This story was originally published by Next City.

So many things could have gone wrong with the vacant storefront at the historic former Ferdinand Furniture store building in Boston’s predominantly-Black Roxbury neighborhood.

Historically, a lot has already gone wrong in the area. Redlining — the pattern of racial discrimination in lending — allowed homes, apartment buildings and commercial buildings in Roxbury to decline. Redlining also means small businesses in the area have long had trouble accessing loans or other investment capital to grow. Racial discrimination in city contracting locked out many Roxbury businesses from the reliable income of a City Hall contract. Racial discrimination in hiring, wage-setting and promotions held back many of the area’s working age adults in the job market — not to mention the disproportionate impact of mass incarceration on Black communities.

That pattern could have continued within the former Ferdinand Furniture storefront. The surrounding community could have been ignored or brought in to participate in endless community meetings to voice their dreams for the space, only to learn later it was all just for show and they were never taken seriously in the first place. A developer or real estate brokerage with zero ties to the community might have gone behind the community’s back to line up a tenant, based on whatever financial analysis determined to be the “highest and best use” for the space, community voices be damned.

The tenant coming in could have been a national restaurant chain, or a private equity-backed restaurant concept by a celebrity chef who’s never visited Roxbury before. Profits from the restaurant, generated in part out of the cultural cache of the location, might be sent thousands of miles away to a bank account held in an overseas tax haven.

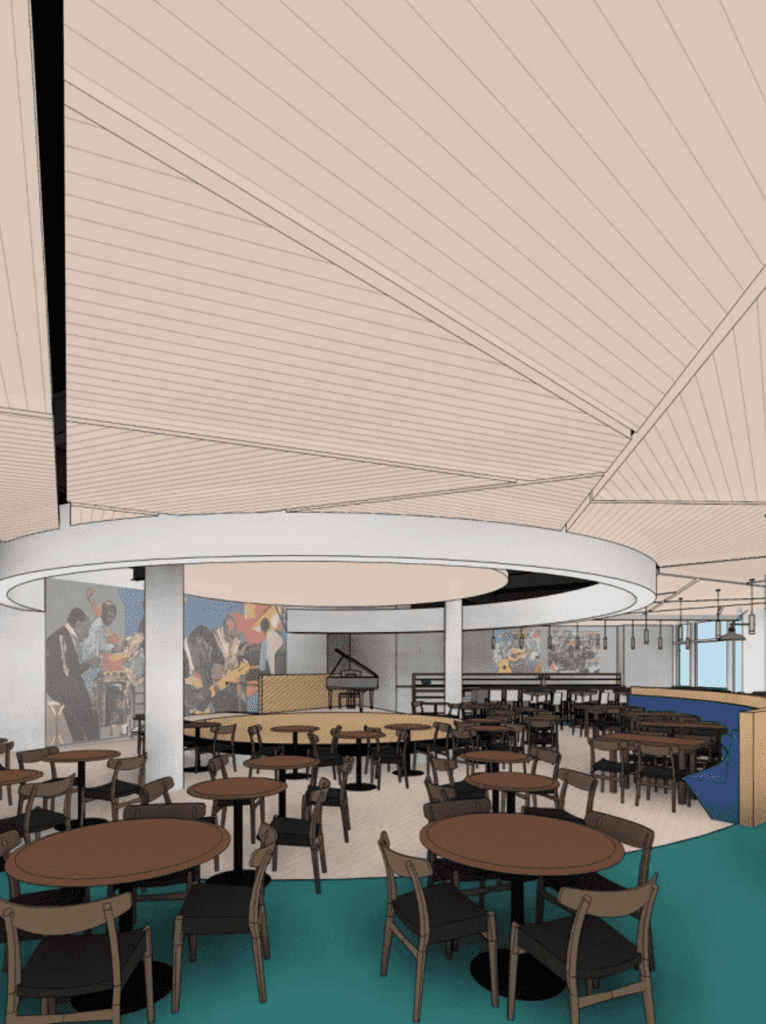

But instead of continuing that pattern, the former Ferdinand Furniture storefront will soon open its doors as the brand new Jazz Urbane Cafe, a sit-down restaurant and performing arts space that will feature local musicians and other artists. It’s the kind of cultural and community gathering space that residents in the area have dreamed of for years. The all-Black Jazz Urbane founders have deep ties to Roxbury.

What makes this project unique is that the community didn’t just say it wants Jazz Urbane; it voted to put some of its own wealth at risk for the business. Through the Boston Ujima Project, members of the surrounding community recently voted to approve a six-figure investment to make the community itself a part-owner of Jazz Urbane Cafe. So the community will also receive a share of the wealth generated if it all works out — on top of gaining a cultural landmark restaurant and performance space to showcase its artists and provide jobs for some of its residents. For Nia Grace, born and raised in Roxbury and part of the Jazz Urbane founding team, it’s a powerful moment.

“I always think about things kind of being full circle,” Grace says. “I did not have the privilege and honor to know what it looked like when the building was active. It was always something I just wondered about. It needed more investment, more love and more care. I love being able to come home and nurture something that was such a big part of my childhood.”

A history of disinvestment

It’s not just about the outcome. The process of how the community got here matters even more.

Too often in neighborhoods like Roxbury, disinvestment goes beyond the mere lack of capital; there’s also a mutual distrust between the neighborhood and mainstream institutions. These neighborhoods don’t trust the public or private sector to work for their benefit. Mainstream public or private sector institutions also often don’t trust members of these communities to provide worthwhile ideas for development projects.

Some disinvested communities have turned to making outside developers negotiate community benefit agreements promising jobs, housing or other benefits to communities surrounding major projects. But the track record of those agreements has been spotty at best. One of the most heralded early examples, the Kingsbridge National Ice Center in the Bronx, has yet to produce a single actual benefit and is now hanging in limbo as the project has completely stalled. After 10 years, the developers never successfully raised the needed funds to get started, and the city recently terminated the redevelopment contract with the developer group who signed the community benefit agreement.

Writing in Architects Newspaper about new city-backed development projects in Chicago’s historically disinvested neighborhoods, architectural critic Anjulie Rao says, “After decades of disinvestment instilled a sense of distrust, these neighborhoods don’t just need new developments — they need the city to lead reparative processes.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.A reparative process starts with recognizing that history of disinvestment, acknowledging it was intentional on the part of the public and private sector players who perpetrated it, that it was tied largely to racism, and that it is a painful history — but also more than a painful history. The people who lived in and still live in these neighborhoods have joyful memories of these places, too, and there are elements that help keep those joyful memories alive — like the former Ferdinand Furniture store facade, which loomed large over the Dudley Square intersection for decades even after the store closed in the 1970s. It was vacant, yes, but it was and remains a beautiful building.

Like many other young Black children growing up in Boston, Grace remembers going shopping with her mother on Saturday mornings in Dudley Square: at department stores, street vendors lining the sidewalks, or A Nubian Notion, a landmark family-owned convenience store and boutique. The area was once known as Boston’s “other downtown.” Dudley Square had an elevated rail station until 1987, and still has one of the largest bus stations in the city where more than a dozen bus routes connect.

“‘Going Down Dudley’ is what we used to call it,” Grace says. “[The Ferdinand Furniture building] was definitely a cornerstone of the neighborhood, but it looked shuttered.”

It hasn’t been a linear process to revitalize the former Ferdinand Furniture storefront, but there has been a common thread tying the pieces together: neighborhood, city and investors learning to trust each other as equal participants in the development process. The neighborhood had ideas and aspirations; the city took them seriously, and they inspired even a few outside investors to invest some of their dollars in line with those ideas.

Keeping the neighborhood involved

The redevelopment moved slowly, and it helped keep the neighborhood involved at every step. All the way back in 2006, then-Mayor Thomas Menino raised the idea of redeveloping Dudley Square, including the former Ferdinand Furniture building, according to Architects Newspaper.

The city already owned much of the property at the site, but the emerging designs led to the city acquiring two additional small buildings via eminent domain in 2011. The handful of small businesses didn’t like being displaced, but, as reported in the Bay State Banner, community-based organizations in the neighborhood supported the move even though they had their own painful memories of eminent domain being used to clear out large swaths of Black neighborhoods to clear a path for highways.

By 2015, the city had completed the new construction and the restoration of the historic facades at the site. According to general contractor Shawmut, 41 percent of construction workers for the project were Boston Residents and 44.9 percent were workers of color. The city moved its education department into the building, bringing hundreds of workers to the neighborhood daily.

The combined new and restored structure was renamed the Bruce C. Bolling Municipal Building, after the city’s first Black City Council president. A smaller cafe and other tenants moved into first-floor spaces, paying below-market rents as required by the building’s federal New Markets Tax Credit financing. But the former Ferdinand Furniture storefront remained vacant.

In the meantime, a group of residents from Roxbury and Boston’s other predominantly-Black neighborhoods Dorchester, Mattapan and Jamaica Plain began meeting regularly to talk about how to model a democratic economy, one that would respond to their needs. It came to be called the Boston Ujima Project — “ujima” being a Swahili word and one of the seven Kwanzaa principles, understood to mean “collective work and responsibility.”

Since its first general assembly in 2017, which Next City covered at the time, the Boston Ujima Project has spent much of its energy coming up with ways to telegraph to neighbors and to those outside their communities what they like in their neighborhoods, finding out what investments might be needed to maintain those things, and also determining what they would like to have in their neighborhoods in the future.

Privileged and credentialed technocrats might recognize all that as part of the work of urban planning. Ujima members have held neighborhood assemblies, citywide assemblies, and attended regular convenings held by other community organizing groups across the city to invite more residents of their communities to discuss, and ultimately vote on, investment plans for their neighborhoods.

Sit-down restaurants and performing arts spaces have come up frequently on top of the Boston Ujima Project wishlist. Roxbury residents had long been calling for performance spaces and sit-down restaurants in their once-booming Nubian Square. So it was no surprise to anyone when the city finally put out an RFP in 2017 for the 7,800 square-foot former Ferdinand Furniture storefront, calling for “a wide range of businesses including a restaurant, a major performance space or a meeting space.”

Musician turned owner

It was a pleasant surprise that the city’s economic development agency leadership was among the first to reach out to Bill Banfield to encourage him to submit a proposal for the former Ferdinand Furniture storefront.

A Detroit native, Banfield first moved to Boston in the 1980s, landing a job teaching music at Madison Park High School, just a few blocks from Dudley Square. An accomplished jazz producer, composer and guitarist in his own right, Banfield eventually took a page out of Motown founder Berry Gordy’s book and borrowed some cash from his parents to start his own recording label.

Banfield’s work took him away from Boston for a while, but he eventually returned to take a professor position at Boston’s world-famous Berklee College of Music. Around that time, in the late 2000s, he started collaborating with Nia Grace to reinvigorate the local jazz performance scene in Boston. They started at Darryl’s, where Grace was still just a manager. She acquired the restaurant in 2018.

While Darryl’s is technically in Roxbury, it’s at the very northern edge of the neighborhood. Banfield dreamed of something bigger to draw people to the commercial heart of historic Black Boston, now known as Nubian Square. The city officially renamed the square in 2019, a tribute to the broader notion of Nubia, a region of the African continent, being symbolic of the area’s Black heritage.

“Darryl’s had certainly been an important place, and there were other places but we didn’t have the kind of mainstream venue that, say, Scullers represented for Cambridge,” Banfield says. “Boston really needed it.”

The city awarded the space to Banfield and the Jazz Urbane Cafe concept in 2018. It also set up the restaurant venue with a performance-based lease — its rent payments are a percentage of monthly revenue. It’s not uncommon for private landlords with storefront spaces to make such agreements with commercial tenants, but no one had ever heard of the city government doing it.

“It was really the city thinking innovatively and realizing if you want homegrown businesses to occupy prime commercial space, they would need that kind of assistance, on the lease and in some other regards, as well,” says Turahn Dorsey, the third member of the Jazz Urbane founding team. “They saw the possibilities from the very beginning.”

Another transplant from Detroit and a former student of Banfield, Dorsey is also no stranger to city government, nor to the Bolling Municipal Building. He worked there from 2014 to 2018 during his tenure as chief of education for the City of Boston.

The neighborhood wants in

But even after securing the space, Jazz Urbane still needs to raise startup capital to finance its buildout and working capital to open its doors. In the middle of this process, the pandemic hit in 2020, putting everything on hold temporarily. As they’ve re-started the search for startup capital, the three founders made sure to come back to one of the first places they initially went to find investors — the Boston Ujima Project.

In addition to planning out some of the investments they’d like to see in their neighborhoods, the Boston Ujima Project also manages a small pool of investment capital to actually make some of those investments. Some of the funds come from community members in Roxbury, Dorchester and Mattapan, but the bulk of the dollars come from high-net-worth individuals and philanthropic institutions elsewhere in Boston and beyond. The voting members of Ujima, however, have the final say in making investments, and Ujima limits its voting power to members who are Boston residents identifying as working class and/or as a person of color, or a working class and/or person of color who has been displaced from the city. This setup flips the usual dynamic of the folks with the most money having the most power over investment dollars.

In April, after listening to the Jazz Urbane Cafe founders make their pitch, asking questions and reviewing the business plan, Ujima voting members approved a $200,000 investment to take a 3.29 percent ownership stake in the business. Also known as an equity investment, it is riskier than making a loan, but the potential payoff can be much higher. It’s the first equity investment for the Boston Ujima Project, and while it’s just a small ownership stake, there are larger implications.

Usually, this kind of early-stage equity investment is only accessible to people who are already wealthy — for example, the investors on the popular Shark Tank television series. But by pooling investment capital from multiple sources as a fund, Boston Ujima Project found a way to bring working-class communities of color as investors into an early-stage equity investment. And the Jazz Urbane Cafe founders want to provide an example for others from Black communities in Boston to follow, whether it’s through Ujima or other new channels for not-so-wealthy individuals or individuals of color to make early-stage equity investments in local businesses.

“They were among the first we went to – in part because we knew that we wanted strong representation by investors of color in Jazz Urbane Cafe,” Dorsey says. “Certainly other people will be welcome to the house, but we’ve long wanted something for ourselves and we’re not waiting for permission from traditional capital to do the things we’ve long wanted to do.”