year, you still won’t be happy. In a climate context, we have produced so much trash that we simply have to clean it up. When mankind takes a ton of CO2 out of the earth, we also have to clean up a ton of CO2. It’s that simple.”

Companies are already investing substantial amounts in the technology as part of their carbon offset. The likes of reinsurance giant Swiss Re, Microsoft, Audi, Shopify and Stripe have invested a total of more than $100 million in Climeworks. In return, Climeworks promises to certify the stonification of a certain tonnage of CO2 for them — for instance, 1,000 tons for Audi by 2023, an amount equal to planting 80,000 trees. Coca-Cola is buying CO2 for its sodas from Climeworks, and Climeworks is also offering a carbon offset “subscription” to individuals starting at eight dollars per month. Bill Gates is one of Carbon Engineering’s investors and Climeworks’ biggest client. But all these efforts are still a drop in the bucket compared to the 40 billion tons we are emitting globally.

The second big question is what to do with the captured CO2. Store it underground, like Ireland and Iceland are proposing? Use it as fertilizer for greenhouses, as the Swiss Climeworks plant does?

New uses for captured carbon are proliferating fast: bridges can be built with carbon fibers instead of cement, and cosmetics can be made of algae fertilized with CO2, as Lackner is doing.

On a larger scale, both Lackner and Keith see the most potential in transforming CO2 into fuel. “To have an effect worldwide, we need to talk about gigatons, not megatons. The only method to use vast amounts of CO2 is fuel,” Lackner says. “We need to stop extracting oil, coal and gas, but we still need fuel. When we use solar or wind energy to convert CO2 into new fuel, we have carbon-neutral fuel.” Of course, the CO2 will be released back into the atmosphere when it’s burned, but because it is effectively recycled CO2 it’s carbon-neutral.

Carbon Engineering optimized the existing process of converting CO2 into fuel, and CEO Steve Oldham says that the company now has a marketable product: climate-neutral fuel without oil drilling.

“At the cost of $100 per ton CO2, gas prices rise about one dollar per gallon,” Lackner calculates. “When we get the cost down to $30 per ton CO2, the cost for gas only rises 20 cents. Oil prices go up and down more than that. That’s a pricing area we don’t have to argue about anymore.”

Lackner is convinced that CO2 removal will become “a giant industry, bigger than the oil industry to the tune of $1 trillion per year.” He compares the current discussion to the debate about sewage 150 years ago. “Once people understood that sewage causes cholera, sewage and trash removal became a no-brainer. It’s the same here. But how much damage are we willing to accept before we act?”